Following the account of the Birmingham riots in 1791, and those accompanied the Second Reform Bill in 1831, which destroyed a number a country houses, this final part of the series looks at the violent destruction in the 20th-century.

Suffragettes

With the slogan ‘Deeds not Words’, the call to action in the campaign for the right of women to vote was as clear as the potential for escalation.

Although the Suffrage movement included a number of organisations, some favouring constitutional reform, others a more militant approach. The most prominent of the latter was the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), which had started as a small Manchester-based organisation in 1905-06. Just a few years later, as its profile rapidly grew, it had become a well-organised, London-based group.

The WSPU’s early strategy focused on embarrassing the Liberal government by mass heckling any appearance by a minister. These tactics were effective; they either shut down the meeting, or the protesters were forcefully ejected – both results making their cause more prominent. However, as the meetings became increasingly all-ticketed and well-policed, how could they ensure that their voices were still heard?

Violence begets violence. The force with which the women protesters were met – including beatings, sexual assault, imprisonment, and force-feeding – created an atmosphere of retaliation. As they became increasingly disillusioned by the lack of progress using Parliamentary reform, by 1909, the situation had escalated, with over thirty incidents of the suffragettes attacking meetings, including stone-throwing. This sporadic use of violence continued until 1911, mainly aimed at those representing the government, either as ministers or civil servants.

After 1911, the range of acceptable targets expanded to include commercial interests and the property of those in government. Annie Kenney, who worked closely with the Pankhursts, stated that ‘that: ‘It was at this time [1912-13] that the burning of houses was resorted to. Both Christabel and her mother were against taking of human life, but Christabel felt the times demanded measures, and burning she knew would frighten both the public and Parliament.’ (Annie Kenney, Memoirs of a Militant (London, 1924), 187). Christabel Pankhurst wrote in 1913; ‘If men use explosives and bombs for their own purpose they call it war, and the throwing of a bomb that destroys other people is then described as a glorious and heroic deed. Why should a woman not make use of the same weapons as men. It is not only war we have declared. We are fighting for a revolution!’

The WSPU’s strategy rested on the belief that ‘There is something that governments care far more for than human life, and this is the security of property, and so it is through property that we shall strike the enemy.’. In a speech in Cardiff in March 1913, Emmeline Pankhurst vowed to strike at what she thought was most valued by society: ‘money, property and pleasure’. However, she was very clear that their target was property, and not people:

‘The Suffragettes have not done that, and they never will. In fact the moving spirit of militancy is deep and abiding reverence for human life.’.

And so the destruction of property became a proxy. The pillar boxes represented the state, the shops those commercial interests which supported the government, the homes of ministers and art works in public collections we all assaults which deliberately avoided targeting people.

With the righteous belief that ‘if it was necessary to win the vote they were going to do as much damage to property as they could’, the Suffragettes set about doing so, with country houses an especially tempting target, both for their impact and what they represented.

Whilst Emmeline Pankhurst was held in Holloway prison in April 1913, she recalls that ‘…my imprisonment [in 1912] was followed by the greatest revolutionary outbreak that had been witnessed in England since 1832’ and that ‘Many country houses—all unoccupied—were fired.’. This is repeated by Sylvia Pankhurst in her own account where she states that ‘Many large empty houses in all parts of the country were set on fire, including Redlynch House, Somerset, where damage was estimated at £40,000.’.

On 13 July 1912, two Suffragettes made the first attempt to burn down a country house.

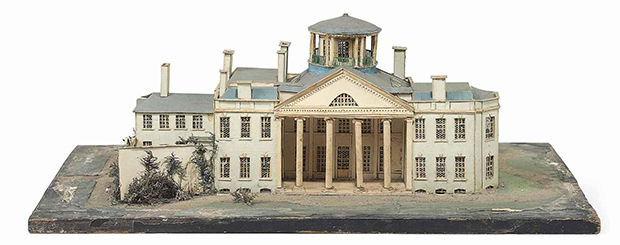

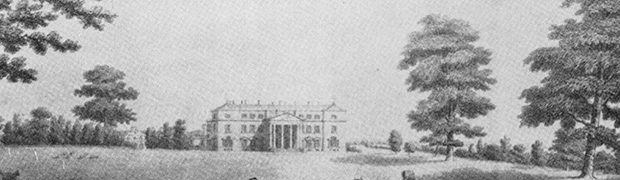

Helen Craggs was arrested at 1am in the garden of Nuneham Courtenay, Oxfordshire – though it’s unclear whether the target was the main house or possibly just the uninhabited east wing, as her co-conspirator Norah Smyth later suggested. The house had been home to the Harcourt family since it had been bought in 1712 by Sir Simon (later Viscount) Harcourt, the successful Solicitor General and Lord Chancellor under Queen Anne, for £17,000. The then owner, Lewis Harcourt, was a member of Prime Minister Herbert Asquith’s Liberal government, which had so strenuously resisted the demands for votes for women.

Nuneham Courtenay had also been an early target as Harcourt had discovered a bomb hidden in a tree in February 1907. He regarded this as ‘a delicate attention to me from the Female Suffragists‘, but it is a uncharacteristically early escalation, in a period when the campaign was still focused on parliamentary reform.

Five years later, Craggs’ bag was found to be carrying bottles of flammable oil, four tapers, two boxes of matches, twelve fire-lighters, picklocks, an electric torch, a glass-cutter – and a note. The note – which rather politely started, ‘Sir’ – went on to state that as she had tried every method of peaceful protest and propaganda, ‘…that it has all been of no avail, so now I have accepted the challenge…and I have done something drastic.’. Although Craggs was a member of the WSPU, and the proposed arson was to have been in their name, neither Emmeline or Christabel Pankhurst were apparently aware of the ultimately unsuccessful plan.

The key question of just how many houses were actually damaged or destroyed by the Suffragettes, seems to be unresolved.

In the late C.J. Bearman’s assessment of Suffragette militancy (An Examination of Suffragette Violence, (The English Historical Review , Apr., 2005, Vol. 120, No. 486 (Apr., 2005), pp.365-397)), he identified a total of 337 incidents which were claimed via the weekly reports in The Suffragette newspaper. Frustratingly, his article doesn’t include the list and his papers are currently inaccessibly (for me) in Hull University library.

However, another significant source is A.E. Metcalfe’s almost contemporary ‘Women’s Effort: A Chronicle of British Women’s Fifty Years’ Struggle for Citizenship 1865-1914‘, published in 1917. Her book includes tables of claimed attacks, with dates, estimated valuations of the amount of damage caused, and where they were reported – but only for January-July 1914. However, other sources give further incidents during this period, so below is an attempt at collating them into a single list of targeted country houses (‘AEM’ indicates Metcalfe’s records are the source).

1913

| Date or Month | Property | Damage assessment | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 19 March | Trevethan, Englefield Green, Surrey | Destroyed | Owned by Lord and Lady White |

| 15 April | Levetleigh House, St Leonards, Sussex | Destroyed | Owned by Mr Arthur du Cros |

| April | Roughwood, Chorleywood, Hertfordshire | Destroyed | |

| 9 May | Farington Hall, Dundee | Destroyed | |

| June | Ballikinrain Castle, Stirlingshire | Severely damaged | Later restored |

| June | Granby House, Wiltshire | Destroyed | |

| 6 July | Royton Cottage, Cheshire | Destroyed | Owned by Lord Leverhulme |

| 13 July | Nuneham Courtenay, Oxfordshire | Undamaged | |

| 13 November | Begbrook House, Gloucestershire | Destroyed | Owned by Hugh Thomas Coles |

| 20 December | Westwood, Bath, Somerset | Destroyed | |

| 21 December | Alstone Lawn Manor, Gloucestershire | Severely damaged |

1914

| Date or Month | Property | Damage assessment | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 January | ‘Stratford Mansion’ | ‘Gutted’ | AEM – unclear exactly which house this is in the entry in Metcalfe’s table |

| 3 February | House of Ross, Perthshire | Destroyed | AEM |

| 3 February | St. Fillans Castle, Perthshire | Destroyed | AEM |

| 3 February | Aberuchill Castle, Perthshire | Partially destroyed | AEM |

| 18 February | Walton Heath, Surrey | Severely damaged | Two bombs planted, one detonated. House being built for Lloyd George |

| 24 February | Redlynch House, Somerset | Destroyed | AEM |

| 10 March | ‘Mansion’, Bruton, Somerset | AEM | |

| 12 March | Robertsland House, Ayrshire | Destroyed | AEM |

| 27 March | Abbeylands House, Belfast | Destroyed | AEM |

| 9 April | Seaview House, Belfast | Damaged | AEM |

| 10 April | Orlands House, Belfast | Destroyed | AEM |

| 22 April | Annadale House, Belfast | Destroyed | AEM |

| 23 May | Stoughton Grange, Leicestershire | Slightly damaged | |

| 1 June | The Willows, Berkshire | Slightly damaged | AEM |

| 1 June | Nevill Holt House, Leicestershire | Slightly damaged | AEM |

| 6 June | ‘Mansion’, High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire | Destroyed | AEM |

| 12 June | ‘Mansion’, Nottingham | Slightly damaged | AEM |

| 29 June | Papplewick Hall, Nottingham | Slightly damaged | AEM |

| 3 July | Ballymenoch House, Ulster | Destroyed | AEM |

| 14 July | Cocken Hall, County Durham | Slightly damaged | AEM |

As quickly as the campaign had started, so it stopped; the WSPU suspended their militant campaign with outbreak of World War One in July 1914. The incredible efforts of women during the war – at home, in service, in factories and hospitals – brought many to their side and support for suffrage grew. On 6 February 1918, the Representation of the People Act of 1918 enfranchised over eight million women and in November of that year, the Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act 1918 was passed, allowing women to be elected as MPs. It would, however, take until 1928 before women finally were able to vote on the same terms as men.

The list above totals 31 attacks on country houses over the two-year period – less than 10% of the total number of significant actions Bearman identified. There are certainly others which I haven’t found yet (and if you know of other possible attacks on country houses, please add a comment below).

Although impressive as a list of targets, particularly given the lack of co-ordination and the inexperience of the protagonists, it demonstrates that country houses were certainly symbolic but were never the main focus for the campaign of destruction. One other aspect worth noting is the number of Suffragettes who were either Irish or active in Ireland – did their campaign inspire the later tactics of the independence movement which were to be so devastating to the country houses of Ireland?

Last flickers of protest

Since the Suffragettes campaign, the country house has largely remained immune from similar targeting though there seems to have been only two similar attacks since, both attached to the long tail of the Irish independence campaign.

On 21 January 1981 at 9:45pm, an explosion blew the front doors open at Tynan Abbey, County Armagh. Armed members of the IRA rushed in and gunned down both 86-year old Sir Norman Stronge and his son, Sir James, who were sitting in the library. They then detonated incendiaries which destroyed much of the house and its valuable contents. The ruins remained until 1998 when they were cleared.

The most recent attack appears to have been the attempted bombing of the late Sir Alistair McAlpine (b.1942 – d.2014) at West Green House, Hampshire in 1990. McAlpine, scion of the famous family of building contractors and Conservative Party treasurer, was actually a tenant of the National Trust, the house having been bought by Sir Victor Sassoon and donated to them in 1957 (though they were not able to take possession until the end of a life tenancy in 1971).

Having found out that his name was on a list of IRA targets, McAlpine and his family left West Green House and moved to Italy. The IRA hadn’t received the change of address notice and on 13 June 1990 detonated a substantial device in the forecourt of the house, creating such extensive damage that the National Trust apparently considered demolition. Thankfully, they instead completed the structural repairs and then leased it to Marylyn Abbot to complete the internal works. It has remained her private home but with the gardens open between May-December and, since 2000, has hosted a yearly opera season.

So, this concludes the three-part series on the violent targeting of country houses in the UK – for religious, democratic, and political reasons.

Despite all that the country house symbolically represents and the myriad connections across society that they possess, the country house in the UK has, thankfully, largely escaped the broad and calculated devastation which has been visited on similar properties elsewhere. This is possibly due to the lack of a similar cause, or better security, or that destruction no longer has the same value, they do remain potent symbols, but ones that hopefully inspire, rather than enrage.

If you’d like to read the rest of the series:

- Part 1: ‘Priestley Riots 1791‘

- Part 2: ‘Reform Act Riots 1831‘

![An Historical Account of Corsham House in Wiltshire, the seat of Paul Cobb Methuen [1806]](https://countryhouses.files.wordpress.com/2017/03/historical-account-of-corsham-house.jpg)

![Opening Times in 'An Historical Account of Corsham House in Wiltshire, the seat of Paul Cobb Methuen' by John Brittan [1806]](https://countryhouses.files.wordpress.com/2017/03/historical-account-of-corsham-house-opening-times.jpg)

!['Plan of the Library Story' from 'The Peak Guide; containing the topographical, statistical, and general history of Buxton, Chatsworth, Edensor, Castlteon [sic], Bakewell, Haddon, Matlock, and Cromford' by Stephen Glover of Derby [1830]](https://countryhouses.files.wordpress.com/2017/03/chatsworth-floor-plan.jpg)