The analogy between language and architecture is one that has often been made, particularly as fluency is the key measure of success in both fields. An immature architect can make elementary mistakes with the grammar of a building style as much as any tourist abroad can when ordering dinner. In most cases, both novice architect and linguist can be understood but when compared to the more experienced practitioner, skill and mastery come sharply into relief. Such a lesson by a master architectural linguist has just been launched on the market; The Salutation, in Sandwich, Kent; a beautiful piece of poetry which demonstrates the fluency of the architect in the language of Classicism.

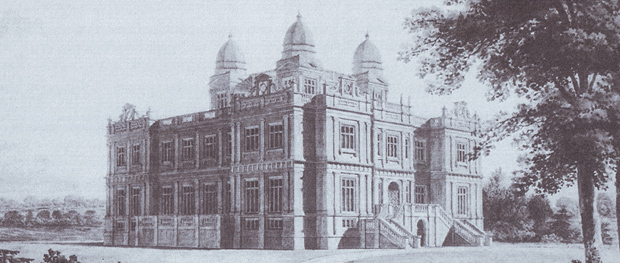

Lutyens’ career can largely be seen in three phases; the early years of the ‘Surrey-Tudor’, which evolved into the middle ‘Arts & Crafts’, and then the divergence into the bold ‘Classical’, and its particular variant, ‘Edwardian Baroque’. That last switch can be seen quite dramatically in the brilliant Heathcote, Yorkshire, built 1906, where Lutyens playfully adopted and adapted the Classical motifs and style of Palladio and Scammozzi to create a wonderfully detailed villa, rich in style and quite unlike his previous work. After the exuberance of Heathcote (which annoyed Pevsner, who although he commented that it was ‘Only a villa, but how grand the treatment!‘, also dismissed features such as the pilasters which ‘disappear’ into the continuous rustication (see ground floor either side of the windows) as ‘silly tricks‘). On a side note; Heathcote recently sold having previously been bought by a developer/vandal who wished to split the house into two, thus ruining Lutyens’ interior planning – fingers crossed the new owner is sympathetic to this wonderful house.

Lutyens was, of course, part of a longer tradition starting with the first English classical architects practising around the time of Sir Christopher Wren in the mid-17th Century including Hugh May, William Samwell, and Roger Pratt. These pioneers displayed a similar skill in Anglo-Classicism producing buildings such as Cassiobury House (May), the first Eaton Hall (Samwell) and the revolutionary Coleshill (Pratt). Classicism has long had a place in British architecture, despite other fashions, and has shown its versatility in being used for all sizes of house, from palaces to the smaller country retreat – and it was in this latter requirement that Lutyens was commissioned to build The Salutation.

Located on the site of an old inn of the same name, it was built in 1911-12 in the Queen Anne style as a retreat for Gaspard Farrer, a partner in Barings Bank, and his two bachelor brothers. Lutyens’ clients were typically those who had made money in the decades either side of 1900; that high-point of the country-house lifestyle when staff, materials and labour were relatively cheap. If there is a ‘criticism’ of Lutyens it’s his generosity with regards to space with hallways, alcoves, and large staircases, such as at The Salutation where an extended landing serves as an overflow from the library. Yet, each space serves a purpose in the plan, typically framing views along axes or as part of a route to the principal rooms which Lutyens often incorporated into houses.

The exterior of the house is a smaller derivation of his earlier and much grander Great Maytham, built 1910, for the Liberal MP, H.J. Tennant. Following the exuberance of Heathcote (which most commentators seem to think came very close to pomposity), Lutyens took a more restrained path through Classicism (compared say, to Richard Norman Shaw at Bryanston House for Viscount Portman) and Great Maytham can be seen as a larger version of Samwell’s Eaton Hall, built 1675, or the smaller Puslinch in Devon, built 1720, with the latter showing clear similarities with The Salutation.

The plan of The Salutation is based on the Palladian 3×3 grid but, importantly, Lutyens is able to adapt and amend this without losing the beauty of the proportions. Gavin Stamp comments that, for Lutyens, his houses were ‘essentially romantic creations; that is, their form is determined by a picture in the architect’s mind‘ and another writer H.S. Goodhart-Rendel compared his ability to that of Wren in that they both had ‘the sculptor’s capacity of making beautiful shapes‘. Country Life magazine said that it was a ‘dazzlingly suave yet restrained reinterpretation of the old Georgian idiom‘. It was this ability to combine a profound understanding of the Classical rules of architecture with originality which marked Lutyens out as one of the great architects.

To be given a measure of the importance the house, in 1950, it was the first 20th-century building to be given a Grade-I listing. However, The Salutation suffered in the later 20th-century with the 1980s a particularly difficult time. Repeated attempts by developers were made to either split those graceful internal spaces into apartments or simply demolish it entirely and build on the 3-acre site, over which Lutyens (and possibly his long-term collaborator Gertrude Jekyll) had spent so much time and care crafting.

Salvation for The Salutation came in the form of Dominic and Stephanie Parker who bought it in 2004 for £2.6m and have subsequently spent £3m on its restoration and who now run it as a luxury B&B. Now for sale at £4.5m, for someone with the budget, this could again be a superb home; combining the finest elements of the last boom of the country villa, designed by one of the greatest architects Britain has produced. For the rest of us, if you’d like to see and experience staying in one of Lutyens finest small houses, I’d suggest booking soon.

———————————————————-

Sale particulars: ‘The Salutation‘ [Knight Frank]

If you’d like to stay; you can book through their website: ‘The Salutation‘

Video of Mr Parker talking about his decision to buy: ‘The Salutation was ‘like finding a diamond in a river‘ [2009, Kent Online]

Watch the Parker’s competing in a B&B TV competition: ‘Four in a bed‘ [Channel 4]

For more on Lutyens, I recommend Gavin Stamp’s ‘Edwin Lutyens Country Houses‘ [Amazon]

Support the legacy: ‘Lutyens Trust‘

Listing description: ‘The Salutation‘ [British Listed Buildings]