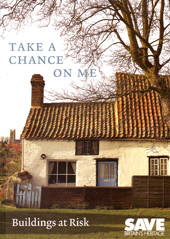

Despite the obvious deep and passionate interest society has with historic buildings every year the SAVE Britain’s Heritage Buildings at Risk Register highlights just how many properties are still under threat from neglect and those in power who believe the only good building is a new one with their name on the opening ceremony plaque. The 2011 BaR register – ‘Take a Chance on Me‘ – has just been published and sadly, as always, it contains some country houses which really deserve a better fate.

Perhaps the one of the most attractive, both architecturally and in terms of being a case for restoration is Blackborough Hall, near Cullompton in Devon. This elegant, if thoroughly dilapidated grade-II house, is a remnant of the grand building plans of the Earl of Egremont whose many-columned main house, Silverton Park, was demolished in 1902. The house is actually two, as when built in 1838, it formed one house at the front and a second at the rear for the local rector. In recent years it became a car scrap yard which covers most of the immediate grounds and would obviously need clearing first – though I suspect the costs could be made back through selling some of the classic cars. The house is currently for sale for a nice round £1m and has been listed with Winkworths who, after an initially poor showing, have now managed to put a few more photos and a floor-plan online.

Elvaston Castle in Derbyshire has a grade-II* listing putting it in the top 4% of buildings nationally but that hasn’t stopped it making an entry into the Register this year. Originally built in 1633 for the Earls of Harrington it was largely rebuilt in a ‘Gothick’ style c.1817 to designs by James Wyatt. Now owned and managed by Derbyshire County Council (who had a fairly poor record in the 20th-century of demolishing country houses in their ‘care’) it is today mostly vacant and with the Council now claiming it can’t afford to maintain it they are seeking a developer to get them out of a hole of their own making. Luckily an active local campaigning group – the Friends of Elvaston Castle – have been objecting to these plans and trying to force the Council to face up to their responsibilities – though perhaps there is an opportunity for someone else to come up with a viable plan.

Stone Cross Mansion, Cumbria presents the interesting confusion of a Scots Baronial design in England. Built in the 1870s by a stubborn man, one Myles Kennedy, who wanted to buy Conishead Priory for £30,000, but who met an equally stubborn vendor who wouldn’t accept less than £35,000. Mr Kennedy may have come to regret his obstinacy when presented with the final bill which totalled nearly £45,000. The sum reflected the high quality of the workmanship, particularly the impressive High Victorian Gothic grand hall (scroll down) which originally had a fine staircase which was later removed when the house became a special school to make it easier to play indoor football (seriously, where do they find these people?!). The house then became a corporate headquarters during which it time it was restored to a high-standard before falling into neglect. Repeated enabling development proposals have been rejected (not that the council is against it) so this house either needs someone willing to restore the house on the back of a sensitive ED proposal – or, ideally, someone to rescue this house and make it a home again.

Another house which would make a fantastic home is Plas Gwynfryn in south Wales. This house has been featured before on this blog (‘Orphan seeks new carers: Plas Gwynfryn, Gwynedd‘) which sparked some passionate debate in the comments about who the owner is – and that same unresolved question is why the house makes an appearance in the BaR this year. Built in 1866 to replace an earlier one, this distinctive house – described in the listing description as ‘romantically assymetrical’ – was a hospital in WWII, before becoming an orphanage and then a hotel before a serious fire in 1982 gutted it. Although in a derelict condition this house can be restored and would once again be a fine part of the local architectural heritage.

The Register is available from 1 June 2011 priced at £15 (£13 to Friends of SAVE) and can be ordered from the SAVE website. The BaR contains many other types of property so even if your budgets are less lavish than these house might require it is well worth having a look. Of course, SAVE does superb work across the country to protect our architectural heritage and I would strongly urge everyone to become a Friend to help support their efforts (well, I would say that as I’m on the Committee – but I’d also say it anyway!) which will also give you access to the online version of the BaR register which contains hundreds of other potential future success stories.

——————————————————————————–

A more comprehensive list of country houses currently at risk can be found on my Lost Heritage website: ‘Houses at Risk‘