Many of the houses featured in this blog are shown as a celebration of the brilliance of our architects and craftsmen in creating one of the finest bodies of buildings of their type in the world. Yet, in abundance is, perhaps inevitably, failure; where an interesting house becomes a victim of circumstance, policy, incompetence or, sometimes, all of the above. Great Barr Hall, once outside Birmingham, now encircled by advancing urbanisation, is a sad example of where a house can languish and deteriorate whilst deliberate vandalism and institutional lethargy condemn it to its fate – and unless something is done soon, Great Barr Hall will join the already far-too-long list of the lost country houses of England.

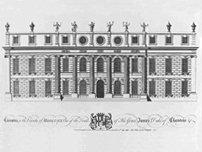

Despite its current sorry state, Great Barr Hall was once a sizable house – though precisely how large is unclear. An early print in 1798 Stebbing Shaw’s ‘History and Antiquities of Staffordshire‘ shows a 11-bay castellated house with four corner turrets but the present house is 9-bays. For comparison, it’s interesting to note the stylistic similarities with Syon House in west London, a seat of the Dukes of Northumberland, though it is also 9-bays wide and has an imposing porte cochere.

What is known is in the 1760s, Sir Joseph Scott, then head of a family line which had been in the area for 600 years, built a new house in a ‘gothick’ style. The original architect is unknown but Stebbing Shaw describes how ‘The present possessor [Joseph Scott], about the year 1767, began to exercise his well known taste and ingenuity upon the old fabric, giving it the pleasing monastic appearance it now exhibits – and has since much improved it by the addition of a spacious dining room at the east end, and other rooms and conveniences‘. If Scott was his own architect, perhaps he was, in part, inspired by the remodelling of Syon House by Robert Adam which started in that same year.

Sir Joseph Scott’s original extensive works led to some financial difficulties and so, from 1785, he moved to the Continent and rented the house out. The lease was taken by Samual Galton junior, a controversial Birmingham Quaker, banker, gun manufacturer, and intellectual who hosted meetings of the Lunar Society at Great Barr Hall leading to it becoming a noted crossroads for industrial ideas, a crucible for the Midlands industrial growth and the wider Industrial Revolution.

Where Great Barr becomes particularly interesting from our point of view is with the arrival of the young architect John Nash and his business collaborator and famous landscaper, Humphrey Repton. Nash was there to provide the buildings which Repton needed to complete his gardening visions. This worked well for both men; Nash was to pay Repton 2.5% for any work the latter passed his way so Nash charged his clients the then rather high fee of 7%, giving him a 4.5% fee. There is no record of Nash ever putting any work towards Repton – but Nash benefited with work on over one hundred estates. There seems to be some uncertainty as to exactly when Nash started working there but John Summerson gives the date as 1800 for the construction of a gothic archway to the adjacent chapel, but other works such as the gate lodges, an icehouse and a new steeple for the chapel started in 1797 and were probably also by Nash and Repton.

About this time, the house was also updated to create the appearance we can just make out today – but it hasn’t been confirmed that Nash was the architect. However, there are tantalising clues that it could well be by him. Nash had been developing his particular style of Picturesque gothic during his time in Wales and had been applying it with varying degrees of success since then during alterations at Kentchurch Court, Herefordshire, (1795) and at Corsham House, Wiltshire (1797 – a disaster due to poor workmanship with Nash’s work later demolished). Yet, some of the architectural fingerprints of each of these can be seen in Great Barr. Externally, one such feature is the crenellations applied to both the roof and the tops of the projecting towers, another is the hooded Elizabethan-style windows. Another interesting piece of the jigsaw is a house which Nash was working on in 1800 in Buckinghamshire, Chalfont Park, which bears not only a superficial stylistic similarity but also one of form – a long rectangular main body with a projecting 3-bay centre. However, Chalfont Park was also altered by Anthony Salvin in 1840 so it’s not possible to tell how much of the gothic detailing is Nash’s.

The Scott’s return in 1797 prompted the works of Repton and Nash before further work in 1830 and 1848 which included moving the entrance from the west side to the north. In 1863, a chapel was built to a design thought to be by Sir George Gilbert Scott, though it was never consecrated and so became a billiard room.

The house remained with the Scotts until the house became a hospital for the mentally ill in 1918 following the death of Lady Bateman-Scott in 1909. As is usual, the institutional nature of hospital use was not kind to the house. Beyond the extensive network of buildings which marched across Repton’s parkland (and the south eastern corner of the estate being carved up by the M6 motorway), the house itself had a modern two-storey extension added in 1925 and in 1955 the clock tower, stables and much of the east wing were demolished. In the 1960s, some sensitive architectural ‘genius’ removed the two splendid first-floor oriel windows which flanked the main entrance and inserted a pair of non-matching government-issue casement windows.

The current plight of Great Barr Hall can largely be laid at the door of Bovis Homes and John Prescott, formerly the Deputy Prime Minister, and the one who eventually signed off on the architectural blight that now affects the house. Considering that the hospital buildings were in two distinct campuses, one to the north west and another to the north east, if there had to be development, replacing the buildings to the NW would have placed them furthest from the house, with the advantage of creating a more complete parkland around the house, with the possibility of re-instating, to some extent, the earlier Picturesque drive. To hope that someone of Prescott’s aesthetic insensibilities would see such a solution was always forlorn but one might hope that someone on the local council or in English Heritage might have proposed a more sensitive outcome. Sadly it was not to be and now a large development of 445 executive-style homes has been built, the closest being scarcely a hundred metres from the back of the house. Worse, following the sale of the house to a building preservation trust, little progress has been made, with questions now being asked about the trust’s failure to restore it as promised earlier. It was again put up for sale in May 2011 by the Trust at the unrealistic price of £2.2m with the option to buy a further 100-acres of parkland – with the threat of even more development.

Despite some architectural uncertainties, what is clear is that those charged with its care in the recent decades have failed. Perhaps this is a broader failure of policy, that without an explicit mandate to determine that the architectural heritage must be managed, maintained and preserved as far as is possible, it will fall to all-to-fallible councillors to look beyond their own short-term interests; sadly, an unlikely prospect. The NHS generally has a poor record of managing historical assets once it has no further use for them e.g Sandhill Park, and Stallington Hall are just two examples and don’t forget that Soane’s Moggerhanger survived despite the NHS, not because of it. A strong national policy should provide a clear strategy for preservation of heritage assets taken over by the state rather than just relying on existing listed buildings legislation. In Great Barr Hall’s sad circumstance, one can only hope that someone will be able to extract the money owed as part of the enabling development, which can then be devoted to restoring this interesting and significant house so that it once again can be something for the local residents to be proud of, rather than the monument to NHS, central government and local council incompetence which it is today.

————————————————————————

Still for sale? (thanks to Andrew for spotting this): Great Barr Hall might still be for sale – there is a page with details but it’s not listed on the agent’s website: ‘Great Barr Hall‘. Now listed for £3m but with 150-acres but with another 100-acres of parkland by separate negotiation. Considering the Building Preservation Trust paid just £900,000 for the entire site this seems a little odd – perhaps someone will enlighten us.

————————————————————————

Listing description: ‘Great Barr Hall‘ [British Listed Buildings]

‘At Risk’ Register entry: ‘Great Barr Hall‘ [English Heritage]

Recent history of house and some proposals for rescue

News stories:

- ‘Fears grow for future of Great Barr Hall‘ [Birmingham Mail]

- ‘£2.2m price tag for Great Barr Hall‘ [Express & Star]

- ‘18th century Great Barr Hall put up for sale‘ [Birmingham Post]