Below is the first of two exclusive articles marking the 50th anniversary. This piece delves into the inception of the exhibition and offers some additional reflections. The next article, to be published shortly, will provide an eagerly anticipated update on current research efforts to identify all the lost houses, featuring some significant news on the total count.

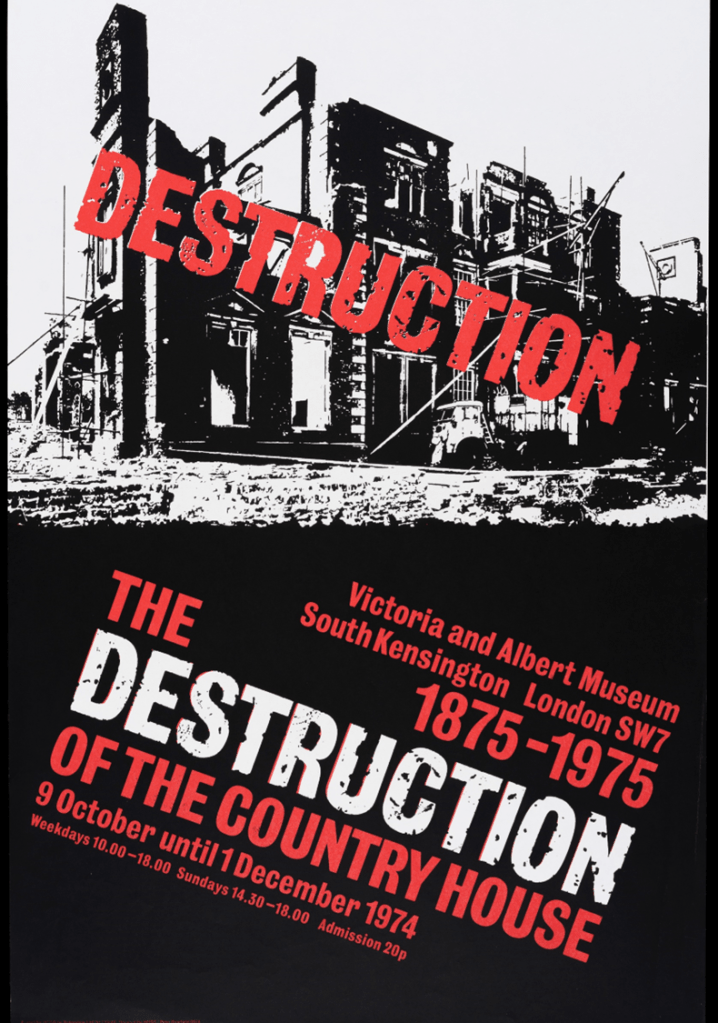

On 9 October 1974, on the day before the second general election of that year, the first visitors started making their way to the Victoria & Albert Museum to view the newly-opened exhibition: ‘The Destruction of the Country House: 1875 – 1975.’. Passing through the grand entrance to the monumental museum and then along the stately corridors would have heightened the shock as they entered a room to be faced with the toppling columns and seemingly endless photos of similar architecture which had been so ruthlessly demolished. However, as bad as the situation seemed – might the losses, though deeply regrettable, have been a catalyst for a better future for the country house?

Immersed in designer Robin Wade’s collapsing neo-classical portico, and as the late John Harris’ voice grimly intoned a roll call of the fallen, they may have wondered how such destruction could have been allowed.

To survey the country houses losses in the UK over the last century is to be staggered as to the diversity of beauty and history which has been destroyed. That’s not to say that everything that’s been built should or can be preserved, but the sustained pattern of losses of country houses was cumulatively one of the largest of a particular building type since the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Although each loss was individual, collectively, it was certain to be noticed and mourned. As the then head of the V&A, Roy Strong, considered the situation, it was clear that the time had come to raise awareness of the losses – but could it also help prevent further destruction?

For Strong, working with Marcus Binney and John Harris, the aim of the emotionally-charged exhibition was to:

…draw the public’s attention to the country house as a major part of our national heritage, showing the tragic losses over the last century, stressing the need to preserve important houses with their contents and setting intact, emphasising the positive achievements over the past twenty-five years, and forcibly pointing to the problems that lie in the future.

Strong also wrote that:

…the threatened Wealth and Inheritance Taxes if applied to historic house owners will see … the end of a thousand years of English history and culture, as pell-mell the contents are unloaded into the saleroom, the houses handed over to the Government or demolished. I can’t tell you the horrors looming unless one fights and intrigues at every level behind the scenes.

The V&A exhibition was a landmark in a number of ways. Rarely has an exhibition in a major national museum been so overtly polemical – and political. The Observer newspaper stated that it was ‘the most emotive, propagandist exhibition ever to grace a public museum’s walls’. The Daily Mirror took a rather more dismissive tone, rather snarkily observing that:

Gad…our stately homes are grim! Life in Britain’s stately homes is becoming simply too awful for the coronet set. Dukes, baronets and earls have to use buckets to catch rain dripping through the roofs. They shiver in front of electric fires because the central heating is faulty. (Roger Todd, Daily Mirror, 9 October 1974)

The stark reality of life in the country house had been at the forefront of Roy Strong’s mind when considering their presentation. In a letter from Strong, dated 24 June 1974, to Sir Osbert Lancaster, the social cartoonist and proposed contributor to the exhibition, he highlighted some of the threats to the country house in the twentieth century, including; taxes, loss of heirs in WWI, partial demolition or dereliction, sales of art, land…everything, motorways, urban expansion, conversion to some other purpose, even the National Trust, before culminating in…opening to the public.

Although the tone is ambiguous, flippant or haughty depending on your perspective, it is interesting that many of the eventual solutions to the problem of the demolition of country house are included. Conversion to alternative uses, be it offices, schools, or hotels, has saved hundreds of houses. The National Trust have been saviours of some of the crown jewels and helped to change the narrative around the purpose of the country house. This has included developing new ways to engage the public and future generations (and continuing to do so), solidifying the cultural foundation of the country house as part of our national recreational and cultural identity.

The November 1974 general election ushered in a new Labour government, during the midst of turbulent economic times. A government which would be considering how to implement their manifesto commitment of “…a fundamental and irreversible shift in the balance of power and wealth in favour of working people and their families.”. It was a bold move by the V&A to try to defend the mansions of the wealthy – but this was also a collective national heritage, even if privately owned. Counter-intuitively, by highlighting that another strand of the national fabric was not only fraying but had serious holes, it may have skilfully blended into general concerns about the overall fate of the nation.

The V&A was not acting alone. As Adrian Tinniswood highlights in ‘Noble Ambitions‘, 1974 was the year in which the country house owners got organised. John Cornforth’s report ‘Country Houses in Britain – can they survive?‘, published that year (by the then almost activist Country Life magazine), painted a dramatic picture of the almost perfect storm which he felt might have led to a crisis within 8-15 years, but was now looming large in the immediate future. Despite his pessimism, Cornforth later wrote ‘The Country Houses Of England 1948-1998‘ in which he strikes a much happier tone, saying:

‘The history of the English houses in the past twenty-five years has proved to be infinitely more positive, and the view of the future more optimistic, than seemed conceivable at the time of The Destruction of the Country House exhibition…when their very existence was threatened by new taxes.’

Back in 1974, Cornforth’s rather gloomy views were echoed elsewhere. In June, Lord Grafton (qualifications: Duke of Grafton, chairman of SPAB, member of Historic Buildings Council, the National Trust’s Historic Buildings Representative in the East of England, and owner of Euston Hall) spoke in the House of Lords to raise with his noble friends/fellow house owners, and the government, that the proposed wealth tax, and a transfer tax to replace death duties, spelled disaster for the country house. The influential Times newspaper editorial also weighed in, and the newly formed lobby group, the Historic Houses Association, emphasised the economic benefits, whilst also organising a petition which garnered a remarkable 1.25m signatures. This level of public support was in some ways unsurprising given that by 1972, 43 million visits were made to the 800 houses and ancient monuments open to the public.

Looking back now, the assumption seemed to be that owners of country houses had almost a right to perpetually live in them, and that the state should subsidise this. There is an argument that the state should look after the interests of all subjects, to a greater or lesser extent, but the preservation of the institution of the country house was certainly presented as one where protecting the elite benefited the nation, tapping into a deep cultural reserve of respect or deference – rightly or wrongly.

So, although the exhibition was one of the most high profile actions in defence of the country house, it was not without wider support and deep foundations. A preservationist ‘ley line’ can be drawn through the exhibition, connecting it to Historic Buildings and Ancient Monuments Act of 1953, which extended heritage protection to inhabited buildings, leading to a dramatic decline in the number of houses being lost. Although there were other earlier voices raised in defence of our built heritage, including Sir John Vanbrugh’s argument, in 1709, to preserve Woodstock Manor. Of particular note was Philip Kerr, the 11th Marquess of Lothian (1882–1940), who was the catalyst for the National Trust Act of 1937, which created the Country Houses Scheme which saved so many more houses from destruction. Also intersecting our ‘ley line’ is the establishment of the various amenity societies; the Victorian Society in 1958, the Georgian Group in 1937, the Ancient Monuments Society in 1924, and the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings in 1877.

It’s also worth noting that the dates referenced in the title of the exhibition extended into the future, if by only a year. The implication was that the destruction was still an on-going process to be feared, though this underestimated the almost immediate positive impact that it would have. The genesis of the exhibition was usefully covered in a blog article I wrote for the 40th anniversary which I would recommend if you’d like some further thoughts.

The exhibition exemplified the challenge of the definition of the reason for the country house; was it a home, a rural business, or museum? Or did, by the nature of the sometimes competing, sometimes intersecting interests of the owners, society, and the state, demand it be all these at once. Legislation crafted to protect or promote one aspect, may impinge on the ability for it to fulfil its other roles, creating a tension which actively threatened the long-term sustainability of the house.

Yet, one reason the exhibition was so successful, and had such a positive impact, was that it also gave hope. Despite the tone of Strong’s letter to Osbert Lancaster, displays showed how country houses could be adapted to survive with many a house escaping demolition through conversion to a school, offices, or hospitality. Sensitive sub-division into apartments by thoughtful developers such as Kit Martin, also offered long-term solutions. Indeed, a number of Kit Martin’s conversions, such as Gunton Park, Burley on the Hill, and Stoneleigh Abbey, are still prized today.

John Harris not only credits the demonstration of alternative uses, but also that there was grant support (though this has now been largely removed). As Giles Worsley noted in his magisterial book ‘England’s Lost Houses‘ (2002) that by the time the exhibition opened, the tide had already turned and the numbers of houses being lost had abated. The demolition of large houses such as Warter Priory (Yorkshire) in 1972, or the threatened total loss of The Grange, Hampshire, (even if it was gutted) was now more of an outlier than a regular occurrence.

Perhaps most importantly for country house conservation, the preservation of our wider architectural heritage, was the founding of SAVE Britain’s Heritage in 1975, by Marcus Binney, one of the co-curators of the exhibition. Binney has been an immense presence in campaigning across the country not only to fight for specific buildings but to change attitudes and the whole perception of the value of our nation’s architecture. Although he has been rightly recognised with an OBE and CBE, how he has not been given a knighthood for his work is one of those inscrutable mysteries. Sadly, the other curator, John Harris died in 2022 and will rightly be remembered as a brilliant architectural historian, with a sparkling wit and enormous fount of stories, particularly relating to his post-war exploration of these derelict mansions.

That the country house remains an easily accessible, and deeply symbolic, cultural touchpoint is a testament to strength of the concept, even though it is now rightly subject to a more honest examination of the history. A greater transparency only adds to the weight of interest in the houses and their extraordinary past, creating a flywheel effect to support further research. This doesn’t diminish the shorthand that the country house represents: beauty, tradition, continuity. To ensure that the concept of the country house remains viable, it has to be refreshed and reinterpreted. This synthesis of the realities of the present and the inheritance of the past, is what creates new opportunities for the country house, not only as an area of academic study, or as place of public culture and entertainment, but also, most critically, as a home.

Perhaps one of the most significant pieces of legislation in creating a sustainable future for the country house was not any of the heritage Acts. Until the Marriage Act 1994 the only ‘approved premises’ for a wedding ceremony was a church or registry office. After 1994, country houses were also considered appropriate venues, ushering in a new avenue for owners to secure an income from their asset. This brought about a fundamental change in the attitude towards the house, both from the owners, and now the wider public, who were now welcomed into these exclusive spaces. The emotional value invested in each occasion, has ensured that there is a ready army of those who will think fondly of a specific house, and often, the idea of the country house more generally.

So what is the future of the country house? To imagine that their current situation and the opportunities they have are guaranteed is fanciful. A recent Law Commission report suggested that weddings could be held in “any safe and dignified location” including family homes, forests, and village halls. Given the rising cost of hiring premium venues such as country houses, this risks driving them back into the more gilded edges of society. The sharply rising cost of maintenance and operating such a house, either as a venue or as a home, increases the risk of benign or malign neglect – the former from the family who don’t wish to leave, but struggle to afford to stay, or the latter; those who only see the opportunities to replace an existing house with something more modern, whilst enjoying the benefits of a location which has been carefully crafted by previous generations.

However, the concept of the country house remains surprisingly endurable. As an aspirational token of success, it has rarely been bettered. Ultimately, the ‘Destruction of the Country House’ exhibition continued the evolution of the country house, further democratising the concept and ultimately helping to build the political and social framework which underpins their survival and success. The fortunes which provides the funding are continually made and lost, with the country house and estate hopefully continuing to stand proud of such vicissitudes for future generations to enjoy.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted and very grateful to Dr Oliver Cox, Head of Academic Partnerships at the V&A South Kensington, who very kindly shared the materials from his lecture in May 2024 on the genesis and impact of the exhibition and gave his permission to use them. His research was facilitated by the excellent V&A Archives team and I echo his gratitude to them.

Further reading

If you are interested in finding out more, then my Amazon bookshop as well as a range of non-fiction and fiction books on country houses has a specifically-selected list of books on lost country houses.