As the costs of owning a country house mounted in the early-twentieth-century and eventually overwhelmed the finances of many families, so they sought alternative uses for their houses. Whether as a care home, school, or any of other myriad uses, few houses or their estates endured the experience unscathed. For those used as offices, the particular indignity of large, modern additions obliterated the immediate setting of a house, occasionally driving it into obscurity. Few who suffered this fate have ever escaped, yet a rare and beautiful survival – Benham Park in Berkshire – has not only escaped, but been wonderfully (partly) restored and is now offered for sale. What is most remarkable though about this house are its connections to some of the most famous names of Georgian architecture, including Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, a young Henry Holland, and an even younger John Soane.

Nestled in a lush parkland, Benham Park is significant as a formative experience, in different ways, for both Holland and Soane; a house where the two would each contribute in different ways, each gaining experience which would serve them well in the future. The noted architectural historian Dorothy Stroud declared Holland ‘a designer of perception and originality’. Her tireless research underpins much of what is known about Holland and his work.

Henry Holland (b.1745 – d.1806) was one of the leading architects during the reign of George III. Today, his reputation has been overshadowed by his contemporaries who were more willing to engage in courting public notice, such as by exhibiting their work at the Royal Academy, which Holland never did. Chiding a friend in 1789, he stated ‘Pray no more public compliments to me. I began the world a very independent man and wish to hold it at arms length…I find myself already more the object of public notice than suits my disposition or plan of life’.

Henry Holland was the son of Henry Holland (1712-1785 – to avoid confusion, the father will be referred to as ‘the elder Holland’, any other mentions of Holland are the son) of Fulham. A successful master builder, he built many important houses in the middle years of the eighteenth-century and worked with architects such as Robert Adam, executing his alterations to Bowood in Wiltshire in 1761 and, in the same year, working at Ashridge House, Hertfordshire. It was this latter commission which was to prove singularly important as it established a professional relationship between Holland senior and Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown (b.1716 – d.1783), a landscape architect still revered today for his skill and imaginativeness. Brown’s particular ability was to be able to envision a whole landscape as it would be after the planting had reached maturity – to see its ‘capabilities’.

He was also noted architect, with even his rival Humphrey Repton praising the ‘comfort, convenience, taste, and propriety of design in the several mansions and other buildings which he planned’. The houses include Croome Court, Worcestershire (though the design may have been provided by Sanderson Miller), Corsham Court in Wiltshire (1761-64), Broadlands in Hampshire (1766-68), Fisherwick Park in Staffordshire (1766-74 – dem. 1814-16), Redgrave Hall in Suffolk (c.1770 – dem. 1946), Claremont House in Surrey (1771-74), and Cadland in Hampshire (1775-78 – later much enlarged – dem. c.1955).

Although the initial connection was with the elder Holland, Brown would become central to both the professional and personal life of the younger Holland. Although he never undertook a Grand Tour, his education was more practical, working with his father in the family business. Holland displayed aptitude and skill, taking on more responsibility but also his talent for design was becoming clear. With his father’s connections, Holland was taken on as architectural assistant in 1771 by ‘Capability’ Brown who would, in time, hand over much of his design work to Holland, who would use these earlier designs as inspiration. The closeness and respect between the two can be gauged by the marriage of Henry Holland to Brown’s daughter, Bridget, in 1773. Professionally, a measure of the level of joint enterprise between Colvin notes that Claremont and subsequent houses are jointly attributed to Holland.

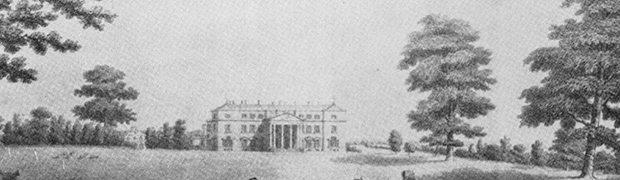

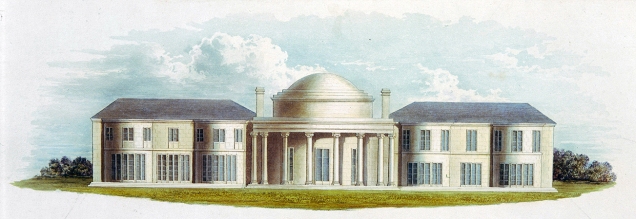

Benham Park was an easy commission of Brown to secure, though it was likely that he was primarily thinking of his new partner when doing so. The probability that Brown would be commissioned was high as he was already working for the owner of the estate, William Craven, 6th Baron Craven (b. 1738 – d.1791), on another country house for him, Coombe Abbey, Warwickshire. Apparently under pressure from his wife, Elizabeth Berkeley, Lord Craven wrote to Brown saying ‘Lady Craven wishes to make some alterations here and to begin immediately’. Holland and Brown submitted their designs for a house in September 1773 using a similar pattern to Brown’s previous work with a neoclassical, two-storey main house with grand central portico.

The house was built between 1774-75, the final result a sympathetic marriage between an elegant yet imposing house and the Arcadian pleasures of a sculpted landscape. Despite these fine attributes, Benham has been rather overlooked in the histories of both Brown and Holland with the latter clearly learning important lessons from one who designed with practicality in mind, but not to the exclusion of an element of drama. However, Holland was not without his own influence as Stroud notes that from the time he joined Brown’s office, the interior design evolved from a more robust Palladian character to the more restrained yet elegant style which was Holland’s hallmark. Claremont, Cadland, and Benham all display this style, indicating that although the shell of the house was more the work of Brown, the interiors were to Holland’s designs.

What’s remarkable about Holland was his almost precocious drive to build on a grand scale. Backed by his father’s capital and expertise, Holland leased in 1771, aged 26, eighty-nine acres of what is now Chelsea and Knightsbridge, including what is now Cadogan Place, and proceeded to speculatively design and build houses based around a miniature park or garden square. This high profile activity brought Holland his first major solo design for Brook’s club in Mayfair, London, a haunt of the Prince Regent and Whig aristocracy. This would lead to the Prince commissioning two major buildings from Holland; Carlton House and Brighton Pavilion. These two commissions plus Holland’s speculative building cemented his position within the highest social strata, creating future opportunities.

Other significant commissions included the the refurbishment in 1787 of Althrop, Northamptonshire, for the 2nd Earl Spencer, including a full re-casing of the red-brick house in white mathematical tiles with stone dressings, a re-design of the gardens, and inside, a re-ordering of the accommodation including the creation of the noble triple libary, divided into sections by screens of Ionic columns. Another Whig patron was Francis, 5th Duke of Bedford, who had Holland complete some minor works to Bedford House before commissioning more extensive work, also in 1787, at his main house at Woburn Abbey. Holland was back at Broadlands in 1788 creating a new vestibule and inner hallway, the entrance marked by a new grand portico. In 1795, after a sojourn into theatres, Holland returned to grand country houses, with the rebuilding of Southill Park in Bedfordshire for Samuel Whitbread, of brewing fame. Again, as with Althorp, this was a refurbishment to the point of rebuild; the house encased, the accommodation extended and a new portico added. His last commission was again from Lord Spencer in 1801 to rebuilt his Wimbledon house, which had earlier burnt down, with a sophisticated villa in a severely plain style both inside and out. Sadly, this was demolished in 1949.

Benham Park was also important for another young, aspiring architect, Sir John Soane. As a young apprentice, Soane had joined Holland’s office in 1772 as a junior. At Benham, Soane was given the task of measuring up to create the final bills, a task he was to repeat at other locations, giving him a valuable insight into not only the process of building but also the business aspects. Although, sadly, almost all Holland’s papers and drawings were posthumously destroyed by his nephew, one of Holland’s account books is preserved in the Soane collection. Soane seems to have retained it as a valuable record and tool when setting up his independent practice. Benham therefore provided practical, aesthetic and business training to the young architect who no doubt admired Holland’s neo-classical approach before evolving his own distinctive response and style, which was to establish him as one of the leading architects of his age.

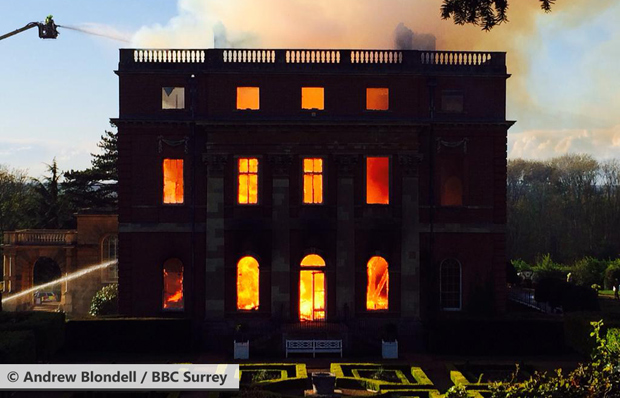

Benham survived largely unaltered into the twentieth-century until 1914 when the pediment was removed from the portico and replaced by a balustrade. This was echoed at the roof level where the pitch was lowered and obscured by a pierced stone balustrade. The servants quarters were removed at the same time due to their poor condition. The house and estate remained with the Sutton baronets until 1982 when it as bought and converted into offices in 1983, with additional office blocks built next to the house. These were thankfully demolished as part of the latest restoration of the house and estate.

Benham Park, (Grade II*), is now offered for sale with 130 glorious acres for £26m. Inevitably for a house of such grandeur situated so close to London, there are approved plans for the house to become a ‘wellness’ centre with a huge (though thoughtfully designed) extension to the side and rear. For me, as ever, this is a house which would be best served by being returned to it’s original purpose, that of a family home. For a new owner, they could revel in the knowledge that the house and landscape had been conceived by one of the great Georgian partnerships of Brown and Holland. Standing under the portico today, much as where they and the young John Soane must have once stood, the latter on the cusp of his era-defining career, looking out at Brown’s landscape, they can appreciate this rare combination of architectural genius – truly a prize worth such a princely sum.

Estate agent particulars: ‘Benham Park, Berkshire‘ [Savills]

Brochure (PDF): ‘Benham Park, Berkshire‘ [Savills]

Listing description: ‘Benham Park‘ [Historic England]

Please note: Savills very kindly provided the images and brochure but had no input into the text.