In a time before widespread literacy, a physical representation of what was intended to be built was a powerful aide to help ensure that the vision of the architect became the physical reality crafted by the builder. Yet, the architectural model was more than this. Evolving from being a functional tool, it became an aspirational marketing device to demonstrate the proposed scheme but also as a three-dimensional business card for the architect and striking conversational piece for the wealthy patron who would possess both the miniature fantasy and the full-size reality of the design of their country house.

The role of the architectural model can be traced back to the earliest buildings, particularly the devotional and religious. Some of the oldest were found in Egyptian tombs, dating back over four thousand years, and represented functional spaces which may be required such as granaries or gardens. Later they were often displayed as a record of the beneficence of the donor (rather than skill of an architect), they appear in paintings or decorations being held as offerings (such as the 10th-century Vestibule Mosaic showing Justinian presenting the Hagia Sophia to Mary and Christ), or carved into their funerary monuments or other personal iconography such as portraits; all undoubtedly a handy aide-memoire to St Peter, come the reckoning on Judgement Day.

The creation of models of new buildings is recorded in the 15th-century with the renowned architect and theoretician Leon Battista Alberti (b.1402 – d.1472), stating that,

‘I always recommend the ancient builders’ practice by which not only drawings and pictures but also wooden models are made, so that the projected work can be considered and reconsidered, with the counsel of experts, in its whole and in all its parts.’

The fashion for the creation of architectural models as objects for study and decoration was one which grew with the interest and wider participation in what became known as the Grand Tour, particularly from the 1760s. As wealthy young men would embark on extended study (and, if we’re honest, pleasure) tours of the Mediterranean and Middle East, so too did their desire to bring back a tangible memory of their time to display as a marker of their cultural and worldly sophistication.

Cork established itself as a popular material for the crafting of models of ancient ruins as it was intrinsically similar in its native form to the weathered appearance of the stones it was shaped to resemble. Light and easy to transport, it is easy to imagine that many hundreds of these were shipped back to country houses back in the UK as a reminder and an inspiration. It is interesting to speculate how influential these romantically ruinous models were on the nascent Picturesque movement of the 1780s. The models may have generated not only new buildings but also the incorporation of existing ruins into new landscapes or the building of new ‘old’ ones too, energised by having at hand aesthetically compatible examples, steeped in irregularity and showing the forces of nature providing the finishing touches to the works of man.

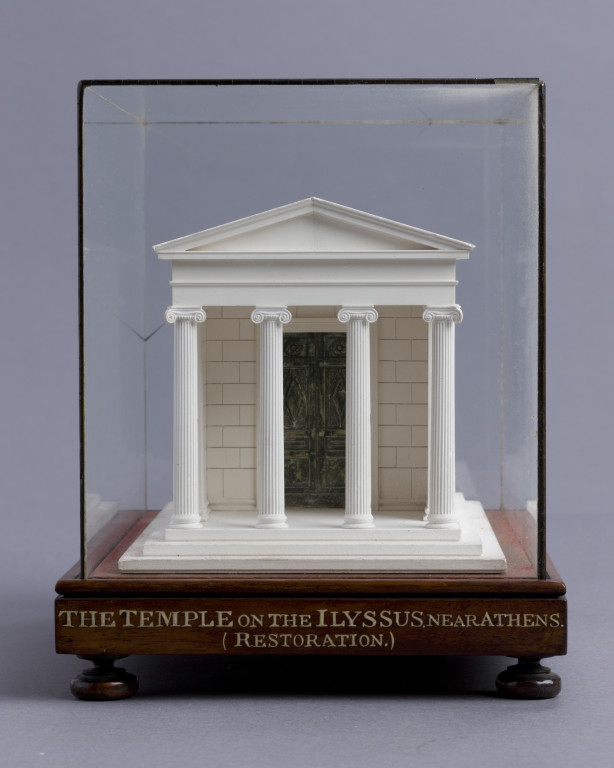

For those who wished to show a more idealised representation of architectural purity, clearly the imprecise renderings of cork were not going to match their visions. In the 1780s, to demonstrate the beauty of the finer details of the classical world, entirely white, finely crafted ‘Plaster of Paris’ models started to be created. Almost of these are thought to be the work of two French modellists, Jean-Pierre Fouquet (b.1752 – d.1829) and his son Francois (b.1787 – d.1870), who were based in Paris, trading as Fouquet et Fils.1 For architects, these models presented an alternative version of reality, one which enabled them to present their own schemes in a favourable context to the works of the ancient world.

Beyond the decorative role, the models were also naturally didactic; their representations of the ruins of the ancient world creating opportunities to teach those who would not otherwise be able to travel to see them. Of those who embraced this approach, the most prominent and inventive was Sir John Soane. His collection was one of the largest but who was also able to use them as inspiration, as teaching aids to his pupils and marketing tool for those who visited his home/studio at Lincoln’s Inn Fields in London, where they can still be seen today in the restored model gallery.

“Many of the most serious disappointments that attend those who build would be avoided if models were previously made of the edifices proposed to be raised. No building – at least none of considerable size or consequence – should be begun until a correct and detailed model of all its parts has been made.”

– Sir John Soane (Royal Academy lecture, 1815)

Soane was drawing on his own experience but what had clearly been a well-established technique within the building trade and architectural profession – but just how frequently were these model houses created as part of the commissioning process? The key challenge is that so few are known to have survived that it’s difficult to draw broad conclusions from such a small selection. However, it is instructive to take a tour of a sample to see the range and skills deployed by architects and craftsmen to not only convince the patron but also to explore proposed designs at a stage when corrections were far easier to make.

One of the earliest known examples (and my thanks to Jeremy Musson for bringing it to my attention), is a beautifully detailed model of Quidenham Hall, Norfolk, dating from the early 1600s. The manor was bought by the Holland family from in 1572 and the model was created for the construction of the first house in 1606 – probably in the same year, as it would act as the visual guide for the builders and masons.

In the context of a less-educated age, the value of the model to the build process becomes more apparent, particularly for more complex designs such as Quidenham, with its detailed elevations including procession, recession, bows, pediments, crenellations, stepped gables, and chimneys. A feature of the architectural models is that they can be explored, with the house dissembling either horizontally including the exterior walls, or just the interior floors, enabling a ‘fly-through’ so beloved of modern property programmes. Clearly, being able to visualise the interior in relation to the exterior provided clarity as to the relationship between the designs for the rooms and their physical placement.

Quidenham Hall was subsequently extensively remodelled in the 18th-century with additional wings and the refacing of the entire house in a unifying neo-classical design. For us today, one value which was unexpected in the original construction of the model is that it allows us to know with a high degree of certainty what the original house looked like, despite these changes.

The degree of craftsmanship which was invested in the models is perhaps best shown in the remarkable model of Nicholas Hawksmoor’s masterpiece, Easton Neston, in Northamptonshire. Dating from 1689, it is considered one of the most important models to have survived, due not only to the superb craftsmanship but also because it relates to the design of a house regarded as central to the development of the Anglo-Baroque aesthetic. The model was bought for £180,550 in 2005 when Baron Hesketh sold the contents and house and is now in the RIBA Architecture Study Rooms at the V&A in London.

Sir John Soane’s designs for Tyringham Hall, Buckinghamshire, are a particularly instructive example as model, drawings and house (the latter with minor later alterations) survive and can therefore be readily compared. Commissioned by the banker William Praed, the house took five years to build from 1793 to 1798, with the model being created in mahogany c.1793-1794 by Joseph Parkins, a joiner working on the project. This sophisticated approach of thoughtful, inventive but ultimately practical designs, high-quality presentation watercolours by Joseph Gandy, and equally polished miniature evocations show the exemplary professionalism of Soane and why he was one of the leading architects of the era and held in such high regard.

A later example was the model created for Pyrgo Park, Essex (demolished c.1940). The house was built for Robert Field, who had inherited a largely derelict Tudor house and estate from his brother in 1836. The remains of the old house were demolished in 1851-52 and a new house built on the same site to a design commissioned from Thomas Allason (b.1790 – d.1852). In light of the architect’s death, in the same year as construction on the new house was due to start, the creation of the model in 1851, now held in the RIBA Collection, would have enabled the work to continue and for a house, faithful to the architect’s design, to be created.

Another architect to use models was George Devey (b.1820 – d. 1896) who produced them as a matter of course when proposing a design to a client. The distinctive feature of Devey’s models, produced by a dedicated, in-house modeller who was ‘in constant work’, was their scale, being produced small enough to fit in custom, briefcase-sized boxes. These often beautiful models allowed Devey to dispense with creating perspective drawings, producing only elevations and plans, which were combined with the physical miniature they would see in front of them.

Two more models are worthy of note due to their size and beautiful detailing. One of the tallest was for Fonthill Abbey, Wiltshire, the vast Gothic edifice built for William Beckford constructed between 1786-1807. The model was notable not only for its scale (built at a ratio of 1 inch to 10 feet), but also for its own evolutionary construction with the model corresponding in part to the earlier designs from 1799, but overall the composition is similar to the engravings from the 1820s. The irony is that this model, built of fragile card, survived more completely than the ill-fated abbey itself.

Perhaps the most beautiful and largest is the proposed model for a new palace in Richmond, Surrey, designed by William Kent for King George II and Queen Caroline in 1735. Created in pearwood, the model is nearly two and half metres long and is exquisitely detailed, as one would expect of a presentation model to be shown to royalty.

Clearly there is a long history of the use of models, with examples for houses both large and small from multiple notable architects and other evidence that these models were not an uncommon element in the design and construction of country houses. So, why are so few known to have survived? Without more primary, documentary evidence, conclusions necessarily have to be somewhat conjectural.

Some study has been made of architectural models, particularly by Professor John Wilton-Ely, who has stated that although frequently used, they were less used by the end of the eighteenth-century. He also highlights that whilst models found favour with some architects, such as Soane, others such as William Chambers only used them occasionally, Wyatt only appears to have used it Fonthill and Longford Castle, Wiltshire, and that there are no known instances of their use by Robert Adam.

Additionally, one reason so few have survived is their role in the actual construction process; the frequent use on-site and the high-level of wear-and-tear likely to result from such treatment meant that those made from more fragile materials such as plaster or card were always at risk of being worn out and discarded.

For those which survived, their bulky nature would always be a factor in determining whether someone not only had the inclination but also the space to store them. Minutes and correspondence from within the Victoria & Albert Museum shows the ascending and waning fortunes of architectural models. When the V&A first opened (called then, the Museum of Construction), models were given prominent billing and display space – though of the seventy-plus identified2 from the hundred known in the collection, only one is a house, surprisingly dating from 1936. The lack of country houses is stark, reflecting a level of institutional disinterest from the outset and over the lifetime of the collection. Cumbersome and unloved, the collection was removed from display in 1888 and put into store. After ownership was passed unenthusiastically between the various museums, the V&A reluctantly took them in 1916 (‘The items do not for the most part appear to be very desirable for us, either for exhibition or reserve‘) with some being selected for disposal, the minutes recording ‘their cremation‘.

Perhaps the most intriguing method of survival is the most charming – their use as dolls houses. Once the model had served its purpose in design and construction, and perhaps served time as a conversation piece, one can easily imagine the children of the house being given a chance to recreate their lives in miniature. They also would serve as training for one day managing a country house of their own. So if you, or a relative, has an antique but surprisingly good quality or familiar looking dolls house in the attic, take a closer look…!

Perhaps the most impressive (and remarkable) surviving example is that of Melton Constable Hall, Norfolk, dating from the 1660s. The architect of the now grade-I listed house is unconfirmed, particularly as there are no known drawings, but it is thought that the owner, Sir Jacob Astley, may have designed it himself. In such circumstances, the building of a model would have been a prudent step, both in confirming that his design was fit-for-purpose and for subsequent use during construction. The model of the house was then passed through generations of the Astley family children before being donated to the Norfolk Museum Service.

Another dolls house, this time at Greystoke Castle in Cumbria, was discovered to be a proposed eighteenth-century design for the enlargement of the pele tower. Much of the work at Greystoke was completed by Anthony Salvin (b.1799 – d.1881) so it is possible that this an example of another architect using models as part of the process.

Today, the architectural model exists but as a method of celebration and display. The model is less a functional representation of what will be and instead is a now a mechanism for the long-term appreciation of the finished building as sculpture. It is curious to note that the model has moved from the purpose of remembrance to aspiration and back to the recreation of what has been lost. The sophistication of modern digital rendering has sadly removed the need for the model to help those commissioning a country house to visualise it. However, in this we have have lost the physicality of the form and the sheer pleasure of the craftsmanship of a country house model; idealised but as yet unrealised.

Known complete models of houses

Do you know of any others? If so, please add a comment with details.

Summary list of examples (architect name and current location of the the model, in brackets, if either are known)

- Butterton House, Staffordshire (Soane, Sir John Soane Museum)

- Greystoke Castle, Cumbria (unknown – possible Salvin, assumed to be at Greystoke Castle)

- Longford Castle, Wiltshire (James Wyatt, Longford Castle)

- Model for a proposed villa – version A, Acton, Middlesex (Soane, Sir John Soane Museum)

- Melton Constable Hall, Norfolk (Astley/Jacobs, Gressenhall Farm and Workhouse)

- Quidenham Hall, Suffolk (unknown, Norwich Museum Service)

- Tyringham Hall, Buckinghamshire (Soane, Sir John Soane Museum)

- Model for proposed new palace for Richmond, Surrey (William Kent, Royal Collection)

References

1 – ‘Plaster Casts: Making, Collecting and Displaying from Classical Antiquity to the Present’ – Rune Frederiksen, Eckart Marchand (Walter de Gruyter, 27 Sep 2010)

2 – ‘Inside Outside: Changing Attitudes Towards Architectural Models in the Museums at South Kensington’ – Leslie, Fiona, Architectural History, 47 (2004), pp. 159–200

Further reading

- Architectural Models in the V&A and RIBA Collections

- Models of perfection – Meticulously replicated buildings are proving popular commissions to commemorate special occasions or treasured memories. Clive Aslet talks to three master craftsmen about their very individual techniques