Having just spent two weeks touring the west coast of the United States, one great pleasure has been visiting the various art museums to see some of the wonderful paintings which the immensely wealthy collectors of the late 19th- and early 20th-centuries acquired at a time when many of our country houses were in crisis. Sadly, in so many cases, the sales were a precursor to the complete loss of the house, with over 1,400 houses demolished since 1900. However, it is still possible to see a fragment of these grand homes as the demolitions fuelled an impressive transatlantic trade in architectural salvage which included entire rooms. The whereabouts of many of these are now unknown – but they do sometimes reappear in surprising places…

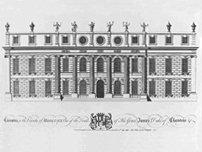

This post and the entire subject of country house architectural salvage owes an immense debt to the historian John Harris who has been chronicling these losses since he first started exploring country houses in the grim era following World War II. Of course, the trade had been going for many years: Nonsuch Palace, in Surrey, was deliberately sold for its materials in 1682, Cannons, in Middlesex, the seat of the Duke of Chandos was stripped and sold in 1747 after his death, and the once impressive Wanstead House, Essex, was similarly dismembered and sold to pay the debts of the spendthrift husband of the heiress in 1824. The plundering of rooms as part of the spoils of war by a conquering army has also happened throughout history with perhaps the most famous room taken also one of the greatest mysteries; no-one has seen the famed Amber Room from the Catherine Palace, just outside St Petersburg, since the German army meticulously removed it in 1941.

The country house room salvage trade takes off when, just as Europe is facing an agricultural slump which disproportionately affected landowners, the immensely wealthy industrial titans in the US were flexing their wallets to acquire collections which would become their legacies. In the UK, as the situation worsened, so the familiar pattern of contents sales started with pictures and other artworks being discreetly sold. Often many of these works were acquired by US collectors such as Frick, Mellon, Carnegie, Kress, amongst others, often on the enthusiastic encouragement of dealers such as Joseph Duveen. However, to display the art required the right setting, and so an industry grew up to satisfy a voracious demand for authentic rooms – even if the rooms weren’t identical by the time they arrived. Later, museums were also looking for rooms in which to provide context for their collections of furniture and art.

John Harris identifies the first stirrings of the transatlantic trade with the sale in 1876 of a supposedly ‘Jacobethan’ room to a Mrs Timothy Lawrence, which was incorporated into the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Harris next highlights the reference, in November 1897, in the sales/stock records of the famous Duveen family of art and antiques dealers of a ‘large Louis 14 Style Brown & Gold Room‘ ‘delivered free New York‘ for Mrs William C. Whitney which cost $10,000. By the early 1900s, adverts were appearing in Country Life magazine and the Connoisseur listing entire rooms or just the parts; chimneypieces being a popular offering. Building on the still lingering Victorian fashion for anything Elizabethan and Jacobean, dealers competed to offer the most choice rooms from the houses being demolished at the time. One of the largest dealers, Robersons, were boasting in 1906 of having ‘100 Old Marble Mantelpieces in Stock‘, whilst Druce & Co had 5,000 feet of old panelling. Books such Charles Latham’s ‘In English Homes‘ fuelled the fascination with these periods – perhaps even spurring on the demolition of some houses by creating a demand for the materials, and making it easier for the owners to decide to demolish. As the architect John Swarbrick, founder of the Ancient Monuments Society, argued in 1928, ‘history adds commercial value to buildings’.

This desire for ancient association led some dealers to be somewhat generous in their attributions of the architects or owners involved. The dealers Robersons were particularly apt at indulging in this type of misattribution, often assigning provenance with little or no research. Another firm, Gill & Reigate, were being quietly accused of fabricating rooms as early as 1926.

However, the finest pieces were often were those with a clear provenance, usually from a celebrated dispersal or demolition auction such as that of Cassiobury House near Watford or Hamilton Palace in Lanarkshire. The urban growth of Watford has spoiled the estate at Cassiobury and so it was gutted in 1922, leading to the sale and dispersal, via French & Co, of one of the finest sets of Grinling Gibbons carvings in the country, including the impressive staircase. Hamilton Palace, seats of the Dukes of Hamilton, was one of the most impressive houses in the country – and one of the greatest losses. Built on coal wealth, it was also its literal undermining with subsidence (but also it’s vast size) leading to its demolition following huge sales in 1919 which not only released huge quantities of art and antiques but also of material.

Although there were many buyers, the most voracious – and possibly indiscriminate – was William Randolph Hearst; publishing magnate and heir to a mining fortune which reputedly gave him an annual income of $15m. Although disliked by dealers for his lack of taste (something Joseph Duveen was particularly sensitive to), the value of his spending meant that they beat a path to his door despite his sometimes difficult behaviour. In one case, having bought the staircase from Hamilton Palace via French & Co, he returned it to them no less than three times – but as he had spent $8m with them they were willing to be indulgent. A network of agents throughout Europe sent him a daily stack of catalogues and flyers which he would eagerly read before dispatching orders for purchases. These would then be shipped to his five-storey warehouse which occupied a whole New York block and was dedicated to his acquisitions and employed a staff of 30. European purchases were mainly installed at San Simeon in California, but 50 English medieval salvages were installed at St Donat’s Castle in Wales which he bought without seeing and in which he only spent one night. In New York, he occupied five floors of a mansion block, creating a vast home which housed yet more salvage and art. Almost inevitably, Hearst’s spending caused financial difficulties leading to a badly timed sale of many items in 1941 through the Gimbel Brothers department store in New York – though much remains even today in that warehouse which is still owned by the Hearst Corporation, who sadly refuse access to researchers (and if anyone knows someone who can get me in there I would happily make the trip to New York!). The scale of Hearst’s acquisitiveness is astounding and I’ll probably revisit it later in a separate post.

Sadly, like a tide coming in, which swept so many items and rooms into houses and museums in the States, so it also retreated and they also were removed, sometimes to vanish, their present whereabouts unknown. Museums began quietly de-accessioning some rooms when they discovered that they perhaps weren’t as authentic and accurate as they had been led to believe. Sometimes it was a positive thing; that sense of place being the greater concern leading to restitutions such as the Inlaid Chamber from Sizergh Castle (now National Trust) which was removed to the V&A Museum in 1891 and returned in 1999. One rare success for a Hearst purchase was that of the Dining Room from Gwydir Castle in Wales which was returned – having never been unpacked – in 1996 (the story is wonderfully told in ‘Castles in the Air‘ written by the then owner).

Perhaps it’s a little harsh to call the rooms lost if they have only been moved but to take a room from its original context is to lose something of the intrinsic value of it as part of an architectural whole. That said, it could also be argued that they were being rescued as, when the houses were demolished, fittings which couldn’t be sold were sometimes burnt – John Harris recalls seeing a beautiful staircase from Burwell Park in Lincolnshire being put on a bonfire in 1957. Yet, so much of what was bought is still out there – particularly the items acquired by Hearst. Which leads me to my own personal discovery in a bar in San Francisco; if you are ever in the Fisherman’s Wharf area of San Francisco, do visit ‘Jack’s Bar‘ in The Cannery where you will be standing in the former Long Gallery of Albyns, an elegant Jacobean house built c.1587. It was demolished in 1954 but which had been gutted earlier with the gallery bought by Hearst but sold in the mid-1960s and given a new life – though not an elegant one.

So these rooms, once the centrepieces of some of our finest country houses, have been extracted and shipped around the world but particularly to America where, although they were initially often fully appreciated, now they may languish, unremarked and more worryingly unknown, vulnerable to just being dumped as though simple room decoration. So, if you know of a Hearst room installed in a house or museum (and I’d be particularly grateful to my many American readers) then please do post a comment or email me and we’ll try and make sure that these wonderful expressions of the craftsman’s art are not forgotten and lost forever.

—————————————————————————————–

If you would like to see some of the rooms and items then below is a small list of museums where these items are being exhibited (thanks to Andrew for help with the research):

New York – Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Tapestry Room from Croome Court, Worcestershire

- Dining Room – Kirtlington Park, Oxfordshire

- Dining Room by Robert Adam – Lansdowne House (a London townhouse)

- Staircase – Cassiobury House, Hertfordshire

- Drawing Room chimneypiece – Chesterfield House (London)

Philadelphia – Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Drawing Room / Dining Room / Reception Rooms from Sutton Scarsdale Hall, Derbyshire

- Drawing Room – Lansdowne House

- Panelled room – Wrightington Hall, Lancashire

Boston – Museum of Fine Arts

- Dining Room – Hamilton Palace, Lanarkshire

- Panelled room – Newland House, Gloucestershire

- Drawing Room – Woodcote Park, Surrey

Minneapolis – Institute of Arts

- ‘Tudor Room‘ – unconfirmed, possibly Higham Manor House, Suffolk

Louisville – J.B. Speed Art Museum

- ‘The English Room‘ – The Grange, Broadhembury, Devon

Amherst, Massachusetts – Mead Art Museum, Amherst College

- Rotherwas Room – Rotherwas, Herefordshire

Washington DC – Freer Gallery of Art

- Whistler Peacock Room – 49 Prince’s Gate, London

—————————————————————————————–

Find out more – some recommended further reading

- ‘Moving Rooms: The Trade in Architectural Salvages‘ – John Harris

- ‘No Voice from the Hall‘ – John Harris

- ‘Period Rooms in The Metropolitan Museum of Art‘ – Amelia Peck

I would imagine that getting complete rooms to fit their new homes must be a nightmare, involving bodging and butchery. Even Lutyens had trouble with New Place, Hampshire (1905/6) a vast house built specifically to accommodate early 17th century interiors from Bristol.

While on the subject of Wanstead House, Essex, there are walking tours of the demolished house’s grounds around the Temple, on Sat/Sun 17/18 September at 1pm and 3pm, as part of the London Open House weekend. There is also a guided walk on Saturday 17 September at 10am from Wanstead Station to The Temple, Wanstead Park, highlighting the ancient chestnuts, St Mary’s Church, a view of the Basin and Stable Block and other historical remnants of the Grade II listed historical landscape that formed the grounds of Wanstead House. It finishes at The Temple where walkers can find out more about the history of the rise and fall of this important Palladian mansion.

Please note that the London Open House website has been incorrectly showing this tour as being on Sunday on its Event Listings, which had not been updated as per the website’s Amendments list.

Nonsuch Mansion is also open for tours on Sat/Sun 17/18 September at 2pm-5pm, where you can also see the recently unveiled large-scale model of Henry VIII’s Nonsuch Palace in the Service Wing Museum.

Interesting, and worthwhile piece! Was Jack’s Bar at The Cannery previously a restaurant?

Yes, back in the 1970’s it was called The Ben Johnson restaurant. There may also be other period rooms in The Cannery, because between 1963, when Leonard Martin purchased the former Del Monte cannery, and 1966 when it opened as shops/bars/restaurants, he had purchased from Hearst’s New York warehouse a Jacobean staircase and two Elizabethan rooms, although it’s not clear whether these form the Albyns Long Gallery, or are additional rooms. There is also a 13th Century Moorish ceiling from the Palacio de Altamira in Toledo, Spain, on the 3rd floor.

For more about Hearst and his California estate now open to the public, see my March 4, 2011, post. I met Victoria Kastner, who has been the historian there at Hearst Castle for 30 years, and she might be able to give you more information about the New York City warehouse.

For not just a room, but an entire house see Agecroft Hall, now in Richmond Virginia:

http://www.agecrofthall.com/

There’s also Standish Hall, Lancashire, which after the death in 1920 of the last Standish family male, had its Tudor wing and chapel dismantled and sold to America by 1923, mistakenly as the birthplace of Myles Standish. I’m not sure where this ended up, anyone know? Individually sold oak panelled rooms (i.e. library, dining, drawing, state bedroom) appear to be in private collections.

I just came back from a similar trip covering both the east and west coasts of the US and was indeed impressed to find interiors in the MFA in Boston and some very interesting Federal (Bulfinch-designed) houses in Boston too – the Otis House and Nichols House. They are definitely worth visiting when in Boston, not least by way of comparison to contemporary English interiors, and I’ll be recording my visits during posts that will go live later in the year – http://visitinghousesandgardens.wordpress.com.

Otis House: http://www.historicnewengland.org/historic-properties/homes/otis-house/otis-house

Nichols House museum: http://www.nicholshousemuseum.org/

The third weekend in May is Open House in Boston, when different historic houses are open each year to visit – if I go back I’ll be trying to go then.

Armand Hammer’s home in DES Moines, Iowa has several Tudor room sets around which the home was constructed. It is off the beaten path but well worth a visit. A recent wonderful trip to Dumfries House revealed how many rooms, staircases and fire surrounds moved about the great houses within the UK. Some obviously travelled much further.

Please don’t forget that the Cranes, heirs to a plumbing fixtures fortune, installed the fittings from the library at Cassiobury in their splendid Georgian house of 1929, designed by David Adler at Ipswich, Massachusetts, and that it can be seen there on open days.

Thanks downeastdilettante – the Cassiobury library fittings included the overmantel carved by the famous, and brilliant, Grinling Gibbons whose work can also be seen at Hampton Court Palace. More information on the Cranes’ house is available for anyone lucky enough to be in the area: Castle Hill, Ma.

Cassiobury rooms seem to get around, with the Edward-Dean Museum in Cherry Valley, California, having 4 Grinling Gibbons wall carvings installed in 1958 in its Pine Room, from the original 7 formerly in William Randolph Hearst’s Dining Room at Ocean House, Santa Monica, California from 1929. The other 3 appear to be in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, perhaps being those originally lent by Marion Davies. There’re probably a bit like religious relics in churches, in that if a saint’s bones were all added together, they would make more than one full skeleton!

In Memphis, Tennessee, the Graham-Kent mansion has a linenfold chamber from the 17th Century that at one time was donated to Old Miss, the University of Mississippi, never used and finally sold back to the present owner of the house. It has been reinstalled. Robert Dechert, lawyer and book collector, installed similar wainscoting in his house at Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania. After his death, his books and the panelling was given to the University of Pennsylvsania in Philadelphia. Dechert bought the room from A.S.W. Rosenbach, the famous rare book dealer. Duveen Brothers also sold period rooms to builders of Long Island mansions.

Ahem ! Yes. The arrangements for restoring the room at Gwydir Castle were indeed successful and a lot of work since some of the packing had become misconstrued and required the Corbetts to go through the process of matching up misplaced- albeit numbered- placements. Reading all of that made my head swim. They did every bit of the work, as well. Whew ! Not to mention that the cost of retrieving all of it was actually out of their ballpark- cost-wise. Nonetheless, they achieved it and they deserve our applause. I just wish that the Metropolitan Museum could see fit to reimburse them since they were restoring the room to its rightful place. I wish them all the best and look forward to seeing the whole castle. If God made earth angels they are a prime example.

The Castle Lady

I’ve just been reading the John Harris book and it’s a fascinating story that doesn’t get told at all. You can see a slight part of something similar at Barrington Court in Somerset, where either a Tate or a Lyle (I always forget which) leased the house from the NT in the 1920s and ‘restored’ a lot of panelling from goodness only knows where.

Do you know of any other rooms of this kind in the UK, that aren’t in museums?

I’m wondering if any British rooms ended up in the enormous Lynnewood Hall in Pennsylvania, inspired by Prior Park in Bath and built by 1900 for Peter Widener, but with most of its statuary and interior rooms (e.g. mantels and walnut panelling) sold by 1993 by Carl Mclntire’s Faith Theological Seminary, who had purchased Lynnewood in 1952. Also, in 1940, Joseph Widener had donated over 2,000 sculptures, paintings, decorative art, and porcelains to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., with other furnishings auctioned around the late 1940s. There doesn’t seem to be any mention of Lynnewood in the Moving Rooms book, nor of another interesting mansion, Inisfada in New York, built by 1920 for Nicholas Brady, with some of its interiors auctioned in 1937.

There is one of the Hearst rooms that is now here in Dallas

https://www.papercitymag.com/home-design/joseph-minton-house-preston-road-highland-park-lost-english-house/#127883