Country houses have been slightly glibly described as ‘prisons’, usually due to the restrictive social conventions, which stifled the freedom of the occupants. However, country houses have occasionally been repurposed as true custodial institutions, serving as prisons, youth detention centres, approved schools, prisoner-of-war (POW) camps from the 18th century to the present. This role is one which has been often overlooked in the history of the country house.

A fictional prison

If one wished, it was always possible to cast the country house as a prison, of sorts. The restrictions placed on everyone who lived in one, whether as the lord or the lowliest servant, was a web of both explicit and implicit rules. Although they could, in theory, walk out of any unlocked door, the reality was that they were trapped, bound to the building.

Fiction has long played on this idea, weaving physical incarceration, with its psychological equivalent. There are the self-imposed emotional bonds which confine the jilted Miss Havisham to her decaying Satis House in Charles Dickens’ ‘Great Expectations‘ (1861), or the fear which entraps the governess at Bly House in ‘The Turn of the Screw‘ (1898) by Henry James. In ‘Rebecca‘ by Daphne du Maurier (1938), Manderley, the grand estate in Cornwall, becomes a place of psychological imprisonment for the unnamed narrator. Haunted by the lingering presence of her husband’s first wife, Rebecca, the narrator feels trapped by the oppressive atmosphere of the house and the expectations imposed upon her. More recently, in Sarah Waters’ ‘The Little Stranger‘, the decaying Georgian mansion of Hundreds Hall (played by Newby Hall, Yorkshire in the film), becomes a symbol of entrapment for its inhabitants as their financial decline echoes that of their place in society, leaving them isolated.

Beyond these intangible confines, the house as a cell was perhaps most famously portrayed with Bertha Mason, Mr Rochester’s wife, confined as the ‘mad woman in the attic’ of Thornfield Hall in Charlotte Brontë’s ‘Jane Eyre‘ (1847).

Royal confinement

Beyond fiction, the country house has, at times of need, served in reality as a place of confinement – pressed into service as a working prison when circumstance demanded.

On 16 May 1568, Mary Queen of Scots fled to England seeking refuge from political turmoil in Scotland after the battle of Langside and spent her first night at Workington Hall, Cumbria. Mary had come to England in the hope of gaining support from the Catholic nobility and of appealing to her cousin, Queen Elizabeth I, for political assistance in regaining her Scottish throne. However, because both women were descended from Henry VII, Mary possessed a strong claim to the English crown. This made her presence in England a direct threat to Elizabeth, particularly as Mary was a Catholic alternative to Elizabeth’s Protestant rule.

Although Mary was technically a guest, she was heavily guarded and this effectively marked the beginning of her nearly 19-year imprisonment before her execution. Mary was moved around regularly to thwart plots to free her, from castles to eventually the country houses of George Talbot, the 6th Earl of Shrewsbury (b.1522 – d.1590). The Earl of Shrewsbury, famously married to Bess of Hardwick, played a pivotal role in the confinement of Mary, having been appointed her custodian by the Queen. Throughout various periods, he held Mary at his family’s houses including Wingfield Manor, Hardwick Hall, Chatsworth House, and Sheffield Manor – all situated within a 15-mile radius in Derbyshire. Mary was finally moved to Fotheringhay Castle, Northamptonshire, arriving on 25 September 1586. She was put on trial in October, and then executed in the Great Hall on 8 February 1587. Her long confinement within such grand yet guarded houses stands as a stark reminder of how the architecture of luxury could so easily become the architecture of captivity.

A prisoner of war

In wartime, country houses have been pressed into service in a wide variety of roles, with prisoner-of-war camps among the least glamorous. Stepping beyond the more obviously martial associations of castles, one of the earliest – and most notorious – examples was at Sissinghurst in Kent during the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763). The house, by this time had been allowed to fall in to a significant state of disrepair by the then owners, the Baker family. The government rented the property and adapted it to hold around 3,000 French naval prisoners, during which time it was further mistreated with the inmates destroying panelling, fireplaces, the chapel furniture, and leaving the garden a wasteland.

In 2008, a newly identified watercolour emerged that provides the most complete known view of the Elizabethan house during this period when it was a prison – and includes the chilling depiction of a double murder.

On 9 July 1761, whilst guarded by local, poorly-trained, armed militia, three prisoners who had escaped were being brought back to the camp. Their arrival caused a group of prisoners to rush to the fence out of curiosity. One of the militia, a hot-head called John Bramston, shouted that they were to come no closer or he would fire. He loaded his musket with three balls and fired at the group. One ball struck the wall, the other two each hitting a prisoner. One by the name of Baslier Baillie was wounded (shown top-left being helped by two friends), but another, Sebastien Billet, was killed instantly. Bramston was unrepentant. The picture is thought to have been painted by a Frenchman to record the crime – but in doing so also left a powerful visual record of a now much-altered house and its time as a prison.

World War II

During the twentieth century, several distinguished country houses were temporarily repurposed to serve the needs of war, their refined architecture providing an incongruous backdrop to confinement. At Huntercombe Hall in Oxfordshire, the late-Victorian mansion, with its commanding stone façade and landscaped setting, was requisitioned during the Second World War as a secure detention site, most notably for high-ranking German prisoners including Rudolf Hess, whose isolation lent the house an unlikely role in wartime diplomacy and intelligence. In north London, Trent Park, a neo-Palladian villa by Sir William Chambers, was adapted as a special interrogation centre, where senior German officers were held in conditions of deceptive comfort while their conversations were secretly recorded – its grand rooms thus becoming instruments of psychological warfare.

Similarly, Mytchett Place, Surrey, during 1941–42, this Victorian mansion was fortified and codenamed “Camp Z,” serving as a one-man prison wired for surveillance for the detention of Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess.

Further north, the Huntroyde Hall estate in Lancashire, long the seat of the Starkie family, was similarly turned over to military purposes, its once-private parkland accommodating prisoners and personnel within hastily erected compounds. As with Sissinghurst, the mistreatment during the harsh use as a prison was a significant factor in its later demolition. Earlier, in the First World War, the partly medieval Badsey Manor House in Worcestershire was similarly employed to house prisoners of war, marking a utilitarian phase in its long domestic history.

The changing attitude to the role of prisons

The use of country estates and their houses was partly one of necessity in wartime, but in the post-war period also reflected a change in attitudes towards a more therapeutic approach towards incarceration from the 19th-century focus on harsh conditions and hard labour as a deterrent.

Why country houses? They offered several advantages: privacy (away from cities, escapes less dangerous to public), space for agriculture and workshops (important for training prisoners in trades), and an existing infrastructure of accommodations and kitchens. Also, symbolically, placing prisoners in a “less oppressive” environment was meant to encourage self-respect and responsibility – a deliberate contrast to the austere walled prison. Askham Grange’s homely appearance was cited as beneficial for women.

The open-prison concept drew heavily on Alexander Paterson, who joined the Prison Commission in 1922. He argued that imprisonment should actively shape behaviour for the better, with inmates encouraged to develop through structured physical and mental activity.

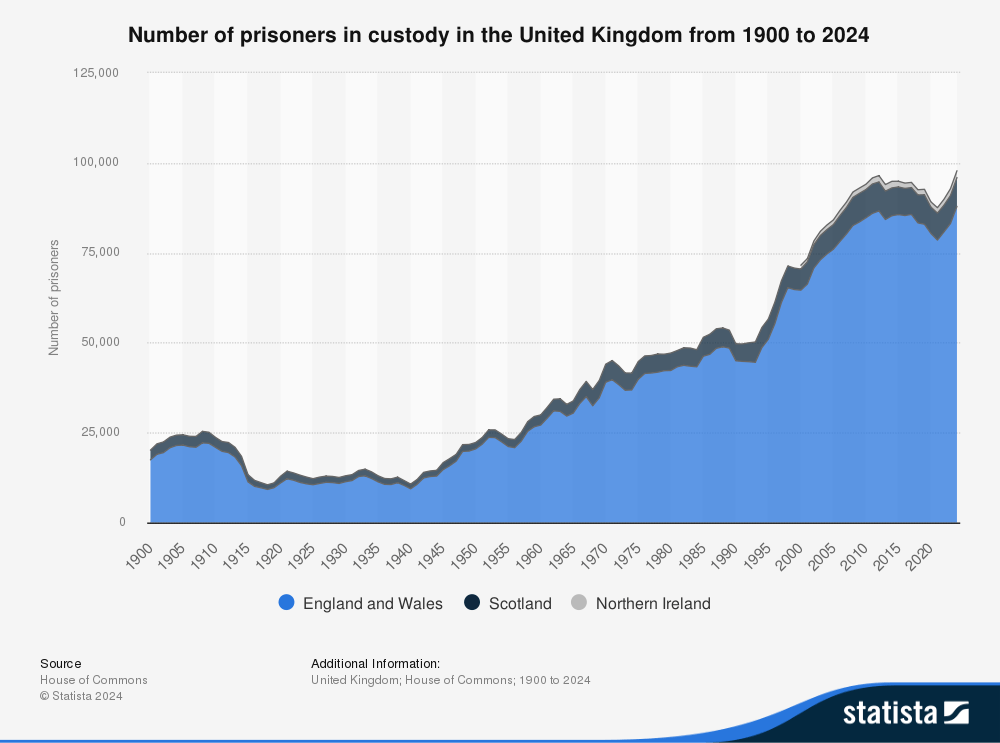

In the 1940s, there had been a steady increase in the total number of people convicted of indictable offences. During a House of Lords debate on Penal Reform in November 1946, the Lord Chancellor, Lord Jowitt, lamented the tendency towards increasing crime before WWII, stating that,

I take the five years 1934–1938. The number of young persons found guilty of indictable offences moved up from 10,000 odd in 1934 to 14,000 odd in 1938 – that is males; females from 1,300 odd in 1934 to 1,600 odd in 1938. …When we have the figures of 14,000 young men and 1,600 young women going up to the sort of figures we have to-day [1947], for the total number of persons – 78,000 in 1938, moving up in 1945 to 116,000…it is quite obvious that we have here a very real problem. (Source: Hansard – column 442)

The noble Lord’s figures indicated a serious issue so whilst not everyone convicted was incarcerated, there was a steady rise in the prison population:

The sustained increase in the total population by over 50% from 1940-1950, would place significant stress on any system of incarceration. However, attitudes had changed and the harsh conditions of punishment of the nineteenth century were now considered to do more harm than good, especially for young offenders. The Criminal Justice Act of 1948 introduced major reforms for young and habitual offenders. It barred sending under-21s to prison except as a last resort, directing them instead to borstal training or, for shorter terms, to detention centres.

This more enlightened perspective, which the Lord Chancellor was fully supportive in that same debate, created a requirement for a system which emphasised a more probationary approach via the borstal system. By relying on less stringent security, and often promoting training and useful labour – particularly agricultural – this created a means to reform and improve the lives of those who had been convicted. The Lord Chancellor welcomed that:

Thank goodness, we are now approaching the time when it will no longer be necessary to detain in prison for long periods persons who are ultimately going to serve their sentences in Borstal. The institutions we now have are of very varied types. Sometimes they are in a camp and sometimes they are in a country house, where the inmates can be engaged on agricultural work. We have also opened a new Borstal institution for girls at East Sutton Park in Surrey. That is a small institution and will take some fifty girls. (Source: Hansard – column 447)

Interest also developed in adapting elements of the short-lived but influential “Wakefield experiment,” introduced during the First World War to manage the most uncompromising conscientious objectors – the Absolutists – who refused all military orders. Previously held in ordinary prisons, they became the focus of MPs arguing for more humane treatment. The government resisted releasing them but agreed to trial a compromise by placing all COs under a new regime at Wakefield.

This system relied on a high degree of trust. Cell doors were left unlocked, prisoners could move freely within the prison, and a small allowance allowed them to buy writing materials and tobacco. Conditions were not freedom, but a clear improvement. Leisure and work were timetabled, with expectations of diligence and no “singing, shouting, whistling, or reading” during working hours. The experiment collapsed when the men rejected the rules they had helped draft, leading to their return to standard prisons. Even so, its central idea – combining restrictions with opportunities for responsibility and reform – would influence later thinking about penal regimes.

Speaking during the same debate in 1946, the Lord Chancellor again highlighted that such facilities were being developed:

We have recently taken over a former hospital at Tortworth [Court] in Gloucestershire as what is called a minimum security prison for selected convicts. In that way we can do much towards their rehabilitation and their ultimate reassimilation into ordinary civilian life. (Source: Hansard – column 447)

This approach influenced the selection of suitable locations for the new prisons. At HMP Leyhill, the government repurposed an ex-American Army hospital camp on the Tortworth estate to create the first open prison in 1946. The adjacency of Tortworth Court (then still with the Earl of Ducie) gave the model of a country setting if not using the main house. Interestingly – the house was not taken as it was returned to the Earl; but by the 1950s, Leyhill expanded and did start using some estate buildings, thought the wider estate is still owned and managed by the Earl of Ducie’s family as Tortworth Estates.

Hewell Grange

Hewell Grange epitomizes the pattern for long-term penal conversion. An existing country house could be successfully integrated into the penal system for decades, effectively becoming a self-contained village (with a chapel, workshops, and housing all on site).

The grand main house, last great prodigy houses of its era, provided an environment, even when not used directly as cells for prisoners, was arguably more humane than a typical prison – former inmates often remarked on the beauty of the lake and gardens, which were part of a 250-acre landscape park laid out by Capability Brown, with formal terraces, a lake, and extensive service buildings. By the lake are also the ruins of Old Hewell Grange, the classical predecessor to the current house. After being superseded by the new Hewell Grange in the 1890s, it was accidentally gutted by fire and abandoned, and now survives as a roofless ruin, its classical form still partly visible among collapsed walls and encroaching vegetation.

The new house was built between 1884 and 1891 for Robert Windsor-Clive, later 1st Earl of Plymouth, Hewell Grange cost approximately £250,000 (equivalent to spending c.£39m today). Designed by George Frederick Bodley and Thomas Garner in the Jacobethan style, the red brick house with stone dressings features an E-plan, steeply pitched gables, clustered chimneys, and mullioned-transomed windows. Interiors include carved oak panelling, a double-height Great Hall with a minstrel gallery, and elaborately modelled plaster ceilings.

However, Hewell Grange also reveals both the potential and limitations of prison use: spacious and already built, the house saved the state construction costs in 1946; but by 2019, it was anachronistic and expensive to run. By the 2010s, the UK prison estate was being rationalized. In 2019 the Ministry of Justice announced the closure of the open prison at Hewell Grange, following a critical inspection report and also reflected the cost of maintaining an ageing mansion for modern custody standards. The prison formally closed in 2020, and the entire site was consolidated into one (closed) prison to the north east of the house, around 600 meters away.

Hewell Grange house is now vacant and lacking a clear future, beyond occasional use for filming and events. As is so often the case for heritage without a viable and sustainable purpose, its condition has deteriorated to ‘poor’ after closure, with concerns about lack of maintenance, resulting in it being placed on the Heritage at Risk Register. As of early 2022, the government put the property up for sale, seeking a new custodian to repurpose the historic estate once again.

It was apparently sold in 2023 to a hotel group but it’s unclear whether this fell through or they immediately put it back on the market, as it has been offered through Cushman & Wakefield, with 247 acres, for an undisclosed price. This inevitably raises questions about the future: will it return to a private residence, become a hotel or institution, or will it just be allowed to deteriorate until it becomes another country house to succumb to neglect, urban exploration or a mysterious fire?

Conclusion

The pattern of country house reuse reflects adaptability to historical moment. In wartime, necessity drove usage; in peacetime, policy experimentation and economic forces did. This practice peaked in the mid-20th century and today it would exceptionally unlikely for a house to be taken over for this purpose, with a clear preference for building dedicated facilities.

From a wider heritage perspective, Hewell Grange’s story is instructive as, unlike so many country houses that were demolished in the mid-20th century, the use as a prison provided a value and so it was preserved precisely because it found an institutional function. Now its preservation will depend on finding a sympathetic new use after its institutional life has ended.

A list of country houses used (either currently or previously) for incarceration by the state since 1900

| Prison name | Country house | County |

| Askham Grange | Askham Grange | Yorkshire |

| Blundeston | Blundeston Lodge | Suffolk |

| Buckley Hall | Buckley Hall | Lancashire |

| Bullwood Hall | Bullwood House | Essex |

| East Sutton Park | East Sutton Park | Kent |

| Erlestoke | Erlestoke Park | Wiltshire |

| Foston Hall | Foston Hall | Derbyshire |

| Hewell | Hewell Grange | Worcestershire |

| Hill Hall | Hill Hall | Essex |

| Humber | Eventhorpe Hall | Yorkshire |

| Kirklevington Grange | Kirklevington Grange | Yorkshire |

| Latchmere House | Latchmere House | Surrey |

| Littlehey | Gaynes Hall | Cambridgeshire |

| Lowdham Grange | Lowdham Grange | Nottinghamshire |

| Morton Hall | Morton Hall | Lincolnshire |

| Penninghame House | Penninghame House | Dumfriesshire |

| Spring Hill | Grendon Hall | Buckinghamshire |

| Stocken | Stocken Hall | Rutland |

If I have missed any others, please share the details in the comments or contact me directly and I’ll update the list.

Sites associated with nearby country houses

| Prison name | Country house | County |

| Eastwood Park | Eastwood Park | Gloucestershire |

| Leyhill | Tortworth Court | Gloucestershire |

| Swinfen Hall | Swinfen Hall | Staffordshire |

Selected references

- ‘Juvenile delinquency and the evolution of the British juvenile courts, c.1900-1950‘ (Kate Bradley, University of Kent)

- Thomas, Roger J. C. Prisoner of War Camps (1939–1948): Project Report. English Heritage, 2003.

- Robinson, John Martin. Requisitioned: The British Country House in the Second World War. Aurum Press, 2014.

Further research

Interestingly, the subject of the use of the country house for incarceration doesn’t appear to have been covered in depth academically, as far as I could discover. Given the numerous angles, this would appear to be an area which someone may wish to investigate further as the official records and related information would probably reveal a richer story than I have been able to share here. Happy to have a chat if anyone wishes to take it on.