One of the finest skills an architect can possess and cultivate is that of charm; the art of turning an encounter into an acquaintance into a client – and sometimes even a friend. Such a skill can offer a balance to such flaws as he may have, whilst also being his most effective sales technique. One such architect was Philip Tilden, a man whose own assessment of his talent and skills usually surpassed that bestowed by his peers. Yet, Tilden was a sensitive man, attuned to how people wished to live in their houses and who developed a rapport within high society leading to an almost bewildering array of commissions; from the most domestic to the breathtakingly grandiose and who, along the way, managed to design houses for two UK Prime Ministers.

Philip Tilden (b.1887 – d.1956) was an avowed traditionalist. His memoirs – ‘True Remembrances‘ (though others doubt this!) – which were published in 1954, are full of repeated laments of lost skills, modern taste, and the lack of style. Not that he was ‘anti’ modern materials, but more that he thought they should be used cautiously and subserviently to the traditional ones, saying “Instead of absorbing the new materials and techniques into the body of tradition, and digesting them, we have let them take control“. His was a world where architecture was national (and hence the international Bauhaus would have been an anathema) and, for him, ‘…Britain was not the home of the acanthus and cypress – it is the home of the Gothic rose, the oak, the ash, and the parasitic ivy‘.

Though he made clear his emotional preference for the Gothic, it was part of a broader love of the ancient, in particular, of the old castles which he was called upon to restore – though circumstances would ensure that he would work with whichever building he was called to look at. Tilden was a good architect – but not a great one. Sir Edwin Lutyens, who was his contemporary but not his peer, once complained having seen Tilden’s additions to a house as ‘work so ill-conceived by a man who claims a following and dares to criticise‘. But such criticism shouldn’t obscure Tilden’s more positive characteristics; his sympathy for historic fabric, his imagination, and his consummate networking skills.

The early part of the 20th-century was still an age where patronage was in the hands of the upper echelons of society. If one could gain a foothold, the power of the related and intertwined networks of politics, business, and industry could provide a welter of opportunities for someone who could play the game. Tilden was a master of this – his memoirs are an almost embarrassingly giddy series of anecdotes of he and his wife staying with Sir ——— or Lady ———-, and the delight the hosts and visitors apparently took in each others company. It was through these connections which provided Tilden with his commissions – from the smallest artistic endeavours to the excessive.

He joined the Architectural Association in 1905 and on graduating became an articled pupil to Thomas Edward Collcutt, whom he later went into partnership with, before establishing his own practice in 1917. One of his first clients was Sir Martin Conway, 1st Baron Allington, the mountaineer, politician and art critic who once said “I have always liked the work of Mr Philip Tilden, but if anyone asks me why, I cannot fully say“. Sir Martin and his much wealthier wife, Katrina, had discovered Allington Castle, Kent and both exclaimed ‘Of course we must have it!‘ and she had bought it in 1905. Some restoration work had been carried out before 1914, by W.D. Caroe, to make the ruined castle habitable but Tilden was brought in for further changes in 1918 and became firm friends with the Conways, working on the castle until 1932.

It was this long period of friendship which enabled Tilden to extend his circle of useful connections. One of these was Sir Louis Mallet, once our Ambassador to Turkey, who had led a cultivated and international life which had created a prized social circle. It was through him that Tilden came to know and work with the wealthy Sir Philip Sassoon, the noted politician and art collector. Sassoon was a renowned host and his architectural requirements were driven by this. Herbert Baker had built the Cape Dutch-style Port Lympne for Sassoon in 1913/14 and when Sassoon wished to enhance Port Lympne after WWI, he called on Tilden. With the confidence of wealth (related as he was to the Rothschilds), Sassoon gave full rein to his artistic and stylistic preferences which were far removed from the chaste reserve of the traditional English country house. With dining room walls painted in lapis lazuli blue and lined with golden chairs and an opalescent ceiling, a Spanish courtyard, and a grand flight of steps in the garden, this was a house for show.

Yet, barely had the works on Port Lympne been completed, when Sassoon bought Trent Park, in north London, in 1923, which was to become the centre of his social entertaining. In contrast to the exuberance of his Kentish seaside retreat, Sassoon looked to Tilden to create a more traditional environment, one of lithographs and wallpaper, antiques and books. This suited Tilden who created a hugely successful pleasure palace:

“…a dream of another world – the white-coated footmen serving endless courses of rich but delicious food, the Duke of York coming in from golf… Winston Churchill arguing over the teacups with George Bernard Shaw, Lord Balfour dozing in an armchair, Rex Whistler absorbed in his painting… while Philip himself flitted from group to group, an alert, watchful, influential but unobtrusive stage director – all set against a background of mingled luxury, simplicity and informality, brilliantly contrived…“. (Robert Boothby. I Fight to Live (1947)

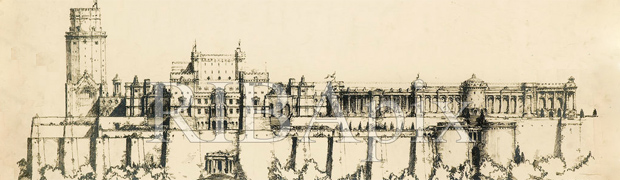

Tilden was happy to mix in these circles, both for the pleasure they brought and the commissions. In 1919, Martin Conway and Tilden were at Allington when Conway burst out, ‘You know, Philip, Selfridge is going to build a castle‘. Of course, the ‘Selfridge’ was Gordon of the eponymous department store, who had enormous plans which almost matched his ego, but which certainly outstripped his finances. We have previously looked at Selfridges’ fascinating plans in an earlier post (‘Harry Gordon Selfridge and his grand plans: Hengistbury Head‘) so no need to go into depth again but suffice to say that the whole episode showed that whilst Tilden could think big, he sometimes lacked the ability to tell his clients the honest truth about the prospects of being able to bring such grandiose schemes as Hengistbury Head or the Selfridges Tower into reality.

More successfully, Tilden was to create a home for a Prime Minister – but this isn’t about Chartwell. The first PM Tilden worked for was David Lloyd George, the controversial Welsh Liberal, best known as the founder of the welfare state, who had met the architect at Port Lympne. Lloyd George had decided in the summer of 1920 to purchase a plot of land in Churt, Surrey, where he could have a house built and gardens to tend. The area he chose was, in fact, wind-swept hillside but compensated by the views.

The house was to be called ‘Bron-y-de’, Welsh for ‘facing south’, which was a joke as the house faced north, even though he had bought the estate unseen at auction on the recommendation of his secretary who had assured him it faced south. In keeping with his character, it was a modest sized house – though one room had to be the same size as the Cabinet Room in Downing Street so that his habit of pacing could continue at the same length. Lloyd George was always in a hurry, and so Tilden designed the house so that only the ground floor was brick to reduce the drying time, with a huge mansard roof covering the first floor. Once word was out that the house was to be built, Tilden was deluged with offers of free fittings and materials, however, Lloyd George was a deeply scrupulous man who gave strict instructions that everything down to the last nail was to be paid for. Despite his modesty, it became apparent that the house was too small, and so Tilden was again employed in 1921 & 1922 to extend the house. Sadly, Bron-y-De burnt down in 1968.

Of course, the house Tilden is best known for is Chartwell (subject of the earlier guest article ‘Sir Winston Churchill, Chartwell, and Philip Tilden’ – National Trust ‘Uncovered’‘). Another commission as a result of a long fireside chat at Port Lympne, Churchill asked Tilden to help adapt the Victorian home to his requirements. The chapter in Tilden’s memoirs about the project is almost more an encomium to his client, lavishing praise on all aspects of his life and his interest in Chartwell; ‘No client that I have ever had, considering his well-filled life, has ever spent more time, trouble, or interest in the making of his home than did Mr Churchill‘. The house which resulted is certainly more practical than beautiful – though it achieves the original goal of allowing the undeniable pleasure of the superb views.

Sassoon and his circle of friends was to bring work at other country houses such as Easton Lodge, Essex, Hill Hall, Essex, Saltwood Castle, Kent, Luscombe Castle, Devon, and Anthony House, Cornwall. Of all the works Tilden deserves credit for, for me, his rescue of Dunsland House is perhaps the most admirable and the saddest. Dunsland was one of the oldest houses in north Devon and had been owned by the Bickford family who had created a home with some of the most remarkable plasterwork to be found in the county. Having owned the house for over 300 years it was finally sold in 1945 to a timber merchant who was interested only in the trees.

In 1949, Tilden was sent by the council to inspect the now seriously ‘at risk’ house. Realising that no-one else would be taking on the restoration, Tilden stepped up and bought it – and paid the timber merchant £5 for every tree he spared. Using his own limited funds, Tilden brought a small section of the house back to a habitable state and moved in, but the project proved too much and he died in 1956. His actions had staved off the immediate threat of complete collapse and the National Trust took over, finishing the restoration. Sadly, in November 1967, just as the house was ready to open to the public, a fire broke out and completely destroyed it.

A sad loss of not only the house, but also what would have been a fitting reminder of one architect’s love of the ancient fabric of the nation’s built heritage; one who romantically thought that, ‘Most of those who build are interested in what has gone before, and their aim and object is to find out how to restore the present to something like a period that they imagine to be ‘a land where it is always afternoon‘.’ Tilden today is perhaps best remembered for what he didn’t build for Gordon Selfridge and the unexciting work at Chartwell, but he was certainly a principled and thoughtful architect whose views on heritage many would respect today.

———————————————————-

There is a fine selection of images of Port Lympne in the Country Life Picture Library

Further reading:

- ‘True Remembrances; the memoirs of an architect‘ – Philip Tilden (1954, Country Life Ltd)

- ‘Lush and Luxurious. The Life and Work of Philip Tilden 1887-1956‘ – James Bettley (1987, RIBA)

- ‘Twentieth Century Castles in Britain‘ – Amicia de Moubray