One of the joys of Country House Rescue is to bring to light some of the lesser known houses. The subject of this week’s edition (12 July, 20:00, Channel 4), Meldon Park in Northumberland, can certainly be said to be one of the ‘illustrious obscure‘. This is also perhaps an apt description of the architect, who was one of the most prolific in the north east of England yet surprisingly little known beyond that, though the house also features later work by another who was certainly famous. Yet, such noble associations do not pay the bills so, despite a 3,800-acre estate, the Cookson family have called in the services of Simon Davis to provide ideas to help keep the house in the family.

Meldon Park is certainly an elegant essay in the neo-Classical; golden brown sandstone in a compact and elegant design with some superb subtle detailing which denotes the hand of a finer architect. The entrance front, though only three bays wide, features a grand porch with four free-standing (or ‘tetrastyle prostyle’ if you’d prefer the architectural terms) Ionic columns, projecting from a slight recession of the middle bay, with the corners of the building marked by shallow pilasters.

The architect of the now grade-II* Meldon Park was the regionally prolific John Dobson (b.1787 – d.1865) – a name famous in the north east but, due to his geographic focus, one less known nationally. Dobson was born in Chirton, County Durham, and showed an early talent for drawing which led, at the age of 15, to his becoming a pupil of leading Newcastle architect David Stephenson. On completing his studies in 1809, Dobson moved to London to develop his skills further, studying under the famous watercolourist John Varley. In London, Dobson became friends with the artist Robert Smirke and his two architect sons Robert (who designed the main facade of the British Museum) and Sydney (who later married Dobson’s daughter). Despite the urging of his friends to stay in London, Dobson moved back to Newcastle where he established his practice, becoming (reputedly) the only architect between York and Edinburgh, except for Ignatius Bonomi in Durham.

Dobson proved to be an exceptionally capable architect; not only could he produce beautiful and convincing watercolours of proposed projects, he was also technically competent, to the extent that his daughter claimed he ‘…never exceeded an estimate, and never had a dispute with a contractor‘. Dobson is perhaps best remembered for designing much of central Newcastle, and in particular, the beautiful curved train shed at the Central station. Despite his urban output, Dobson was also extensively involved in projects outside of the towns, designing or altering over sixty churches and more than a hundred country houses; the latter principally commissioned by the beneficiaries of the wealth of the Industrial Revolution. Dobson was a rare architect in that he was competent in designing in both the picturesque style of Tudor Gothic (such as at Beaufront Castle and Jesmond Towers) and the classical style of the Greek Revival – and it was in the latter that he truly excelled. Although Howard Colvin praises his careful siting of the houses, high-quality finish and precise and scholarly detailing, he thought Dobson had a tendency to exaggerate the scaling, creating an overall look which might be considered bleak. Yet, this is more an academic criticism; those today looking on the many houses he worked on would consider them to be handsome examples of the flourishing of the country house which resulted from the new wealth in the north east.

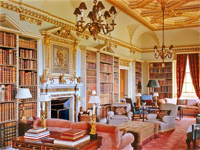

Meldon Park was to be one of Dobson’s finest of his Greek Revival designs. Built in 1832 for Isaac Cookson, at a cost of £7,188 1s 1d (about £5m today if compared with average earnings), it was a sizeable house with extensive service accommodation and extending to a beautiful Orangery, even if the main house was comparatively small. That said, the rooms are bright and well-proportioned with a grand Imperial central staircase, with its deep coffered ceiling described by Pevsner as being ‘the size of one in a London club‘. The staircase was later reworked by no lesser figure than Sir Edwin Lutyens, who replaced the original metal balustrades with wooden ones and added decorative plaster panels.

Isaac Cookson was the third generation to manage the family manufacturing interests and had taken charge of his father’s glass works, developing them into one of the country’s leading makers, along with a very successful chemical works.

Cookson had previously employed Dobson to design part of a speculative urban development in Newcastle and combined with his earlier country house work at neighbouring Mitford Hall, Longhirst (with its striking entrance portico) and Nunnykirk halls, Dobson was a natural choice when looking to create his refined country seat.

As owners of a glass works, it was natural that the house would be well-lit; the bright interior a result of the large windows which graced the main rooms on the south and east sides. Yet, Meldon Park actually marks a turning point. The brilliant Mark Girouard, writing in Country Life in 1966, pointed out that:

In rooms like this, one realises just how much Georgian architecture developed in the course of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, as windows grew bigger and more and more effort was made to link the inside of the house visually with the landscape. Meldon shows the development at its final stage; soon a reaction was to begin and the Victorians turned away from the sun and immersed themselves in increasing gloom. In this as in other aspects Meldon represents in a very convincing way, the last flowering of the Georgian country house tradition.

So Meldon Park represents not only the work of one of the finest architects to have worked in the north east but also marks a key point in the development of British architecture; the high-water mark of Georgian elegance before the more insular and muscular Victorian style swept over the north of England. The house is also one of those rare survivals where it is still owned and lived in by descendants of the person who commissioned it, sitting in its own huge estate. This is a house which seems to be clearly loved by the owners who have worked incredibly hard to ensure they can remain there especially when the house is less of an attraction for visitors as previous generations had sold the art collection. Judging by their new website and other news stories about their expanded and diversified activities it seems that they were also willing to listen to Simon Davis’ advice and act on it and such pragmatism can only be applauded and will hopefully be rewarded.

——————————————————————————

Official website: ‘Meldon Park‘

Photos from Country Life: Meldon Park [Country Life Picture Library]

Listed building description: ‘Meldon Park, Northumberland‘ [British Listed Buildings]

Want to stay there? Meldon Park: East Wing Apartment

Country House Rescue – Series 4 [Channel 4]

Country House Rescue – Episode 5 [Channel 4]

For more information about the architect: ‘John Dobson 1787-1865: Architect of the North East‘ – Thomas Faulkner & Andrew Greg