On 8 October 1831, the Houses of Lords voted down the Second Reform Bill. As before, this had proposed moderately extending the electoral franchise and reorganised the distribution of constituencies to diminish the power of aristocratic patronage. Months of agitation, protest, and public meetings had been dismissed by the Lords, their trenchant opposition seeming to offer little prospect of success through parliamentary democracy. As the news spread around the country that evening and over the next few days, riots broke in several cities and towns including London, Derby, Birmingham, Nottingham, Yeovil, Sherborne, Exeter and Bristol, but which also targeted a number of country houses.

The 1830s were a challenging period for the average worker, urban and rural alike. Unchanging political structures left them unrepresented, which, combined with increasing mechanisation and a deterioration in the social support structures which helped the destitute, had pushed the workers to desperation.

The decade started as it meant to continue. In 1830, farmers started receiving letters from a fictitious ‘Captain Swing’ demanding better conditions for the workers and the end to the use of new threshing machines, which reduced the need to employ as many labourers. When the farmers refused, the labourers in first Kent, and eventually every English county, rose up in destructive protest. Their targets were property, specifically the threshing machines which threatened their livelihoods, but also barns and hayricks, in what became known as the Swing Riots (after the eponymous correspondent). Yet, despite their anger being directed at the property of the farmers and landowners, the mobs seemingly did not target their country houses.

At the same time, the simmering resentment of the urban workers at their lack of political representation reached boiling point. The farm labourers directed their anger at the machines and agricultural features which they experienced in their working daily lives. For the urban worker, their revenge was as indiscriminate as it was targeted; entire areas of cities looted and burnt, whilst also specifically attacking the property of those in the political classes who sought to frustrate change.

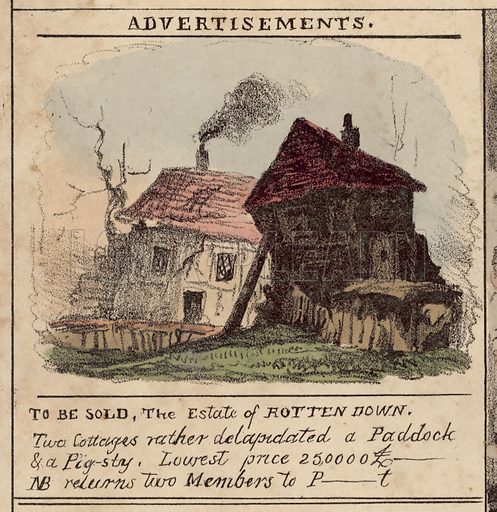

Some in Parliament had recognised the very legitimate concerns about the current political arrangements. Problems included the limited number of voters (just 5% of the population were eligible), the unequal distribution of MPs (did Cornwall in 1821 really require 44 MPs to represent it? It has just six in 2021), and control of the constituencies through patronage. The latter included the infamous ‘rotten boroughs‘, where a handful of electors (or none at all in the case of Old Sarum, Wiltshire) returned one or two MPs; the same numbers as major cities such as Liverpool or Manchester which had populations of over 100,000.

A fear of revolution had always stalked the British ruling class. This was particularly acute in the century which followed the America War of Independence (1775-1783). This marked the beginning of a period which became known as the Age of Revolution (according to the historian Eric Hobsbawn), when the existing social order was overthrown in a number of countries. Although Pitt the Younger had proposed some limited reforms in 1785, the subsequent experience of France, where modest constitutional reforms in 1789 had become a regicidal reign of terror by 1793, largely blunted any attempt at change.

However, by 1830, there was an increasing sense of concern, even in the political classes. The concern was less about the obvious injustices of the current arrangements, but that unless there was change, the anger may result in revolution, as had so recently happened again in France. In January 1830, a new Whig government was formed and introduced modest proposals to reform the parliamentary system. The Tories, with the Duke of Wellington in the vanguard, were staunch in their opposition, defeating the Reform Bill on each of the three occasions it was brought before the House. The views of the Duke were as dark as they were strident; in one letter he thundered:

Matters appear to be going as badly as possible. It may be relied upon that we shall have a revolution. I have never doubted the inclination and disposition of the lower orders of the people. I told you years ago that they are rotten to the core. They are not bloodthirsty, but they are desirous of plunder. They will plunder, annihilate all property in the country. The majority of them will starve; and we shall witness scenes such as have never yet occurred in any part of the world.

Duke of Wellington to Mrs Arbuthnot on 1 May 1830

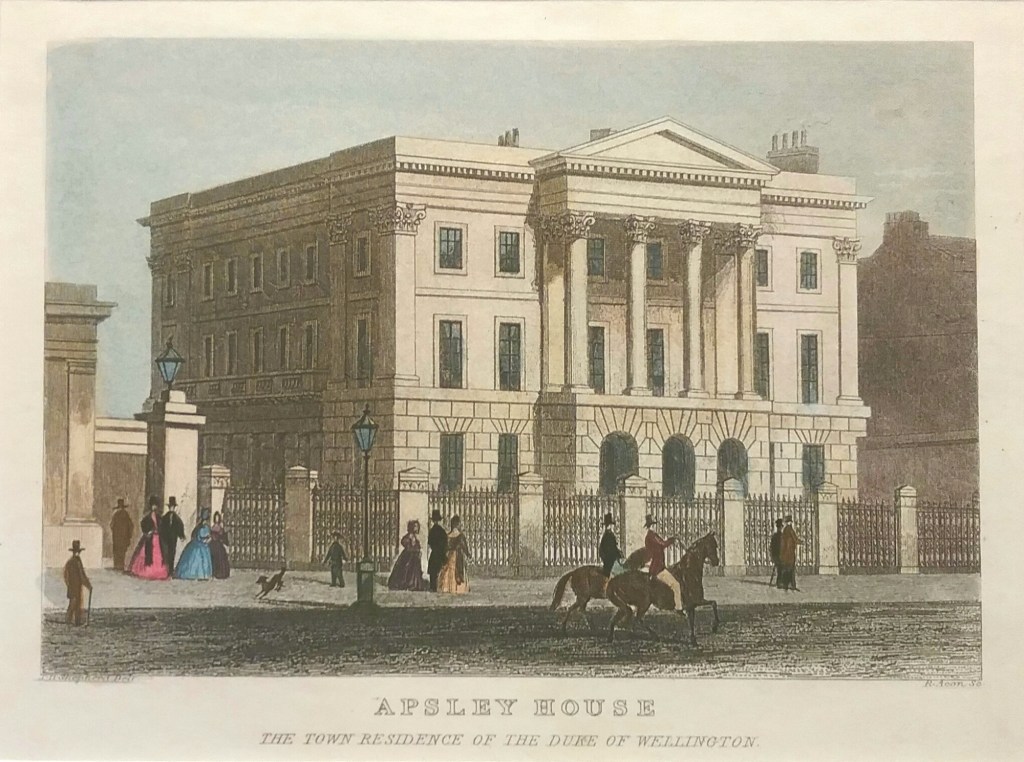

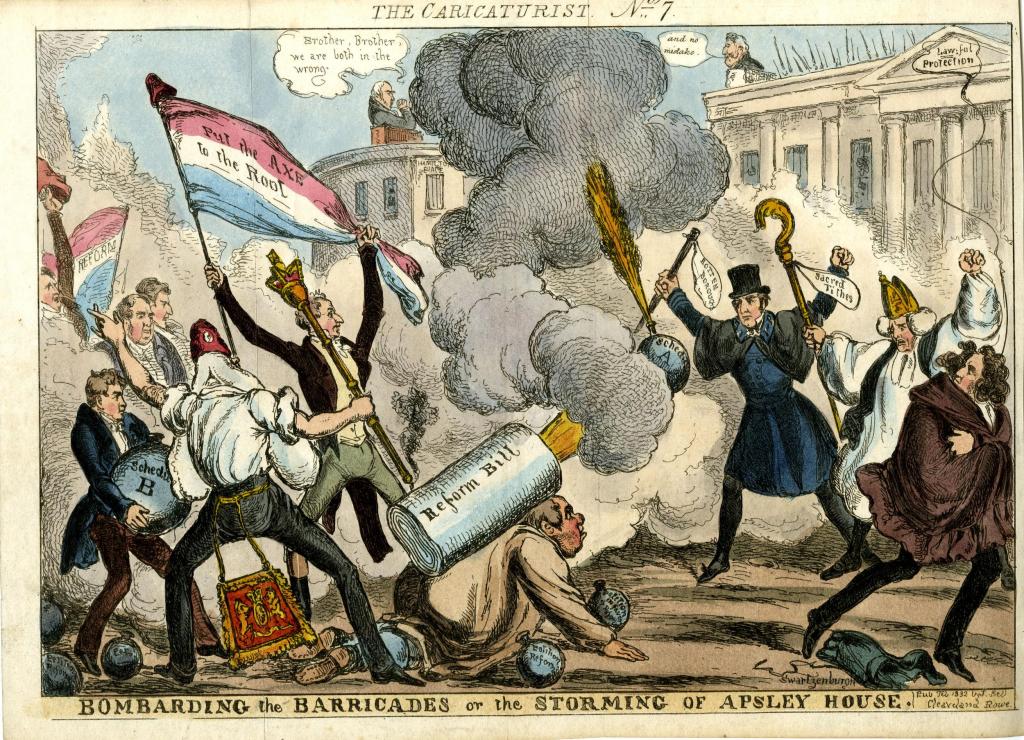

The mob felt equally as enamoured with the Duke. Twice in 1831 they targeted his London home, Apsley House. On 27 April, they smashed thirty windows and threatened to ransack it but were dissuaded by the Duke’s servant, John, who went on the roof and fired blunderbusses in the air to scare the mob off. After this, in June, the Duke had iron shutters fitted to his windows. This earned him his sobriquet of ‘Iron Duke’ – which many today assume was related to his military success, rather than his domestic unpopularity.

In October 1831, this long-running national, class-driven antagonism reached its peak – and country houses stood in the sights of those seeking to make their feelings known to those who were either directly or indirectly frustrating reform and represented the forces of opposition.

Second Reform Bill riots

When the Reform Bill was again voted down by the Lords on 8 October 1831, anger erupted. That night, and over the next few days, messengers, pamphleteers, and newspapers spread the news of the failure to pass the bill. Even though many of those who rioted would still not have met the criteria to get the vote themselves, the bill represented a hope that one day they might – and that hope had been dashed again. As the parliamentary process had failed them, across the country the people turned to a more direct and violent expression of their frustrations and anger.

Derby

As one of the major urban areas, Derby was historically controlled by well-established aristocratic and new plutocratic families – Cavendishes, Cokes, Strutts, and Awkrights, to name a few. However, in the early nineteenth-century it had developed a significant and rapidly increasing urban working class as industrialisation drew many to work in the mills and other industries. Traditionally, Derbyshire farms were much smaller scale and many families enjoyed their putative ‘three acres and a cow‘, providing a degree of self-sufficiency. However, economic hardships had increasingly forced these smallholders to sell up and move to towns and cities; their only remaining option being to enter the precarious labour market. The cause for political reform was therefore met with fertile ground in the county.

In Derby, following 1830 general election, the MPs were both liberal and had supported reform (firmly by Strutt, initially less so by Cavendish, though he later came down more solidly in favour) . When news reached Derby on 8 October that the bill hadn’t passed, the anger of the people was expressed in the violent targeting of the property of those Tories who had been in opposition to it. The rioting continued over the following two days.

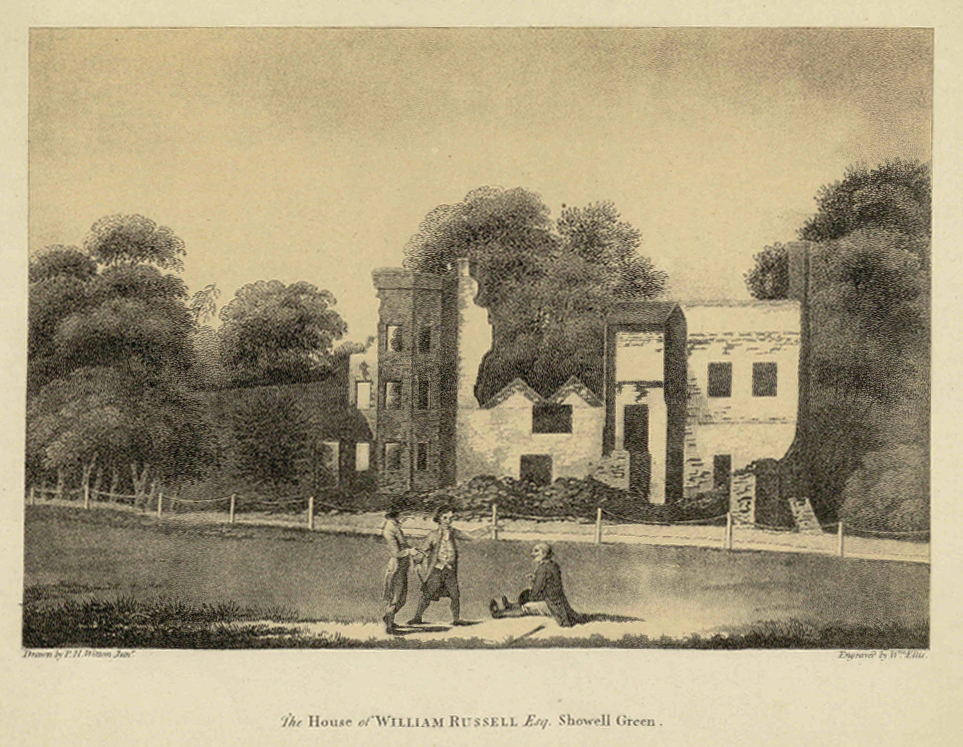

One target was Markeaton Hall, the home of Francis Mundy. The estate was originally held by the Touchets but was sold in 1516 to John Mundy, a former Lord Mayor of London, who claimed to have local ancestry. The original house was replaced in 1750 with a new brick house, designed by an unknown architect who broadly got the proportions right and the details wrong; cramping the façade by placing the windows too close together. A later extension to the north (shown on the right in the photo above) was more successful in spacing them correctly.

These architectural details would have been of little importance to the mob who assembled on 8 October and marched across the 100-acre parkland to express their displeasure. The damage was reported as being extensive (p.g. v, ‘Derby Riots‘ by Thomas Richardson, 1832) but the agitators seem to have stopped short of setting the house alight and destroying it completely, as it was later repaired and appears much as it did in early prints. The house was eventually demolished in 1964 by the ungrateful Corporation of Derby. They had been left the house and 20 acres in 1929 by Rev. Clark-Maxwell, a Mundy descendent, on the condition that the house be maintained and opened for the cultural benefit of the local people. The Corporation, who had previous poor form with other houses they were gifted, let the house decay until they could tear it down.

Also attacked was Chaddesden Hall, Derby, the home of Sir Henry Sacheverell Wilmot, 4th Baronet (b.1801 – d.1872) – who as well as being a prominent local Tory, was also married to the Mundy family. Chaddesden Hall survived and was restored though later urban development led to its sale in 1923 by the Wilmot family in to the Rural District Council. The house only lasted another three years before being demolished and the site and part of the parkland being developed for housing.

Somerset

Despite his estate being in the next county, the opposition to reform focused on Lord Ashley, aka Anthony Ashley-Cooper, the 7th Earl of Shaftesbury, an MP by virtue of a rotten borough (Woodstock, Oxfordshire) and a strong supporter of the Duke of Wellington. His election agents were often the local solicitors and in the Yeovil riots it was they who bore the brunt of the people’s anger when they sought their targets on Friday 21 October. The small town houses of the anti-Reformers in Yeovil were visited in turn. One which suffered the most damage was Hendford Manor, home of solicitor Edwin Newman, which was attacked by the angry crowd, eventually forcing Newman and his family to flee before the house was vandalised, causing £250 damage. Elsewhere in Yeovil, Glenthorne House – also owned by a solicitor – and Old Sarum House and Hendford House, were similarly attacked.

Bristol

The riots in Bristol were some of the most severe and costly in the entire 19th-century. The trigger for the violence was the arrival in the city on 29 October of their senior judge, Sir Charles Wetherall, on his annual visit. Speaking in Parliament in the reform debates, he had lied and said that the people of Bristol didn’t favour reform, despite knowing of a 17,000-name petition demanding just that. To cap it all, Wetherall was a manifestation of the inequitable system as he represented the rotten borough of Boroughbridge in Yorkshire which was controlled by the dogmatically anti-reform Duke of Newcastle. The constituency returned two MPs for an population of 947, of whom the electorate was just 48. Bristol at the same time also had two MPs but for a population of 100,000.

Demonstrators greeted Wetherall with loud protests, which degenerated into riots which lasted three days and resulted in damage totalling over £300,000. Both Bristol MPs, James Evan Baillie and Edward Davis Protheroe, supported parliamentary reform, which seems to have saved them from being targeted. Therefore the mob’s targets were mainly civic buildings including the Mansion House, two prisons, toll houses, the Custom House, Excise Office though around 40 private houses in Queen’s Square and Princes Street were looted and burnt down. The violence remained focused in the city and the only house of note to be destroyed was the Bishop’s Palace, targeted as the Bishop of Bristol had been strongly opposed to reform.

Dorset

Even in smaller urban areas, such was the force of feeling, that nearby country houses were at risk, particularly those individuals who had been long-established as part of the political class. Anger in Poole, Dorset, was still fermenting even after news of the suppression of the Bristol riots and Encombe House, seat of the John Scott, 1st Earl of Eldon (b.1751 – d.1838), who had been loyal advisor to the Crown and Lord Chancellor, was now a target.

The riots at Bristol were quieted and a sufficient force fixed there, two troops of the 3rd Dragoons returned to their headquarters at Dorchester. This morning intelligence was received that a mob from Poole were intending to attack Lord Eldon’s place at Encombe, and also Corfe Castle. Mr Bond’s troop of Yeomanry were in consequence called out, and stationed on and about the bridge at Wareham, thus effectively guarding the only approach from Poole.

Mary Frampton, quoted from her journal (5 November 1831)

Nottingham

Nottingham in the early nineteenth century was described as ‘the worst slum in the Empire apart from Bombay’. Industrialisation had created an influx of workers, but local landowners – aristocratic and commoner alike – refused to release land for house building, forcing an increasing number of families into smaller and ever-worse accommodation. The expansion of the city was blocked to the west by the Duke’s Nottingham Park and Lord Middleton’s estate at Wollaton Hall, and to the east by Colwick parish which was largely owned by the Musters family of Colwick Hall. The north and south boundaries were ‘common’ land which was allocated by lottery to 250 burgessess and freeholders, who defended their rights to the arable land as fiercely as the larger landowners.

The rioters therefore had a number of targets, but their main ire was directed at the property the Duke of Newcastle, an ardent and active opponent of reform, who was also one of the most significant landowners in Nottinghamshire. He also controlled a number of rotten boroughs, responsible for returning fifteen MPs, who all followed the Duke’s direction.

Henry Pelham-Clinton, 4th Duke of Newcastle (1785-1851), was a man of firm views, often expressed in a loud voice. Even the Duke of Wellington, a man with his own trenchant brand of dogmatic hauteur, declared: ‘There never was such a fool.’. Unfortunately for the Duke of Newcastle, his role as one of the leaders of the opposition to the Reform Bill made him a totemic figure in the cast of characters targeted by those angry at the failure of the vote.

Having receiving the news of the vote on Saturday evening, the crowd broke a few shop windows but ‘the Mob dispersed on the appearance of the Military‘ (Ne C 5004 – Letter from Thomas Moore, High Sheriff of Nottingham, Nottingham, to Henry, 4th Duke of Newcastle under Lyne; 12 Oct. 1831).

Sunday was a day of rest. On Monday (10 Oct), a public meeting had been called by the Mayor, which passed off peacefully, However, that evening:

“a Mob collected and after committing a few acts of outrage in the Town proceeded to Colwick where they destroyed the furniture & attempted to burn Mr Muster’s House, in which to a certain extent they succeeded.”

Newcastle Collection, Ne C 5004

Colwick Hall, the first target, was the family home of Jack Musters, a local magistrate. Built by Jack’s father, John, in 1776 to designs by John Carr of York, the substantial house was ransacked and set alight, leaving it severely damaged. It was later restored but was sold in 1892 and became the site of Nottingham race course for many years and later turned into a hotel. Having successfully attacked Musters home, the mob, now fortified on his wine cellar, cried out: “to the Castle“.

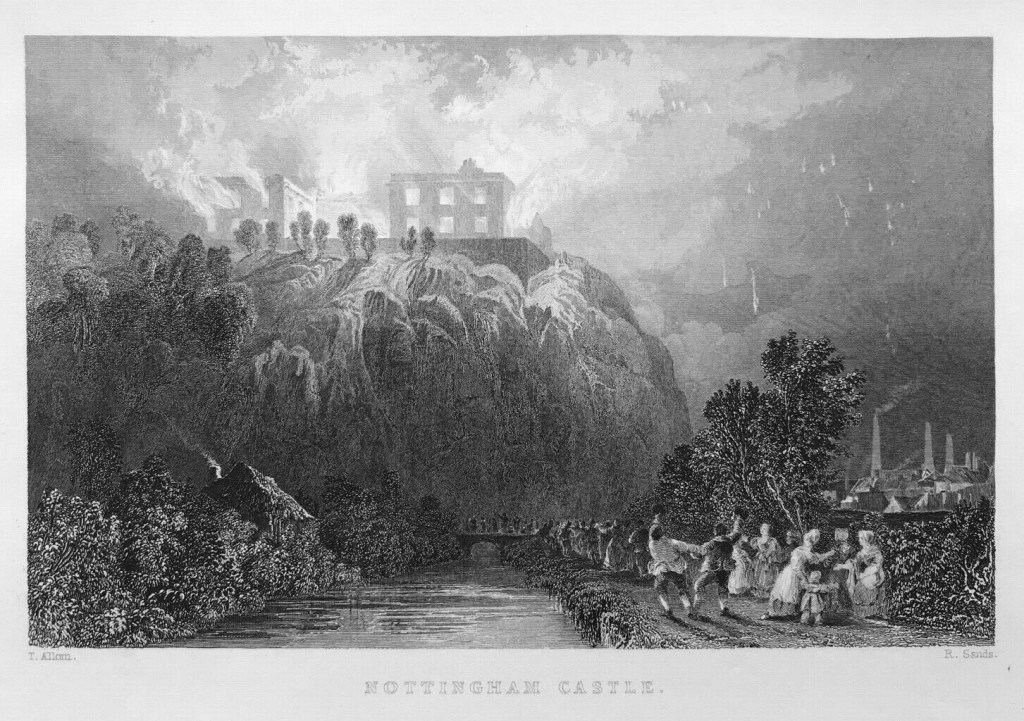

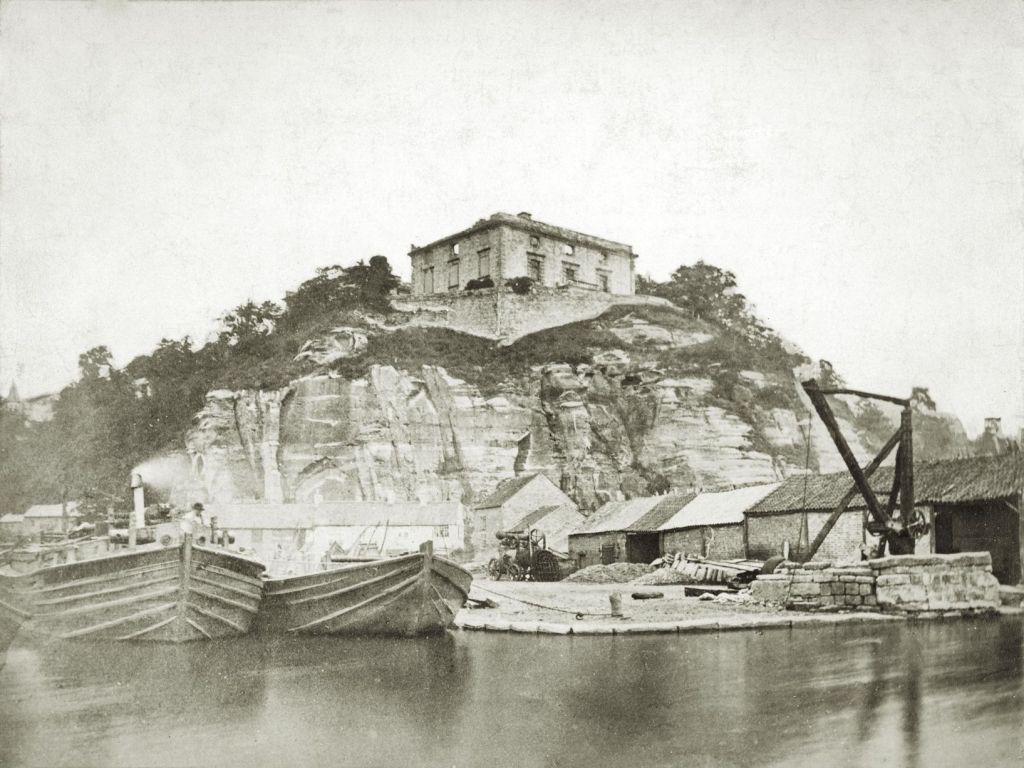

Dominating the city skyline since the first motte-and-bailey fortifications had been built in 1068, Nottingham Castle, had been a royal residence until around 1600. It was then held during the English Civil War (1642-1651) by the Parliamentarians who then razed it in 1651 to prevent it being used again. In 1674, William Cavendish, 1st Duke of Newcastle, purchased the castle and immediately began to build his palatial seat. The architect was originally thought to have been Samuel Marsh, a mason who had been working at Belvoir Castle, Chatsworth, (in the 1650s) and at Bolsover Castle (1660s).

However, the design of the palazzo, in a sophisticated and novel artisan mannerist style, is most likely to have been by the 1st Duke, himself (according to Colvin). The Duke died in 1676, before construction was complete. His will stated that the work was to be completed, using the £2,000 a year he left to fund the project, ‘according to the forme and modell thereof by me laid and designed.‘. The Castle represented a very personal manifestation of how he wished to be seen – and it retained this symbolism as the seat of the subsequent Dukes of Newcastle.

For the 4th Duke, an attack on his property must have seemed beyond the pale. The Castle had been unoccupied in recent years so it was guarded by just two or three servants. They were quickly overwhelmed, but unharmed, by the crowd, who numbered around six hundred.

[Having] forced their way past the lodge, [the crowd] poured in [the building] through a broken window, smashed the doors, and set about making a vast bonfire of this hated, if deserted, symbol.

Bryson, Emrys ‘Portrait of Nottingham’ – p.g. 95 (1983)

The mansion was ransacked and a substantial bonfire lit in the basement, which quickly created a fearsome blaze which consumed the entire house, the flames being visible for miles around.

About nine o’clock, the spectacle was awfully grand, and viewed from whatever point, the conflagration presented an exhibition such as seldom witnessed. The grand outline of the building remained entire whilst immense volumes of flames poured forth at the windows, and in some places were seen through the green foliage of the trees. Thousands of people thronged the Castle-yard and every spot that commanded a sight of the fire.

Between the hours of nine and ten, the conflagration had reached its height; the town was comparatively free from tumult, and thousands thronged the Castle-yard, to gaze with mingled feeling on the dreadfully novel spectacle.

Mercury; 15th October 1831

Meanwhile, despite the local knowledge that it was well-defended, a separate group had meanwhile started to make their way towards Wollaton Hall, the seat of the 6th Baron Middleton. He had been responsible for a substantial number of changes to the house, directed by Sir Jeffry Wyattville, which had created the imposing centrepiece to Lord Middleton’s estate which, to the rioters, represented another perceived aristocratic blocker on the expansion of Nottingham. The attack on Wollaton was thwarted when the mob were met on their way to the house by the Yeomanry. They engaged the mob, injuring some and capturing others, following which the remainder fled – though they later pelted them with rocks and bricks in an unsuccessful attempt to free the prisoners.

The Duke was still in London so updates came via letter. Thomas Moore, High Sheriff of Nottingham’s earlier correspondence continued:

“I regret to say that afterwards they proceeded to your Grace’s Castle which they completely destroyed”

A local newspaper, The Journal, reported that:

…[the] outer walls of this once splendid edifice are alone left standing, and we fear will remain an eternal monument of the fury of a misguided multitude.

Journal – 15th October 1831

As the light of Tuesday morning rose, the sight of the now gutted and smouldering castle met those looking up from the city streets.

In contrast to the defenceless Castle, the Duke had be most concerned about the mob attacking his main residence, Clumber Park. In letter written on behalf of his son, the Earl of Lincoln, who was at Clumber, he wrote:

‘…that he is in hourly expectation of an attack on Clumber House. the plate and pictures we have been engaged with removing today and we are pretty well provided with arms and ammunition…’

Ne C 5002 – Letter from Richard Hunt on behalf of Henry Pelham-Clinton, Earl of Lincoln, Clumber, Nottinghamshire, to J. Parkinson; 11 Oct. 1831

A further letter the next day to the Duke gave more details about the preparations at Clumber:

Information having been received that the mob at Nottingham, after totally destroying Nottingham Castle by their intended [sic] to proceed to Clumber, Lord Lincoln gave immediate directions for the removal of the Pictures into the Evidence Room and which has been done without any damage whatever, and the Plate is lodged safely in the cellar, a wall has been built in front of it, which is whitewashed so as to appear like the other walls of the cellar, and a shelf upon which are Bottles set so that no one but those in the secret (and they are few) could find the Plate.

The 24 pieces of cannon are loaded and placed effective situations in various parts of the House and about 150 men were stations with them having also about 150 muskets and large pistols.

Ne C 5010 – Letter from Mr. J. Parkinson, Clumber Park, Nottinghamshire, to Henry, 4th Duke of Newcastle under Lyne; 12 Oct. 1831

Thankfully, given the high likelihood of bloodshed, the mob never attacked Clumber itself and the Duke was able to come and take up residence on 13 October from where he issued various proclamations regarding the rioters and set about re-establishing [the old] order.

The Duke’s disdain for their protest can be seen in his subsequent claim against the City of Nottingham for £30,000 in damages (though the Duke would privately claim that ‘not that 60,000 would rebuild & reinstate the Castle’). In the end, the jury reached a verdict on only the second day and awarded him £21,000. Displeased, the burnt out shell was left deliberately unrestored to remind the people of Nottingham of their riotous behaviour and the Duke’s displeasure until 1872, when it was sold and restored as a museum and opened by the Prince of Wales in 1878.

Conclusion

The immediate political effect of the riots was, at best, limited. Certainly those who rioted were not those who would gain suffrage under any of the then proposals. What the riots did represent was an outpouring of rage against the property of the reactionaries in the upper echelons of society who used their political power to block reform, but also those in the merchant and middle classes who were seen to be protecting and enabling them. Perhaps the power of the riots was to create a convincing impression that revolution may be the outcome, if reforms continue to be blocked. The riots were certainly influential in persuading the King to back Earl Grey in his plans for reform.

Following this violent spasm of protest, remarkably, the country house was then to remain safe from targeted campaigns of destruction until the 20th-century. Part 3 in this series of articles examines how this changed and the effects it was to have.