Many country houses we can visit today are innately interesting; the design, the contents, the occupants, all tell a tale. Sometimes though there are houses with a much richer past which not only have an immediate story to tell but also a much more complex history, one fascinating for anyone with an interest in how these houses came to be created. One such house which was recently launched – and amusingly described on Rightmove as a ‘60 bedroom detached house for sale‘ – is the remarkable Bylaugh Hall in Norfolk, an engineering marvel and architectural delight, which had a forced birth through litigation, which wasn’t wanted by the first owner, and where credit for the design hasn’t truly been given to the right architect.

Bylaugh is remarkable in many ways; some obvious, others less so. Even its genesis came from beyond the grave as the controversial inherited wish of the last owner, Sir John Lombe Bt (b. c1731 – d.1817), a man whose fortune came from the family’s silk throwing mill in Derbyshire. The Lombe’s were established Norfolk gentry whose original estate was at Great Melton, centred around Melton Hall (built in 1611 by the Anguish family) but now a ruin having been first tenanted and then, by the end of the 19th-century, abandoned.

Allegedly won by Sir John in a skewed card game, the Lloyds had owned the Bylaugh estate for a number of years, and even if the story is false, it was legitimately Sir John’s by c1796. The Lombe’s were unusual in that their wealth largely came from industry, and one which was located outside of the county, but they quickly used their fortune to create the fourth largest estate in Norfolk, at over 13,000-acres by 1883.

Whatever house was already at Bylaugh was insufficient for Sir John so he resolved to build an entirely new one. However, the house he had in mind was not the house which was built. Sir John must have had a fair idea that he would not survive to see his grand plan to fruition but he certainly wasn’t going to let mere death cheat him of his ambition. Having placed £20,000 in trust for the express purpose of building the house – though without approving a design – he died in 1817 (unmarried and childless), leaving his estate and his firm directions to his brother Edward. Here, the family history becomes a little complicated as Edward was his half brother, the product of an affair with a Norwich doctor’s wife. Edward adopted the Lombe surname but was reluctant to take on the grand role envisioned by his late brother – which is perhaps why Sir John’s will was so prescriptive, and which led to a quite extraordinary court case.

Edward Lombe disputed with the executors of the estate the instruction to build the new house. However, Sir John had been quite clear, including this fascinating clause in his will:

And whereas it is my wish and intention that a mansion house and suitable offices fit for the residence of the owner of my estate shall be erected on some convenient spot in the parish of Bylaugh in the county of Norfolk either in my lifetime or after my death and that if I shall not erect the same in my lifetime then that my said trustees shall forthwith after my death erect the same according to such plan as I shall in my lifetime approve of or if I shall die before such plan shall be prepared and completed then according to such plan as the trustees or trustee for the time being under this my will with the consent of the person for the time being beneficially entitled to the immediate freehold of my said manors &c under this my will shall think proper to adopt adhering as closely as possible situation and other incidental circumstances being considered to the plan of the house now the residence of Robert Marsham esquire at Stratton Strawless in the said county of Norfolk. (source)

Yet Edward resisted, delaying the start of the build for years by arguing with the executors, Mr Mitchell and Mr Stoughton, and stating that even if they built the house he wouldn’t live in it. Finally, in 1828, he went to the Court of Chancery and demanded that the money, now having grown to £43,000, be placed with it and a judgement made as to whether he could overturn the provisions of his brother’s will. The case was still undecided in 1839, by which time the fund had grown to over £63,500, when Edward again pressed his case, with a decision finally being made in 1841 – against him. The Vice-Chancellor said:

It appears to me to be impossible to read this passage in the will without seeing that there is in the plainest language an express trust for the erection of the mansion house which the trustees are forthwith after his death to commence and to proceed with the erecting of. I cannot conceive any words more plain.

Which rather settled that. In the meantime, the executors had not been idle in their duties – but they weren’t as obedient as they might strictly have been. Sir John had clearly stated that the house was to follow ‘as closely as possible‘ Sir Robert Masham’s house at Stratton Strawless; a three-storey (now two), strictly classical, almost Palladian house with a Tuscan-columned porch. However, the executors ignored this provision and with possibly an eye to emphasising the esteemed family line and to help the new house blend in with the other seats in the area, they chose to create a historical ‘Jacobethan’-style house – but even that is not the one we see today.

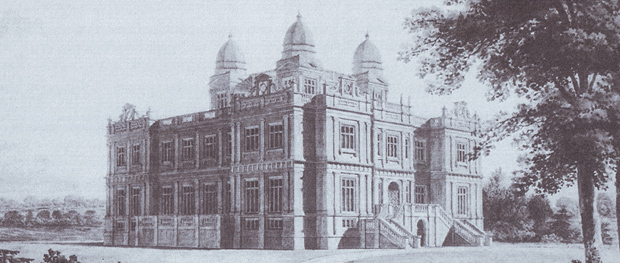

Interestingly, although the current Bylaugh is rightly described as being designed by Charles Barry the younger and his partner, Robert Robinson Banks, few are aware that in 1822 the trustees had originally asked another noted architect, William Wilkins (b.1778 – d.1839), to draw up a plan, and his design showed a remarkable stylistic similarity to the one actually built 27 years later.

Although a noted proponent of the Greek Revival, Wilkins, like many an architect, was well-educated in other styles and could turn his hand if asked. Clearly inspired by the style of ‘Prodigy‘ houses such as Burghley and Longleat, he also drew on elements of buildings he had seen and studied – for example, the polygonal domes capping the raised central hall are copied from the Porta Honoris at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, on which Wilkins had written a scholarly article for the esteemed ‘Vetusta Monumenta‘ in 1809. Although each façade was similar, the entrance front was enlivened by a projecting centre bay above the door which was on the piano nobile, reached by an elegant split stair.

The plan of the house was also modern, rejecting a rambling layout, and firmly following the Palladian 3×3 grid on the ground floor. Centred around a double-return staircase, this was an innovative layout for an early Victorian design – though one Wilkins the classicist would have been entirely comfortable with. Essentially, he had designed a Palladian villa, dressed in the architectural garb of the ‘Jacobethan’ style.

Bylaugh Hall, as attributed to Barry and Banks in 1849, was perhaps better described as an updated version of Wilkins earlier plan – the core 3×3 layout remained, as did the external style, though some of the details such as the raised central hall and domes were removed, and the central staircase replaced by a saloon. The construction did display some innovation, being one of the earliest steel-framed buildings and was considered a success with one rather giddy local newspaper exclaiming ‘Neither Holkham nor Houghton, those Norfolk wonders, can compare with it for either appearance or comfort‘. Such wild exaggeration aside, this was a house at the forefront of domestic convenience and was commended in The Builder for having no corridors in the main block, which maximised the space. It was completed in 1852 at a cost of £29,389, and by 1869 it was reported that £38,000 had been spent on the project, which would have included further works on estate buildings and landscaping (see photos of the house and grounds c1917). An interesting aside is that during the delay in starting the money had grown to quite a considerable sum, more than enough for all the works. Edward Lombe applied for the remainder but the Court demanded it be spent on bricks and mortar and so a 4-mile perimeter wall was constructed to satisfy this.

It seems that no descendent ever loved the house. By 1878, the then owner, Edward Henry Evans-Lombe, was renting the handsomely Classical Thickthorn Hall, before buying Marlingford Hall, whilst selling off outlying parts of the estate. In 1917, Bylaugh Hall and the 8,150-acre estate were put up for auction in 140 lots but Edward sold it whole for £120,000, and the hall and 736-acre park were subsequently sold to the Marsh family. Used by the RAF in WWII, it was sold in 1948 to a new owner who unsuccessfully planned to turn it into a nursing home. At that nadir of country houses generally, a familiar pattern started; parts of the house were demolished and in June 1950 a 350-lot demolition sale was held which stripped the interiors of the house, creating a gaunt and sad shell. So it remained until, in 1999, the house and a lodge was sold to a local sculptor who dreamt of fully restoring the house but with insufficient funds he was forced to restore just the Orangery (article by the engineers with lots of photos), intending it to be a wedding venue. Other parts of the main house were parcelled up as investments and rebuilt but the plan faltered and then failed, leaving the partially restored house we see today.

So Bylaugh Hall is a house paid for by a man who never got to see it, with a design chosen by two men who ignored the last wishes of the patron, with credit for that design going to two men who relied heavily on another architect now obscured, for a beneficiary who really didn’t want it in the first place. A brilliant story richly illustrating the fascinating complexities of our country houses.

So what should happen to this superb house? Interestingly, the 557-acre Pavilion farm which surrounds the east and south of the house, and includes one of the original lodges, is also for sale, providing the opportunity for the right person to combine them both. It would require real vision – the restoration work at Bylaugh Hall may be sound but the aesthetics are dire. Given the budget, much of the existing restoration should be stripped right back and the interiors given the lavish attention they demand. This is a house which cries out for sumptuous plasterwork and panelling, for grand rooms with fine wallpaper and filled with artworks and quality furniture. With the funds and the vision to take advantage of this rare opportunity, a restored Bylaugh Hall, combined with the farm and more land later, could once again create one of the finest estates in Norfolk.

—————————————————————————–

Property details

- Bylaugh Hall, £1.5m, 18-acres [Chesterton Humberts]

- Pavilion Farm – oieo £5.25m, 557-acres [Strutt & Parker]

- ‘A 60 bedroom detached house for sale‘ [Rightmove]

1917 auction catalogue:

- ‘Bylaugh Park Estate of over 8,150 Acres‘ [Bawdeswell.net]

- Photos of Bylaugh Hall and gardens [Bawdeswell.net]

Listing description: ‘Bylaugh Hall‘ [British Listed Buildings]