Slowly, then suddenly, many estates grew silent. Carriages no longer clattered down the drives. Entrance halls no longer echoed to voices. Kitchens went cold. Staff quarters were emptied. Then, the contents were sent to the auctioneers. Finally, the house was broken apart; hammers and pickaxes the new sounds as hundreds of years of history were reduced to rubble.

One key questions which architectural historians have been trying to answer for a number of years is just how many UK country houses have been lost? The answer, for now, is over three thousand. Each was a world on its own, but also part of the complex jigsaw of our national heritage.

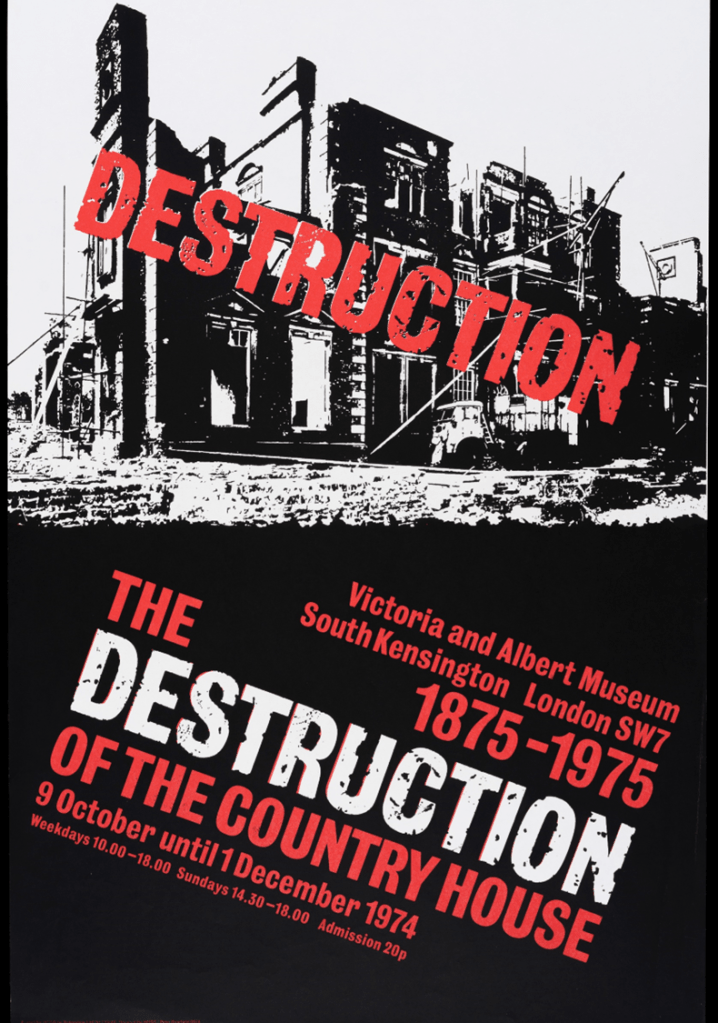

The genesis for this area of research was ‘The Destruction of the Country House‘ exhibition, which ran from 9 October – 1 December 1974 at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. I have written about it on a number of occasions so if you would like more insights into it, you can read my article on the 40th anniversary or my reflections on the 50th anniversary.

The position of the landed elites was considered the bedrock of society. The families provided political leadership, social aspiration, and were the centre of the local economy through their employment and expenditure. Land ownership was the passport to this elite status; the open market a safety valve which enabled ‘new money’ to mix with the old, to want to emulate them rather than remove them. This allowed new families to fluidly move up from merely wealthy to established gentry or nobility. After a few generations, the land functioned as an older form of ‘green-washing’, the verdant parkland obscuring where the family had started. Within a few short centuries (though sometimes it was just decades), they had become the elite.

However, the first half of the twentieth century was, for the owner of these large houses, often financially, socially, and politically challenging. The repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846, which opened our markets to cheaper overseas produce, combined with the agricultural depressions of the latter-half of the nineteenth century, had undermined many of the assumptions about the financing of the country house. As debts grew, so the stark financial reality of the situation they were in began to dawn. For many, the path to recovery seemed to be to sell non-core assets such as artworks or outlying estates and hope that this would tide them over until their incomes, usually agricultural, recovered. For those who sold their land early and invested in the stock market, the crash of 1929, was another blow to their planning. As is so often the case, the markets remained against them longer than they could remain solvent.

When Aldous Huxley published his first novel, ‘Crome Yellow‘, in 1921, the challenge to the country house was already significant enough to feature as the fate of the imaginary Gobley Great Park;

‘A stately Georgian pile, with a façade sixteen windows wide; parterres in the foreground; huge, smooth lawns receding out of the picture to right and left. Ten more years of the hard times and Gobley, and all its peers, will be deserted and decaying. Fifty years, and the countryside will know the old landmarks no more. They will have vanished as the monasteries vanished before them.’.

Thankfully, Huxley’s apocalyptic vision wasn’t fully to come to pass. However, from the relatively low levels of losses in the nineteenth-century, the twentieth-century would bring decade after decade of destruction. It’s worth remembering that this was largely a crisis of the country house, not the wider estate. The land was considered more valuable as an income-generating asset and for the social prestige it conferred. Without the expense of the house – the maintenance, the staff, the general running costs – so the income was better able to meet their expenditures. Mr Micawber would be beaming with pride.

So, when seeking to bring their expenditure within the available income, the house was considered a necessary sacrifice. And with so many other families also facing a similar situation, the loss of any one house would be obscured by the loss of so many others. The problem with simple data is that it belies the dramatic local impact the loss of a house would have been. The country house and its estate embodied the idea of stability. The idea of a family owning the house and land and passing it down through the generations was – and arguably still is – embedded firmly in our national psyche, even if the family did change every few hundred years. The key difference in the twentieth-century was that there was often no other family to take their place.

In this dark era, houses languished on the market. This was often evidenced by adverts for the same properties appearing with sad regularity in magazines such as Country Life. It brought reminders of the increasing threats to the established order of the countryside into the drawing rooms and libraries of those most at risk.

Each week, beyond the adverts in Country Life, ‘The Estate Market’ page offered a running commentary on the changes. For example, the headline for that page on May 5th 1922, was stark: ‘Demand for small properties’, with the opening paragraph stating, ‘The brightest section of the market is that in which the smaller properties are dealt with…’. Coverage includes the sale of Sudbourne Hall, Suffolk, saying it had sold with 500 acres, having first been offered as a whole but failing to find a buyer, it had been split up. The house was later demolished in 1953.

Another paragraph is headed ‘Mansions as sanatoria’ and writes approvingly of how Lords Londonderry and Boyne have both ‘generously offered’ Seaham Hall and Brancepeth Castle respectively for ‘hospital purposes’. Specifically, it states that Seaham Hall ‘…has had to be closed in consequence of taxation and the heavy cost of upkeep.’ (it survived and is now a hotel). It also mentions that Rendlesham Hall, Suffolk, has been sold for use as a ‘…retreat for drug-addicts and inebriates…’. It was also later demolished in 1949.

During the nineteenth-century, the available data shows that there were fewer losses; approximately one a year. However, when considering the data, there are a few caveats to remember. Critically, the data for the nineteenth-century is thinner than the twentieth-century. Fewer books had been produced, research was sparse, and even confirming if a property was of sufficient stature to be classed as a country house is sometimes challenging. Fire and replacement by a new house were two of the most common reasons.

So how many have been lost?

Quoted in The Daily Telegraph magazine in 2007, the leading country house historian of the lost houses, the late John Harris, said that:

‘At the time [before the V&A exhibition], we reckoned that about 750 houses [in the UK] had been pulled down between 1880 and 1970. Now we know it’s about 1,800.’1

Sadly, John’s estimate was still too low – 1,800 doesn’t even cover England alone.

The gazetteer at the back of ‘The Destruction of the Country House‘ exhibition catalogue listed a total of 1,099 houses (740 for England, 313 Scotland, 46 Wales, with NI not included). This list had been compiled by John, Marcus Binney, and another researcher, Peter Reid, and explicitly stated it was not exhaustive. The total for England was updated with the publication in 2002 of ‘England’s Lost Houses‘ by Giles Worsley which added 445, to total 1,185 for England. However, Ian Gow’s ‘Scotland’s Lost Houses‘ in 2006 listed only 308 (5 fewer than before) but also included examples of houses in cities (which I have excluded from that total).

The task of taking the ground-breaking earlier research forward and to resurrect the memory of these otherwise obscured houses, has now been taken up by amateur enthusiasts, supported by the invaluable work of historians who have focused on specific areas. I started researching the English lost houses in 2006, compiling what I hoped would become the most comprehensive record. All the details, including detailed histories and thousands of images, are shared on the Lost Heritage website.

Using the same model, this was followed over the years by Dr Alastair Disley for Scotland, Dr Mark Baker for Wales, and Andrew Triggs for Northern Ireland (he also took on the much larger task of the Republic of Ireland).

The scorecard of architectural losses

Each of these personal efforts has significantly increased the totals of lost houses with Scotland now standing at 545 (Disley), 390 for Wales (Baker), and 100 for Northern Ireland (Triggs – a particular achievement as they hadn’t been tallied previously).

The total number of lost houses for England alone has now exceeded John Harris’ original estimate for the whole of UK, having reached 2,019 (as at November 2024).

Overall, we can be confident that the number of UK country houses lost since 1800 now totals a remarkable 3,054.

Why does this matter? These houses and their particularly grand and hierarchical era and way of living has gone. It died, not in our leafy lanes, but in the battles and social change of the World Wars. The changes forced an evolution – and in that process, there are winners and losers. The tragedy was that the losers were often not inherently weaker houses, and in so many cases, they were some of the most interesting and significant. Beyond the random losses from fire and environmental causes, often what determined whether a house survived was their owners and their circumstances. For some, they were determined to ensure that the houses were reborn, albeit in a new way of living. For others, they were equally determined that that they would not pass what they saw as a burden to another generation.

In the specific losses to a family, and a locality, and to our architectural heritage, they were to be lamented. But in all of them, they possessed something of our shared heritage, and their loss, and the losses of the future, are pieces of the national jigsaw of our identity. As Simon Jenkins said, ‘Through them we hear the echo of our collective selves – and remember who we are.’2. We remember these parts of our history through the memory of these houses, and the roles they played in the life of our nation, both locally and nationally.

Request for help

If anyone has any further information on the lost country houses of England – either history, dates for losses, or family photos or recollections – please do contact me.

References:

1 – Campbell, Sophie, ‘Brideshead Detonated’ Telegraph Magazine, 20/01/2007

2 – Jenkins, Simon, ‘England’s Thousand Best Houses‘ (Penguin, 2004), vii