In the fresh night air, they made their way across moorland and parkland towards a number of darkened country houses, their fierce determination matched only by their inexperience as ‘terrorists’. The flames from their arson attacks engulfing the country houses of their political opponents signalled a calculated escalation; attacks on property to further their cause.

Frustration is often at the root of violence and, without a release valve, the impulse to retaliate escalates. Property is inherently symbolic and can simultaneously embody beauty, power, wealth, status, but also hierarchy, division, oppression and domination.

This article looks specifically at instances where country houses suffered destruction as an outcome of organised violence. The targeting of country houses in the UK in peacetime in this way is rare but such bursts of architectural iconoclasm are not unknown and span centuries of anger. This was intended to be a short article, but it turns out that it will now be published in three parts as there’s a bit more than I thought. Each part will focus (mostly) on one violent campaign: one driven by religious differences, one political anger, and one democratic inequality.

For context though, let’s start with the two obvious campaigns which resulted in the destruction of country houses; the English Civil War and the Irish War of Independence.

English Civil War (1642-1651)

War has often led to tragic wholesale destruction. However, it’s worth noting that during the English Civil War, although it is estimated that between 150-200 country houses were destroyed (and many others were damaged), the destruction was broadly linked to military considerations such as the actual or potential use as a barracks or defensive structure, rather than wanton vandalism.

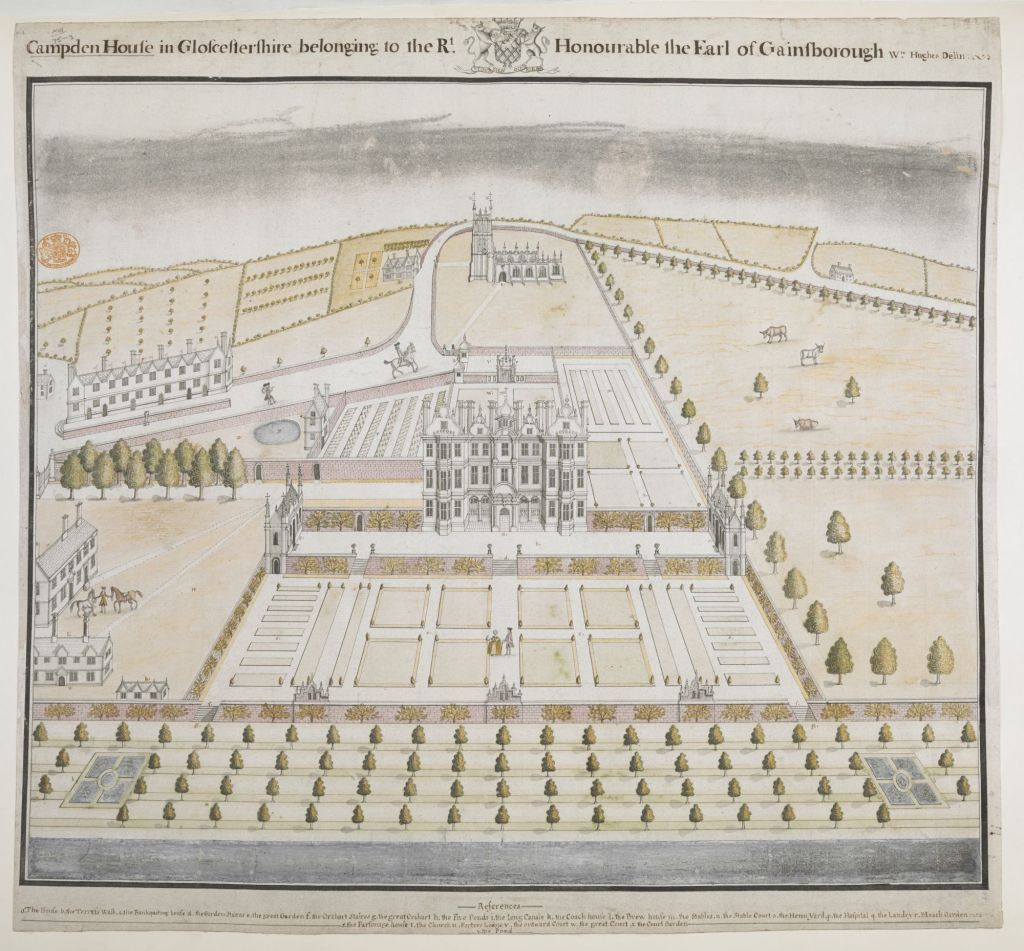

When the royalist Sir William Campion identified that Chilton House, Buckinghamshire might be used as a parliamentary garrison, he wrote ‘my fancy this morning did much envite mee to set fyre to the house’. Instead, Sir William was ordered to pull down the outer walls and remove the doors, leaving it intact but uninhabitable (c.f Besselsleigh, Oxfordshire). However, when, in 1645, the royalists withdrew from Campden House, Gloucestershire, they burnt it down to prevent any possible future use.

This controlled approach, for political and legal reasons, was evident on both sides. As the long-term intention was to occupy, rather than destroy, the orders to target attacks and undertake measured actions limited the authority of commanders to raze towns and buildings. To keep the common soldiers of both side in line, the orders issued to prevent indiscriminate destruction threatened transgressions with the death penalty.

Aesthetic considerations were also a factor. The activities of the parliamentarians were directed by the Committee of Both Kingdoms (1643-1649) which issued instructions that certain houses be protected as far as possible, including Burghley House, Cowdray, Chatsworth House, and Hardwick Hall. Specifically, in response to a request in 1646 for permission to burn down High Ercall House, Shropshire, the committee stated that, in general, it did not ‘think it fit that all houses whose situation or strength render them capable of being made garrisons should be pulled down. There would be then too many sad marks left of the calamity of this war.’.

Irish War of Independence

The most prominent example of an organised campaign of country house destruction is the sustained campaign in Ireland in relation to the struggle for independence.

Between 1919-1923, 275 houses were destroyed (Dooley, Terence – The Decline of the Big House in Ireland: A Study of Irish Landed Families. Dublin: Wolfhound Press, 2001) to deny the use of the houses as garrisons, or in symbolic reprisal; either as symbols of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy or for attacks by British forces. Professor Dooley and others such as The Irish Aesthete (Robert O’Byrne) have well-documented this campaign, and they have covered it far better than I could (e.g. ‘…it seems everything we love goes’: The burning of Castleshane, 15 February 1920‘).

Beyond these periods, the country house has been targeted in at least three distinct occasions; the first, a localised religious pogrom, but one which focused on destroying property, rather than lives.

The Birmingham Riots of 1791 (aka: the Priestley Riots)

Birmingham in the 18th-century was notoriously riotous. The people rose up in relation to high food prices (1766, 1782, 1796, 1800), and targeting religious minorities (Dissenters in 1714 and 1715, Quakers and Methodists in 1751 and 1759, and Catholics during the Gordon Riots in 1780). Into this febrile atmosphere, there was the usual tensions of the ages, which corruption, prejudice and alcohol could only exacerbate.

The swirling currents of international events often cause waves which break on distant shores. The French Revolution in 1789 caused deep concern in England across all levels of society, predictably more for the church and aristocracy. This led to heightened fears around activities which may be seen to sympathise with such radical ideas. For some, though, the radicalism aligned with their own intellectual spirit of curiosity; as willing to explore new political ideas as they were the physical world.

On 14 July 1791, in the Royal Hotel, Birmingham, a dinner was held by a group of the city’s prominent intellectuals, scientists and industrialists. Many were connected with the Lunar Society, an informal social club which met each full moon, whose membership encompassed a broad range of interests. Chief among them was science, and one of the leading members was Joseph Priestley (b.1733 – d.1804), a chemist perhaps best known as being credited with the discovery of oxygen.

Priestly was complex figure and combined his extensive scientific knowledge with a deeply-held Christianity and contentiously attempted to combine the two. He brought a scientific sense of discussion to theology, tolerating ideas other than his own, which led to his part in the founding of Unitarianism. Perhaps most controversially, he also was a strong supporter of the French Revolution.

Priestley, along with others, had organised the 14 July dinner to celebrate the storming of the Bastille, which marked the start of the French Revolution. The event was blamed as the cause of the riot, but in reality this was merely a pretence, for there had been a long-running friction between the established church and dissenters. Those attending the dinner had sensibly proposed the first toast to ‘Church & King’ to express their loyalty and had left some hours before. Priestley, speaking later, reported that:

“When the company met, a croud [sic] was assembled at the door, and some of them hissed, and shewed [sic] other marks of disapprobation, but no material violence was offered to any body. Mr. Keir, a member of the church of England, took the chair; and when they had dined, drank their toasts, and sung the songs which had been prepared for the occasion, they dispersed. This was about five o’clock, and the town remained quiet till about eight. It was evident, therefore, that the dinner was not the proper cause of the riot which followed: but that the mischief had been pre-concerted, and that this particular opportunity was laid hold of for the purpose.”

Whipped up by local agitators, who provided both incendiary pamphlets and alcohol, a mob arrived that evening at the Royal Hotel, eventually smashing every window. The crowd were persuaded to move on by the proprietor, Thomas Dadley, but, either as directed specifically or of their own volition, decided to target the places of worship, businesses, and houses of those Dissenters who had been attending the dinner, whose names had been published in local newspapers.

The riots are considered one of the most documented events in Birmingham history, with both sides producing their accounts, including ‘The riots at Birmingham, July, 1791. (An authentic account of the dreadful riots in Birmingham, occasioned by the celebration of the French Revolution, on the 14th of July)‘. Written in a tone which suggests disapproval of the actions of the mob, it also blames those attending the dinner for their apparent disloyalty to King and country. The follow account draws on this report for the factual elements of the account.

The mob moved on, their violence now destroying nearby religious meeting houses associated with Priestley. The local magistrate, who had been inciting or restraining the mob depending on the account, now realised that there was no controlling them. Their targets were now the Dissenter’s homes, both in the city, and in what was then the surrounding countryside (these areas having subsequently been engulfed by the growth of the city).

Thursday 14 July

The first country house to be targeted was Joseph Priestley’s in nearby Fair Hill (which is today, Sparkbrook), less than two miles from the Royal Hotel. A plaque affixed to the side of the 1960s house which currently occupies the site commemorates that this was once a place of renown. On learning that the mob was heading in their direction, Priestley and his wife fled. Their son William bravely remained, but the house and laboratory were ransacked and burnt, the content either stolen or destroyed, including ‘the most truly valuable and useful apparatus of philosophical instruments that perhaps any individual in this or any other country, was ever possessed of.’

The rioters then appear to have decided that this was a sufficient achievement for the day and dispersed – but their work was not yet complete and they met again the next day.

Friday 15 July

The rioters had now split themselves into two groups, one to target the Dissenters houses and property in Birmingham, whilst the second group formed raiding parties to target their country houses in the nearby areas.

On Friday 15 July, the destruction continued with Baskerville House, on Easy Hill (now Broad Street) being attacked around 2pm. As had become part of the modus operandi of the mob, they ransacked the house for valuables, food, and drink, and then set it alight. Unfortunately, several of the most inebriated attackers failed to escape the house as it was burnt and were killed.

At the same time, a separate group of rioters, descended on Bordesley Hall. It was rebuilt in grand style in 1757, replacing a nearby medieval moated manor house, for the button manufacturer and banker John Taylor who spent some £10,000 on his works. He had emparked 15 hectares of land and laid out an ornamental pool on the brook with an island, bridge, and grotto. Exotic shrubs and swans were imported to complete the scene. When the crowd arrived, ‘There five hundred pounds were offered them to desist, but to no purpose, for they immediately set fire to that beautiful mansion, which, together with its superb furniture, stables, offices, green-house, hot-house, etc. are reduced to a heap of ruins.’ (Matthews).

It was rebuilt but demolished in 1840 when the estate was sold off for housing development.

Saturday 16 July

As the violence moved into the third day, the pretence that this was just the frenzied actions of a spontaneous mob was clearly false as more houses were destroyed by groups of men and women, sent with specific intent.

‘The mob being now victorious, and heated with liquor, everything is dreaded’

A.B. Matthews’ ‘The riots at Birmingham, July, 1791, pg. 5

Their next target was the home of William Hutton, bookseller and paper warehouse owner, but also a significant figure in Birmingham history, having published the first history of the city in 1781. His success enabled him in 1769 to build a small country house called Red Hill House in Washwood Heath, approximately three miles from Temple Row.

He later recorded that, ‘The triumphant mob, at four in the morning, attacked my premises at Bennet’s Hill, and threw out the furniture I had tried to save. It was consumed in three fires, the marks of which remain, and the house expired in one vast blaze. The women were as alert as the men. One female, who had stolen some of the property, carried it home while the house was in flames; but returning, saw the coach-house and stables unhurt, and exclaimed, with the decisive tone of an Amazon, ‘Damn the coach-house, is not that down yet? We will not do our work by halves!’ she instantly brought a lighted faggot from the building, set fire to the coach-house, and reduced the whole to ashes.’

Meanwhile, back in Sparkbrook, where the ruins of Joseph Priestley’s house were probably still smouldering, the mob returned, marching on the substantial Sparkbrook House. Home to furniture retailer George Humphrys, ‘He had prepared for a vigorous defence, and would most certainly have been victorious, for he had none but rank cowards to contend with.’ (Hutton). It was reported that, ‘The people who demolished Mr. Humphrys’ house, laboured in as cool and orderly a manner as if they had been employed by the owner at so much per day.’ (Matthews).

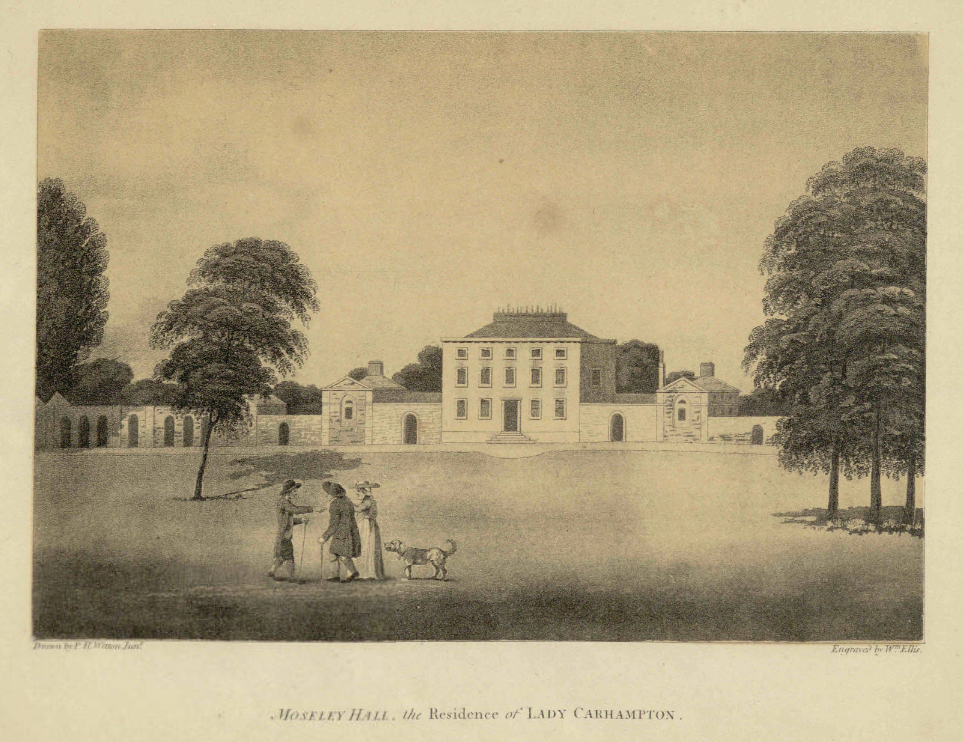

Their next target was Moseley Hall, also owned by John Taylor, whose other property, Bordesley Hall, had been burnt down the previous day. In a rare vignette of compassion, as Moseley Hall had been rented to the elderly dowager Lady Carhampton (mother of the Duchess of Cumberland), she was given a grace period to enable her belongings to be removed before the fire was started. Curiously, the mob offered genuine assistance to help her do so and protected her belongings in the four waggons it took to take them to safety.

‘The house was spacious; and the conflagration appeared from the town most tremendous. The fury of the mob being directed against this fine building, did not proceed from any hatred to the Lady, but because it was the property of Mr Taylor, whose other houses have been burnt down’

A.B. Matthews’ ‘The riots at Birmingham, July, 1791. pg. 7

Also razed as Kings Heath House, in King’s Heath (approx. four miles from Temple Row), owned by John Harwood. To the north-east, Wake Green House, in Wake Green, owned by Thomas Hawkes was similarly destroyed (though first having earlier sheltered Joseph Priestley as he fled the attack on his home).

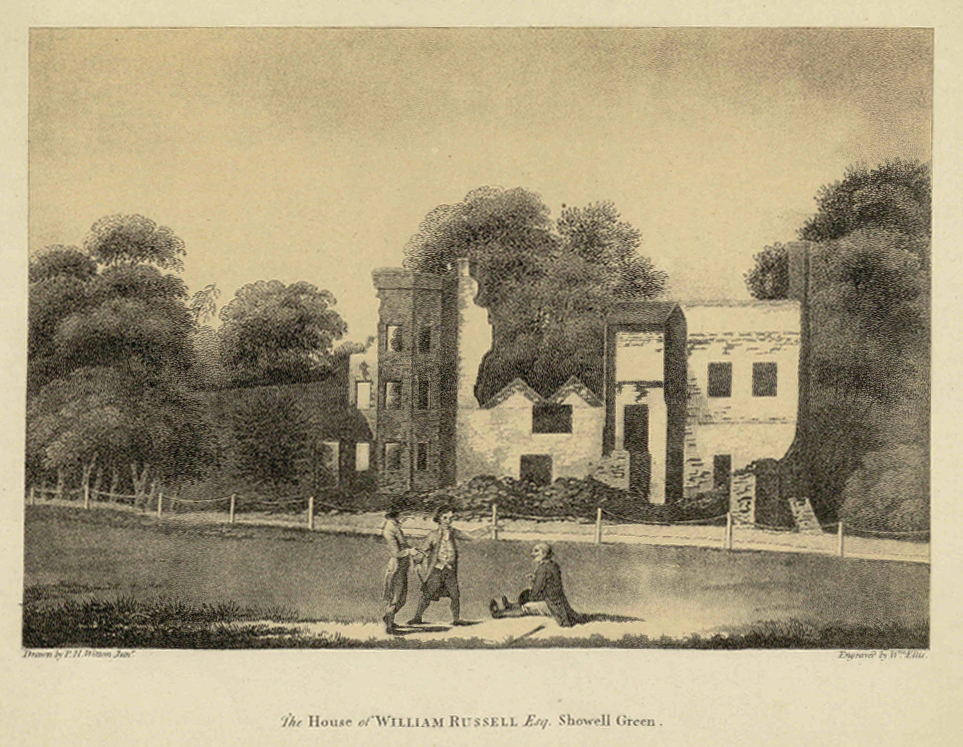

William Russells’ house was the final target of the day, though the family had left earlier in the day. William remained to face the mob, but it was claimed that ‘Some pamphlets, of an inflammatory nature, and a private printing press, being found in the house of Mr Russell, were the cause of its being burned.’. (Matthews)

Sunday 17 July

The mob was reported to now be around 2,000 strong. More were joining each hour, including ‘several thousand’ miners from Dudley, Woodside, and Wednesbury, with one fearful estimate that the numbers could, or had already, reached ten thousand. It was clear that the campaign was not just limited to country houses; all property of Dissenters was targeted, including town houses, commercial premises, meeting houses, and mills. By now, those seeking to stop the violence had called on the military to oppose the mobs as they feared that the entire town and others nearby, including Kidderminster, were going to be destroyed, but also that costs of repairs for existing damage would lead to significant tax increases.

The pace of destruction now slowed and the only country houses targeted (but not destroyed) were Ladywood House, the home of Harry Hunt, and Hay Hall at Hay Mills, the home of Joseph Smith.

Edgbaston Hall was the home of Dr William Withering, the noted botanist, who, though not a Dissenter, was known to be a friend of Priestley, therefore his house became of interest to the mob. Luckily for him, his staff were able to delay the mob’s attacks until 64 men of the 15th Regiment of Dragoons arrived from Nottingham to successfully oppose the rioters.

Total losses from the attacks were estimated at £80,000 (approximately £144m on an income value calculation), of which, John Taylor portion was the most significant, totalling £25,000 (approximately £45m – income value).

Monday 18 July

With soldiers continually arriving in Birmingham, the scene became even more tense as the rioters had by now looted several sword factories and were partially armed. In skirmishes, the rioters had actually successfully defended themselves against the soldiers, who retreated to await reinforcements. Later, with the addition of significant numbers of troops, the will of the mob was checked – or, as it was put in a rather understated report:

‘…the magistrates, and some of the principal gentleman of the neighbourhood, explained to them the illegality of their proceedings, and informed them of the immediate and subsequent consequences thereof, which had the desired effect; they dispersed in several small parties, and left the town in possession of its former tranquillity.’

With the riot over, the good townsfolk of Birmingham went back to their usual lives. Protected by the same establishment who had instigated the violence, there appears to have been few consequences for those involved beyond the hangovers and deaths by misadventure and violence, which accounted for some sixty rioters. For those targeted, their lives were forever changed. Many left whilst some rebuilt their lives – but the shadow of violence is one which clouds a life long after it has passed. Joseph Priestley never lived in Birmingham again, moving first to London, before settling in Pennsylvania for the last ten years of his life.

So ended one of the most organised and destructive spasms of peacetime violence against country houses in the UK. The country house was to remain at peace until four decades later, political (rather than religious) anger was to again place them in danger.

Conclusion

Remarkably, the country house was then to remain almost sacrosanct, safe from targeted campaigns of destruction for another half-century until, again, anger spurred action. Part II examines this second outbreak of violence and the country houses it touched.

Further reading

- Panic on the Streets of Birmingham: July, 1791 (Secret Library Leeds)

- The Birmingham Riots 1791 (William Dargue – A History of BIRMINGHAM Places & Placenames from A to Y)

- ‘The riots at Birmingham, July, 1791. (An authentic account of the dreadful riots in Birmingham, occasioned by the celebration of the French Revolution, on the 14th of July, 1791, etc. Views of the ruins of the principal houses destroyed during the riots at Birmingham. Vues des ruines, etc’ / [preface by A. B. Matthews] (Birmingham : Arthur Bache Matthews, 1863).