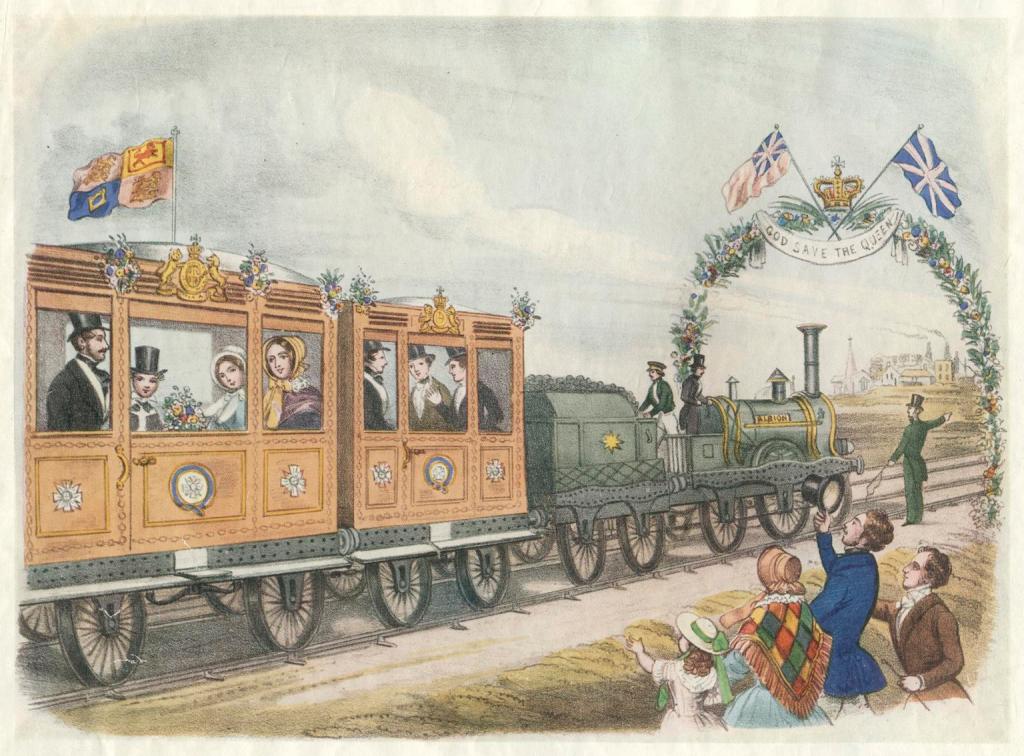

In September 1872, Queen Victoria was invited to stay at Dunrobin Castle in Scotland, seat of the Dukes of Sutherland. She naturally travelled by train, having used them for long-distance journeys since 1842. After being met by crowds at Inverness, her train left on the final leg in the late afternoon.

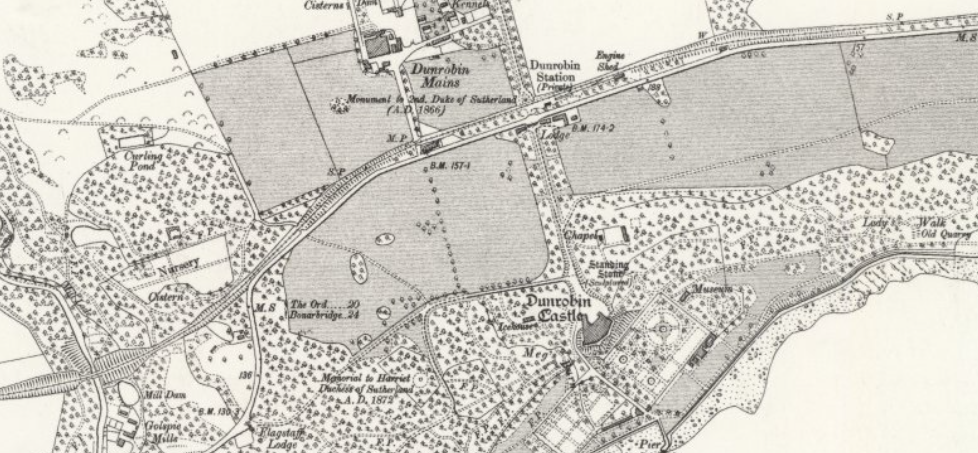

Just after passing the head of the Cromartie Firth, her afternoon tea was unexpectedly interrupted as the train stopped at Bonar Bridge station. Here, she records in her diary, ‘the Duke of Sutherland came to the door in such a curious get up, that I did not at first recognize him. He had been driving the engine since Inverness, but only appeared now on account of this being the boundary of the Sutherland railway.‘. The Sutherland being a private railway line which the Duke had conceived, financed and now enjoyed the privilege of running across his lands.

Such power and enthusiasm, stoked by immense wealth, were often the hallmarks of the development of the Victorian railway network. With it came the curious demands of landowners and aristocracy for the network to accommodate their personal needs, with the provision of not only private waiting rooms, platforms, and stations, but also entire railway lines.

Across the network, private train stations served royalty, aristocracy, industry, and the military. The control and influence of the landowners had an immense effect on the overall development of the railways, arguably more so than any other interest group. In the 1830s, the aristocracy were almost all opposed to the railways but attitudes changed as opportunities arose, resulting in the widespread granting of privileged access and rights to the railways.

This foundation for this article is based on research by others but focuses on the landowners and significantly expands the list of known instances. Importantly, it goes beyond just the better known private stations and identifies where landowners secured their own prerogatives regarding the use of the network in some way. The full list (PDF linked at the end of the article) runs to 114 examples; 72 in England, 33 in Scotland, 4 in Wales, and 5 in Ireland, across 57 different railway lines.

Definitions and caveats

One of the challenges of cataloguing is ensuring that there is consistency and clarity, so below are the definitions I have used:

- Private station: a place on a railway line with one or more buildings, restricted to a specific group of people, to enable them to get on or off a train

- Private halt or platform: an unstaffed location on a railway line with either no buildings or only temporary structures but with a platform, restricted to a specific group of people, to enable them to get on or off a train

- Private waiting room: a purpose-built waiting facility, restricted to a specific group of people, within a station which otherwise remains open to use by the general public

- Station of convenience: an otherwise publicly accessible facility on the network but where the location is known, or there is convincing circumstantial evidence, to have been determined by a local landowner

Based on these definitions, my research shows where there is evidence that the siting, service, or facilities of the stations were influenced by the proximity or power of the local landowner.

This research was just for my own interest so there are methodological challenges. I have not checked every station, though I did review all 16,000+ entries in Butt’s ‘The Directory of Railway Stations’ (1995) for references to the names of country houses or locations where I know one exists (or did exist) and other related books. I have also spend hours traversing the railway lines on the Ordnance Survey 1888-1913 maps via the brilliant National Library of Scotland website. My knowledge of Welsh and Irish geography and houses is not as extensive as for England and Scotland so other examples have almost certainly been overlooked. I am also definitely not a railway historian but I do love railways.

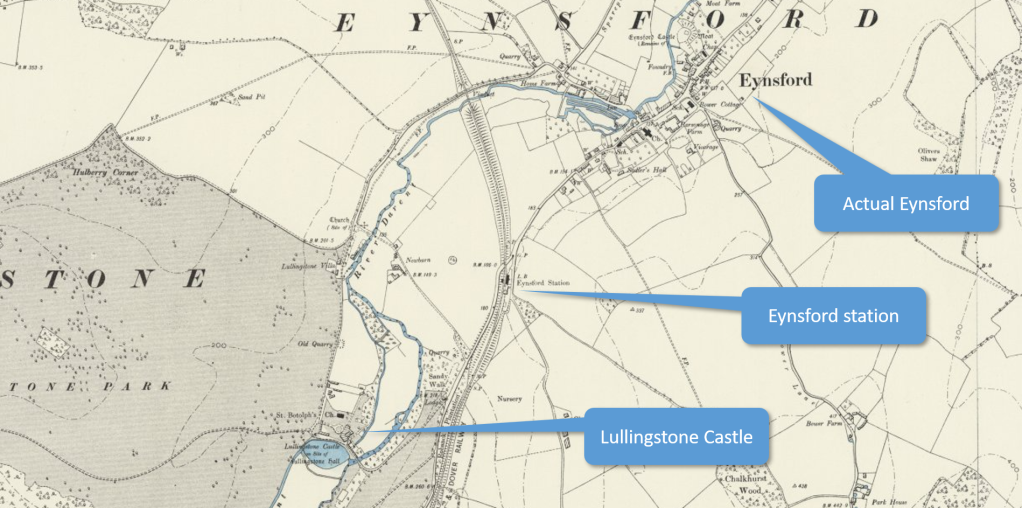

Also, there are the ‘possibles’. This is where although there’s no evidence of privilege, a station just appears to be closer to an estate than its urban namesake. For example, Eynsford station which is noticeably south of the village it’s named after but close to the lodge entrance for the Lullingstone estate. There is almost a gravitational distortion where the power of a local estate has pulled the station towards (or pushed it away from) it by varying degrees. These types have been added to a separate list as too circumstantial (but if someone has the GIS skills, they may be able to identify other anomalies). Also, I have not examined primary documents such as railway company or landowner correspondence.

For the landscape historian, it would also be interesting to compare maps of the estate drives before and after the arrival of the railways to determine if an owner took advantage of the new connections to change the introduction to the estate and house, and the subsequent impact on the development of the parkland and the impact on landscape design (approaches from stations, hiding lines or making a feature of them). An examination of appropriate sales particulars may also indicate the relative importance given to these facilities, especially compared to other attributes.

If someone has a list of railway company directors, cross-referencing their country houses may highlight others as it seems to have been a relatively common perk. Also, it’s hard to show where there was a negative influence; the landowner who did not want the railway near them and so forced the line away from what perhaps might have been the optimum route. Anyway, if someone did want to take it further, these are all good branch lines to explore.

Making tracks

The earliest history of railways can be traced to landowners, though not for the carriage of themselves. The first wagonways were created to assist with the extraction of mineral resources from their estates and transportation to shipping hubs. There is some dispute as to the earliest but one of the best developed was the Wollaton Wagonway. Constructed in 1603-04 by Huntington Beaumont, in partnership with Sir Percival Willoughby, it hauled coal from the Strelley mines on the latter’s Wollaton Hall estate.

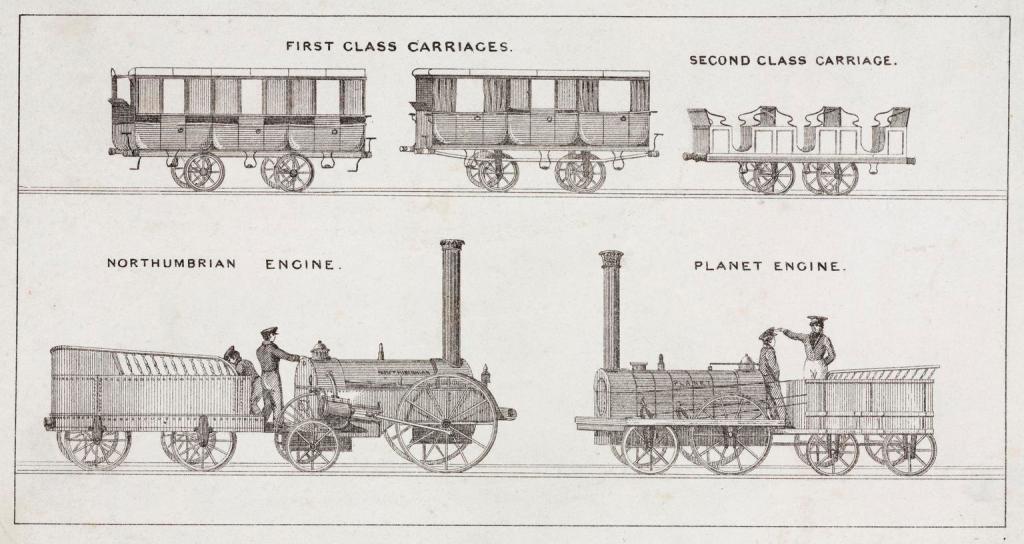

The very first fare-paying passenger service in the UK – though using horses, rather than steam power – was the Oystermouth Railway at Mumbles, south Wales in 1807. The first railways in the modern incarnation to carry passengers and freight were the Stockton & Darlington, which opened in 1825, and the Liverpool & Manchester, which opened in 1830.

The Stockton & Darlington was proposed as a challenge to the Earl of Strathmore’s proposal in 1818 for a canal from his Evenwood colliery to the river near Stockton, using the statutory powers of compulsory purchase to acquire the necessary land. Commercial interests in the places bypassed by the Earl’s canal considered building their own canal but were persuaded to consider the then revolutionary idea of a public tramway or railway (they hadn’t decided which, even when the Stockton & Darlington Railway Bill was put before Parliament in early 1819). In an early sign of the influence of landowners, Lord Eldon opposed the bill due to the loss of substantial ‘wayleaves’ income paid by canals to cross his land, until they agreed substantial compensation. The Earl of Darlington opposed the idea due to the potential negative impact on his foxhunting and so the route was duly altered to avoid his favoured coverts.

The bill finally received Royal Assent on 19 April 1821, duly authorising a line with a total distance of 36.75 miles, which included a main line of 26.75 miles from the Witton Park colliery to Stockton-on-Tees. From this foundation, what’s particularly remarkable about the development of the railway is the scale and pace. By 1852, there were over 7,000 miles of rail track in England and Scotland, and by 1875, over 70 percent of the ultimate total route mileage had been laid. To emphasise the value of the rail industry, the gross revenue in the period 1870-75 was £254.1m, just slightly ahead of the equivalent revenue for the coal industry at £248.7m.

From the start of the idea of transportation using fixed routes – whether roads, canal, or rail – the power of the owner or occupier of the land has been paramount. This has had a profound impact on the pattern of land use across the country, initiating or accelerating urban growth, or stifling it. The routes ultimately took the path of least resistance; be it geographic, political, legal, or financial. It’s hard to underestimate the profound effects that these decisions have had in the shaping of the country as it is today – the towns which became cities, those which missed out, and the patterns of land usage which affects every aspect of our lives.

Railways: friend or foe?

With any revolution, the outcome is often simultaneously reviled and glorified. The sinuous spread of the railways across Britain and Ireland from the 1820s was both of these and more. At first, it was a dirty, noisy, dangerous contraption. Loathed by the poet William Wordsworth, he lamented in an 1845 sonnet its ‘rash assault‘ on ‘thou beautiful romance Of nature‘. Three decades later, John Ruskin’s contemptuous descriptions of his fellow travellers in Letter 69 of ‘Fors Clavigera‘ did little to add any glamour, describing how ‘The rest of the crowd was a mere dismal fermentation of the Ignominious.‘. By contrast, no lesser figure than the artist J.M.W. Turner looked at these same engines and painted a projection of power and grace.

As the prestige of the railway grew anyway, not least through the patronage of Queen Victoria, so too did the opportunities, especially for well-connected landowners. Certainly, there was the chance for investment and profit. Beyond that, perhaps one of the most attractive was to bring convenience and pre-eminence to those who could bend the tracks to their will. It was the opportunity to appropriate a public good for private benefit through their influence on the infrastructure of the burgeoning rail network.

The manipulation of the power of the network took various forms. From the heights of entirely private stations endowed with powerful legal rights to halt trains, to the creation of exclusive facilities at otherwise public stations, the power also manifested in the overt influence of siting stations to create new approaches to their country estates.

Obstruction and opportunity

In the early days, the main concern for the landowner was how to avoid the dreaded statutory powers of compulsory purchase which had forced the canals through their lands. This meant that the railway surveying parties were often met with outright hostility and occasional violence (see ‘The Battle of Saxby’ aka ‘Lord Harborough’s Curve‘). Where physical methods were unsatisfactory, landowners often deployed their greatest weapons – their wealth and the law.

George Stephenson, and his son Robert, were two of the most successful and prolific railway engineers of the era. They stated that the ideal railway should follow the most level route, which could be constructed the most economically, but which should avoid the park and gardens of country estates. In reality, it was rarely possible to satisfy the first two requirements given the resources employed in the protection of the third.

Each proposed railway required two key components; an Act of Parliament to authorise the development and operation, and substantial capital, of which a portion had to be deposited when the draft Act was laid before Parliament. These Acts were a hostage to the demands of the often hostile landowners who sought to either include their every demand or very generous financial terms, which, if the bill passed, would satisfy them (win!), or increase the build costs for the railway to point where it became uneconomic to continue (win!). For example, the Duke of Cleveland opposed the Northern Counties Union Railway but agreed to sell his land for £35,000 above its market value, knowing that it would likely bankrupt them. It did and delayed the railway reaching Barnard Castle for over ten years.

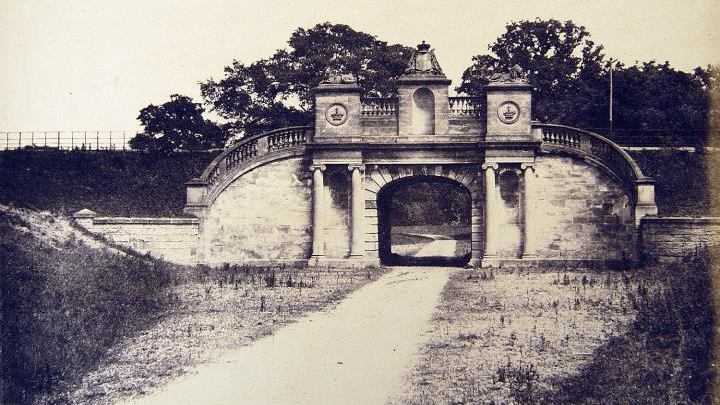

If they objected to the railway for aesthetic reasons, they might demand an expensive features which benefited them such as a tunnel to hide the line (Marley Tunnel on the South Devon Railway for Sir Walter Carew at Marley House, the Haddon Tunnel on the Midland Railway for the Duke of Rutland at Haddon Hall, or the Gisburn Tunnel on the Blackburn-Hellifield line for Lord Ribblesdale at Gisburne Park). Alternatively, an elaborate ornamental bridge such as the two on the Coventry-Leamington line: one for the Gregorys of Styvichall Manor, and the second for Lord Leigh at Stoneleigh Abbey, or the particularly fine example on the Shugborough estate for Lord Lichfield.

However, as the railways became more powerful and wealthy and socially acceptable, smarter landowners saw an opportunity to influence the development of the railway, bolster their local prestige, and also make substantial amounts of money.

Others were more amenable. When George Stephenson proposed a route for the London & Birmingham railway through Uxbridge, Amersham & Aylesbury, every affected landowner rejected it. However, the Countess of Bridgewater at Ashridge Park, summoned Stephenson and suggested that the line followed the Grand Junction Canal through her land at Berkhamsted and Tring. Scottish landowners often supported the railways as a means to more easily transport their coal and provide quicker and easier access to their remote houses. The Duke of Devonshire provided land for free to the Cromford & High Peak Railway, and in actual Devon, Sir Thomas Acland gave his land in the north of the county as it increased the value of what he retained, and Sir John St Aubyn was as generous in the south. In Essex, Lord Taunton actually returned £15,000 of the £35,000 he had received when he realised that the effect of the railway on his estate was less than anticipated.

‘This train will be calling at…your house’

Wealth is power, and power is best demonstrated through its use. Being able to have a train line or station built to serve your country house and securing rights to demand that the public service be altered to your whims is a very piquant demonstration of both.

Private railway lines

Many ducal estates appeared to have been somewhat allergic to the railways, with them neither running through their land or even that close. This can be seen in Nottinghamshire, where the Thoresby, Welbeck, and Clumber estates cover an area of almost almost 100 square miles without a line running through it. The Duke of Atholl objected to almost all railways, and specifically, the Perth & Dunkeld Bill of 1837, primarily to protect his income from the tolls on the Dunkeld bridge. The Duke of Buccleuch’s vast Scottish estates blocked almost every route from Carlisle to Edinburgh and Glasgow. Eventually, a line was created but he forced it to be over 1.5 miles from Drumlanrig Castle and via a (undoubtedly expensive) 0.75 mile tunnel.

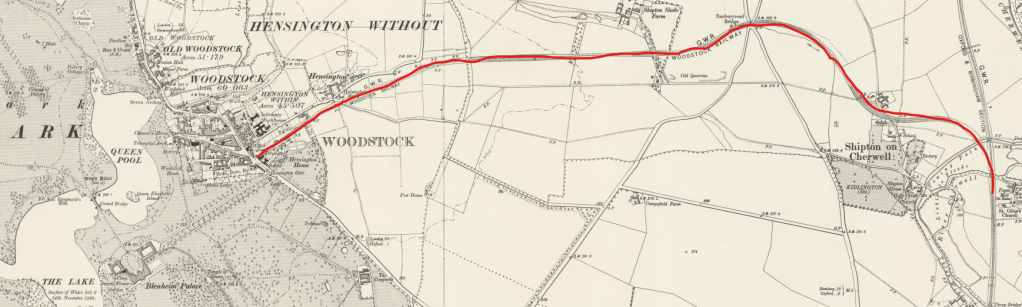

By contrast, the Duke of Marlborough took after the Duke of Sutherland and privately financed his own line; the 4-mile branch line, the Blenheim and Woodstock, which connected his seat at Blenheim Palace to the Great Western Railway at Shipton-on-Cherwell. The Blenheim and Woodstock ran privately from 1890-1897, before being absorbed into the Great Western, though it eventually closed in 1954. The Duke of Sutherland’s Railway was longer, both in distance, at 17 miles, and operating privately, from 1870 until 1884, when it became part of the Highland Railway and which is still part of the Far North line today.

Private stations

Private lines were clearly a very expensive indulgence and the creators seemed happy to eventually pass responsibility for them to existing, larger operators. Although they lost some of the prestige of having their own exclusive line, they also would have no longer been liable for the undoubtedly substantial running costs. After all, a wealthy person doesn’t remain one by spending money. Other, perhaps wiser, landowners took the ‘have your cake and eat it approach’ by requiring stations to be sited for their convenience and their exclusive use. They occasionally also enjoyed legally enforceable powers to stop trains on the lines provided by the public operators who wished to take their routes across their land.

However, the first private station was a mere wooden shed, opened in 1838. It seems that Sir John Tyssen Tyrell was the first to demand such a right when the Eastern Counties Railway (ECR) sought to use part of his estate are Boreham House, Essex, for the route of their new line. He also secured the right that he could stop any train which passed through. This agreement remained in force until his death in 1877 when, in perhaps an expression of frustration at these type of arrangements, the ECR demolished the wooden shed within a day or so of his funeral, thus rather emphatically terminating the arrangement.

These stations are fascinating examples of the power of land ownership. Some ownership was subtle, others more overt, and Seaham Hall station was definitely the latter. The arrival of the railway to Seaham was part of an ambitious plan to transform the seaside village into a major harbour, primarily for the shipping of coal from the Durham coalfields. The coalfields were originally part of the vast inheritance of Lady Frances Anne Vane-Tempest of 65,000 acres which included large tracts of County Durham. After her marriage to Charles William Vane, 3rd Marquess of Londonderry in 1819 (who had to take her surname as part of the deal for her inheritance), they developed the idea of a more efficient and integrated approach to the extraction and transportation of coal.

Seaham Hall was originally the seat of Sir Ralph Noel (who, coincidentally had also taken his wife’s surname to qualify for a substantial inheritance), but was acquired by the Vanes in 1821 for £63,000 (equivalent to £5.7m at 2021 values) at what was intended to be the gateway to their domain. With their extensive control of the land required to develop the railway across the entire county, agreeing to a private railway station was a small indulgence in deference to their influence.

However, the family only used Seaham Hall infrequently as they owned other properties including the palatial Wynyard Hall in the same county but also time at Mount Stuart in Northern Ireland. The station opened in 1875 as part of the Londonderry, Seaham, and Sutherland Railway, with the Marquess enjoying the right to ‘to stop other than express trains within reasonable limits‘. This right was retained until 1923 (though only exercised four times between 1900-23) when the line came under the control of the London & North Eastern Railway who requested this privilege be extinguished. Once this was agreed, the station was closed.

For those who were directors of railway companies, a private station was a considerable perk of the job. George Hudson (b.1800 – d.1871) was famed as ‘The Railway King’ due to his extensive influence over the Midlands rail network. Initially, he was lauded for financing and pushing the creation and ambitions of the York and North Midland Railway (YNMR). Ultimately, both his finances and reputation were ruined through his dubious practices. His achievements included facilitating the railway connecting London and Edinburgh, making York an important railway junction, and merging smaller railway companies to create the Midland Railway.

Hudson was a strategic thinker who saw possibilities, which included how to stymie his rivals. One example was leasing a competing line, the Leeds and Selby Railway, for £17,000 per year and promptly shutting it to ensure trains had to use his route via Castleford. Another example was his purchase of the Londesborough Hall estate, just north of the town of Market Weighton, Yorkshire, which despite its small size, was the junction for no less than four branches of the North Eastern Railway.

The estate was purchased in September 1845 for the substantial sum of £500,000 (c.£52m – 2021 value) partly to frustrate the plans of a rival, George Leeman, to build a line from York to Market Weighton, and partly as an investment for his sons. With the new line running from Market Weighton to York, completed in 1847, Hudson wanted to add his own private station and so had one built at the end of a grand avenue of trees to the west of the house on that line. As Hudson’s dubious empire collapsed around him in the late 1840s, one of the accusations was of inappropriately having used NER’s own money to build the station without authorisation and formed part of their claim against him which totalled £750,000. Londesborough Park was sold in 1850 to help pay his debts and the private station closed in 1867. The station building was renamed Avenue House and survived as a private home until it was demolished in the 1960s. Remarkably, where there was once four lines, there are now none connecting to Market Weighton.

Relatively few owners really wished for the expense of building and maintaining a full station, so some opted for a cheaper version.

Private halts or platforms

The halt was usually a rather primitive structure, often scarcely more than a small platform and shed to serve as a waiting room – though some were more substantial. However, that didn’t mean they wouldn’t be invested with substantial powers to command that the mighty locomotives stop there as they would the grandest metropolitan station, but with the advantage of substantially lower running costs.

Some of the remotest examples of private railway use were in the Scottish Highlands. With very infrequent usage, there was little need for a substantial building – though those having to wait in the rain may have disagreed. At the most basic level, the station was simply a raised wooden platform, long enough for a carriage or two, with a rough access drive to rejoin the nearest road. Yet, these platforms were vital in securing the agreement of the landowner to allow the railway to cross their land.

For those with a little more investment in their comfort, a small wooden building was often considered sufficient to meet their needs. For others, they blurred the lines between the halt and a station.

At the latter end of the scale, Avon Lodge Halt, Dorset, is perhaps one of the more infamous over a dispute as to when is a train service not ‘ordinary’. The halt was one of two built to secure the agreement of James Howard Harris, 3rd Earl of Malmesbury, for the Ringwood, Christchurch and Bournemouth Railway, which opened in 1862, to cross his land. As with most of these agreements, it was included in the legislation authorising the construction of the railway, giving it full legal force. Specifically, Section 27 of the Ringwood, Christchurch and Bournemouth Railway Act 1859 states that:

That the company shall erect and for ever maintain a lodge at the point where the railway will cross the occupation road numbered 29 on the plans deposited for the purposes of this Act in the parish of Ringwood, being the northern entrance to Avon Cottage, and the owner or occupier for the time being of Avon Cottage shall at all times have the right of exhibiting at that lodge a road signal, being a red flag by day and a red lamp at night, for the purpose of stopping any “ordinary” train to set down or take up passengers; and whenever such signal shall be visible in reasonable time for the purpose, the company shall cause any such ordinary trains to stop at such point, and shall take up and set down passengers accordingly.

However, just a year after it had opened, in June 1863, Avon Castle and the halt were for sale. No copy of the sales particulars seems to be available but one can imagine they extol the virtues of the halt and the associated legal powers. The house and halt sold that year to John Edmund Unett Philipson Turner-Turner for £14,300 and it would be fascinating to know how much of the value was attributed to the halt and the associated privileges.

The arrangements continued until March 1873 when a dispute arose as to the meaning of the word ‘ordinary’. In that year, the London and South Western Railway had started an express Bournemouth-London service. Having to stop at Avon Lodge would delay it to such an extent, and inconvenience the other passengers, as to make it commercially unviable. As stated in the legislation, the owner of Avon Castle had the rights enabling the ‘stopping any “ordinary” train‘ and Turner went to court to force the railway to give him the power over the express. However, in January 1874, the judge disagreed that ‘ordinary’ applied to the express service so the Turners had to to satisfy themselves with local trains.

Despite this setback, Turner continued to push the boundaries of his powers under the legislation. The original privilege was clearly intended to apply to the owner and their family. However, during the early 1890s the house became a hotel (as shown on the Ordnance Survey map). To what was probably the considerable irritation of the train company, the hotel made it a feature that trains would be stopped at their private station – an odd democratisation of the original aristocratic privilege. The Turner family sold up in 1901, and due to dwindling passenger numbers, the station was closed in 1935.

Private waiting rooms

For those who wished to avoid the expenditure of ownership but still have some physical manifestation of their power, a private waiting room was an expedient solution. It carved out something private from the public space, creating a sense of ownership through often luxurious fittings and exclusive access.

Private waiting rooms could be combined with the latent power of having influenced the siting of the station. One imagines that those locally would have been acutely aware of the abstract power which had created the physical presence of the station so the idea of a permanent reminder of that power within the station buildings wouldn’t have seemed so surprising.

When Clifton & Lowther station, Cumberland, opened in 1846 on the Lancaster & Carlisle Railway (part of the London & North West Railway), it was the nearest for the Earl of Lonsdale at Lowther Castle. The line displays all the characteristics of landowner influence; a line which curves eastwards around the entire parkland with most of it hidden in a series of cuttings with the station carefully sited away from the main north/south axial views from the castle. The price the Earl extracted for the station was the right to stop any train which was due to pass through, even if it wasn’t scheduled to stop there. In 1862, the Eden Valley line opened, providing a better alternative for cross-Pennine passengers. This led to a reduction the number of trains using Clifton & Lowther, though it didn’t close to passengers until 1938. However, a new station, Clifton Moor, was opened on the new line in 1862, it featured a dedicated private waiting room for the Earl and his guests. It’s not known how often the station or the right to stop trains was used but the station closed to passengers in 1962 with the Earl’s waiting room converted into a private house.

The private waiting room enabled a degree of subtle, yet paradoxically overt, ownership by the landowner over an station, acting as yet another reminder of their local influence.

Station of convenience

Perhaps the wisest owners were those who were happy to share the facilities but by the mere fact of choosing the location of the station, secured the greatest personal convenience for themselves.

A majority of these stations were the product of the nineteenth-century, but a handful were created at the turn of the twentieth-century, demonstrating the continuing power of the landowners. One of the most notable was the station at Acton Turville, Gloucestershire, in 1903. The actual name of the station was Badminton after the nearby stately home of the Duke of Beaufort. Given the heavy financial demands of many landowners, the Great Western Railway must have been delighted when His Grace agreed to provide the land required for the railway for free. The only requirement was for a station at Badminton to provide access for the Duke, family and guests and that express trains were required to stop should any of this exclusive group wish to alight. The station was a late arrival, opening in 1903, but featured a suitably plush, red-carpeted waiting room with ducal crest. However, the GWR’s delight had turned to frustration by 1963, as due to the immense inconvenience of having to stop express trains and also otherwise low passenger numbers along the line, British Railways asked Parliament to set aside the agreement. However, Parliament upheld it and so despite closing all the other stations on the line, Badminton retained its passenger service until 1968, when the Duke finally agreed to cede his rights, making it one of the last to enjoy such privileges.

For the landowner who prioritised convenience over exclusivity, simply enjoying the privilege of placing a station at the most convenient position was sufficient. Though they had to share the facilities with the public, the absence of financial responsibility and the overt class divisions meant that these stations were perhaps the most egalitarian of these arrangements.

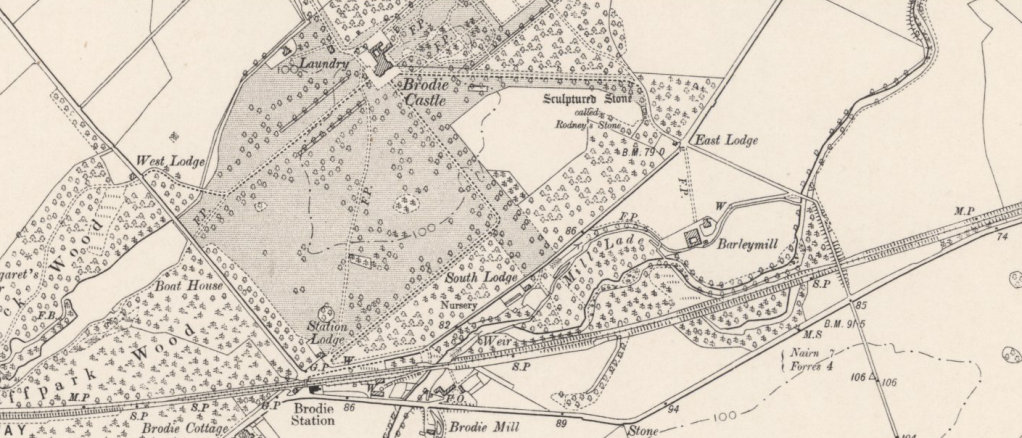

For some landowners, this was a chance to rethink the landscape of their estates. Owners traditionally considered the approach via the roads and estate drive, owners may now have to consider how to hide the train itself whilst creating access and a suitable sense of arrival for their guests. For some, this was as simple as extending or creating a road and adding a new gate such as Station Lodge leading from Brodie Castle, which faced Brodie station when it opened in 1857 on the Inverness and Aberdeen Junction Railway.

Similarly at Newstead Abbey, a grand avenue of trees emphasised that the approach from the station was an important element of the grandeur of the estate.

Another example shows the lengths to which a landowner would go to when creating a sense of arrival. At the now demolished Blankney Hall, Lincolnshire, the owner, Henry Chaplin, had the option of simply taking his guests along the public roads, from Blankney & Metheringham Station, which opened in 1882 on the Great Northern and Great Eastern Joint Railway. Instead, he created a parallel access road which ran for almost a mile on his land, grandly demonstrating his estate and also providing a higher degree of privacy.

Influencing the siting of stations to the landowner’s convenience seems to have been the most common approach; a powerful but quiet means of both exerting and exhibiting power.

Ireland

Prior to the Irish War of Independence, which ended in the creation of the Irish Free State in December 1922, the railways on the island of Ireland were managed and integrated with the rest of Great Britain. The history of the railway in Ireland ran broadly in parallel with that of the mainland. The Dublin and Kingstown Railway (D&KR) was built in 1834 with dozens of other companies being formed in the following decades. At its peak, by 1920, the rail network extended to 3,500 route miles. The process for the authorisation for the development through the use of Parliamentary legislation and so too came the demands for landowner privileges, though much fewer than elsewhere with only five identified so far.

How to catch a train (station)

The exact discussions by which these concessions were raised, negotiated, and agreed are not obviously unavailable, though there are probably meeting notes in a rail company or landowner’s archive somewhere. The negotiations would have been probably conducted by the land agent for the estate and the family lawyers, under the direction of the landowner.

The era was heavily influenced by those with wealth, those who controlled access to land, and those who had parliamentary influence. For a majority of these private stations and concessions, conveniently those who secured such privileges often had at least one of these three – and sometimes all of them.

Although the 1832 Reform Act had abolished the ‘rotten boroughs’, for many landowners, their control of large areas of a particular location often enabled them to secure their local parliamentary seat, to neatly complement their country seat. These concessions – particularly a private line or station, with stopping rights – required legislation, and landowners who were also MPs were in a prime position to ensure that such amendments were drafted favourably, included in the draft bills, and supported by fellow MPs.

Another important factor was that the financing of the development of the railway was provided entirely by private capital. For those able to commit substantial amounts, their status as an investor could be enhanced with a directorship of the railway company.

So, the wealth which enabled someone to become a landowner (and therefore provide the vital permission for the line to cross their land), also enabled them to be able to invest enough to become a director, whilst sometimes also being an MP. These overlapping spheres of influence can be seen in the total number of MPs who were also directors of a railway company:

| Parliamentary period | Directors as MPs | As a percentage of total MPs |

| 1865 | 157 | 22% (of 713) |

| 1868-84 | 124 | 16% (of 783) |

| 1885-91 | 83 | 12.5% (of 663) |

| 1892-1905 | 73 | 10% (of 740) |

| 1906-14 | 42 | 5.7% (of 739) |

From the number and widespread distribution of these privileges, it seems that they were quite a common and accepted perk of their support – or at least acquiescence – where the route crossed their land.

The last train will be departing…

Given the significant inconvenience and obvious inequality and inconveniences that these privileges created, their long-term survival was always unlikely. A combination of the amalgamation of the train operating companies, the professionalisation of the service, and the introduction of external capital, all diluted the leverage that created and sustained these special arrangements.

The contractual rights were well known and easily referenced in the debates in the Houses of Parliament on the British Railways Bill. Clause 34 was specifically included to target those covenants ‘requiring that company to provide and to maintain a station for the use of the vendor of the land’, of which the Minister, John Hay, claimed that the Railways Board had said there were over 100 in the Western Region alone. The rights of the landowners were in some ways considered more with frustration and amusement than any great outrage. John Dugdale (Labour MP for West Bromwich, 1941-1963) rather wryly dismissed the situation saying:

“I am not entering into the question of the Duke of Beaufort’s agreement. I am sure we are all sorry for him. Apparently he is a very distressed man. It is a sad thing; here is this great gentleman who unfortunately finds that there is no railway station between Swindon and South Wales at which a train will stop and he has to go in his motor car to Swindon. It is a great hardship for him, and we are distressed that it could happen to him…”

(Debate 26 February 1963, column 1165)

Though the Duke of Beaufort managed to protect his rights until 1968, the British Railways Act of 1963 finally ended almost all such indulgences. At a stroke, it removed an extensive, complex, and eccentric pattern of privilege, created by the unique circumstances of the birth and growth of the railways.

The list

>> List of private or privileged train lines, stations, and facilities [PDF, 702KB]

Are there others?

Almost certainly. For the reasons outlined in the methodology, there will be others which relate to country houses which I’ve missed. So if you are aware of them (or any mistakes), please do feel free to share your knowledge in the comments and I’ll update the list below accordingly.

Selected bibliography | Credits

- Paterson, Anne-Mary, Lairds in Waiting (Dorchester: The Highland Railway Society, 2021)

- Vaughan, Adrian, Railwaymen, Politics & Money (London: John Murray, 1997)

- Wade, George A., ‘Private Railway Stations’, The Railway Magazine, XIII.July to December, (1903), 398-403.

- Biddle, Gordon, ‘The Railway Surveyors‘, (Shepperton: Ian Allan Ltd, 1990)

- Butt, R.V.J., The Directory of Railway Stations (Sparkford: Patrick Stephens Limited, 1995)

- Croughton, Kidner, Young, Private and Untimetabled Railway Stations (The Oakwood Press, 1982)

- Ruskin, John, ‘Letter 69 – The Message of Jael-Atropos‘, Fors Clavigera: Vol. VI (London: George Allen, 1907) 687-695, paras 5-10.

- British Railways Bill debate – 26 February 1963 (Hansard)

Also, credit to all the enthusiasts and experts who have contributed to Wikipedia, Railscot, and numerous individual websites, whose help has been invaluable.

![An Historical Account of Corsham House in Wiltshire, the seat of Paul Cobb Methuen [1806]](https://countryhouses.files.wordpress.com/2017/03/historical-account-of-corsham-house.jpg)

![Opening Times in 'An Historical Account of Corsham House in Wiltshire, the seat of Paul Cobb Methuen' by John Brittan [1806]](https://countryhouses.files.wordpress.com/2017/03/historical-account-of-corsham-house-opening-times.jpg)

!['Plan of the Library Story' from 'The Peak Guide; containing the topographical, statistical, and general history of Buxton, Chatsworth, Edensor, Castlteon [sic], Bakewell, Haddon, Matlock, and Cromford' by Stephen Glover of Derby [1830]](https://countryhouses.files.wordpress.com/2017/03/chatsworth-floor-plan.jpg)